The green bond market is flourishing, but there is plenty of room for further growth. In this article, we look at the development of the market and explore why corporates should consider issuing green bonds.

In his outgoing address, former US President Barack Obama said: “We’ve led the world to an agreement [the Paris Accords] that has the promise to save this planet. But without bolder action, our children won’t have time to debate the existence of climate change. They’ll be busy dealing with its effects. More environmental disasters, more economic disruptions, waves of climate refugees seeking sanctuary.”

Climate change is arguably one of the great issues of our time. And to prevent further environmental damage, significant investment is needed in environmentally friendly projects. Governments around the world have reacted to this need and have committed substantial amounts to green projects. However, this is significantly less than the US$10.5trn of green investment that the International Energy Authority estimate is required in the coming two decades to halt climate change.

Shades of green

Channelling the tens of trillions of dollars that exist in the capital market towards climate change solutions is an effective way to achieve this. And core to this is the green bond, a financing product that can be loosely defined as any bond where the proceeds are specifically earmarked for green or environmental purposes.

In an effort to tighten the definition of a green bond, the International Capital Markets Association (ICMA) has created a set of Green Bond Principles (GBPs) – a voluntary framework that looks to add some structure to the green bond market. According to Nicholas Pfaff, Secretary of the GBPs at ICMA, companies that issue green bonds can publicise to investors that they are green by posting them on ICMA’s website and adhering to four key principles:

- The use of proceeds must be put towards projects that provide environmental benefit.

- There must be a clear process to determine how the project fits within the eligible Green Projects categories.

- Proceeds must be segmented and tracked so investors can ensure their money has been used towards green projects.

- A framework must be put in place to show how the company will evaluate and report the impact of the project on the environment.

However, there are some nuances that need to be addressed because not every bond that is green is labelled a green bond. Indeed, statistics from the Climate Bonds Initiative highlight that only 17% of their broader definition of ‘climate aligned bonds’ are labelled green bonds. Sean Kidney, CEO of the Climate Bonds Initiative, explains that a bond issued by a solar wind farm company should be considered green even if it does not register with the GBPs, for instance.

“Ideally companies would abide by the GBPs,” he says. “Investors have expressed that this helps when they are reporting back to their clients and we believe that labelling is key to the overall growth of the market. However, it is important not to get caught up too much in the semantics as this can often detract from what we are all trying to achieve here.”

Click to englarge

On the flip side, there is a lot of debate about whether labelled green bonds from traditionally non-green issuers should be considered truly green. In recent months, this debate has been reignited by the green bond issuance by Spanish oil giant Repsol and the first ever sovereign green bond issued by Poland. The Financial Times reported that some investors passed on investing in these bonds because one was from an oil company and the other from a country that was also raising finance for new coal plants as well as green projects.

ICMA’s Pfaff believes that investors criticising such issues on that basis are missing the point slightly. “The green bond market is meant to promote the transition of business models towards being greener and sustainable,” he says. “You can therefore have non-green businesses issue bonds focused on green projects and these bonds will still be classified as green under the GBPs.”

Exceptional growth

Definitional issues aside, the green bond market has grown markedly since the first issuances by the European Investment Bank and World Bank in 2007. However, in those early years, progress was slow and dominated by multilateral agency issuers. It wasn’t really until the GBPs were first published in 2014 that the market began to take off and corporates began to enter the market, with issuance rising to just over US$11bn that year, up from US$3.1bn in 2013.

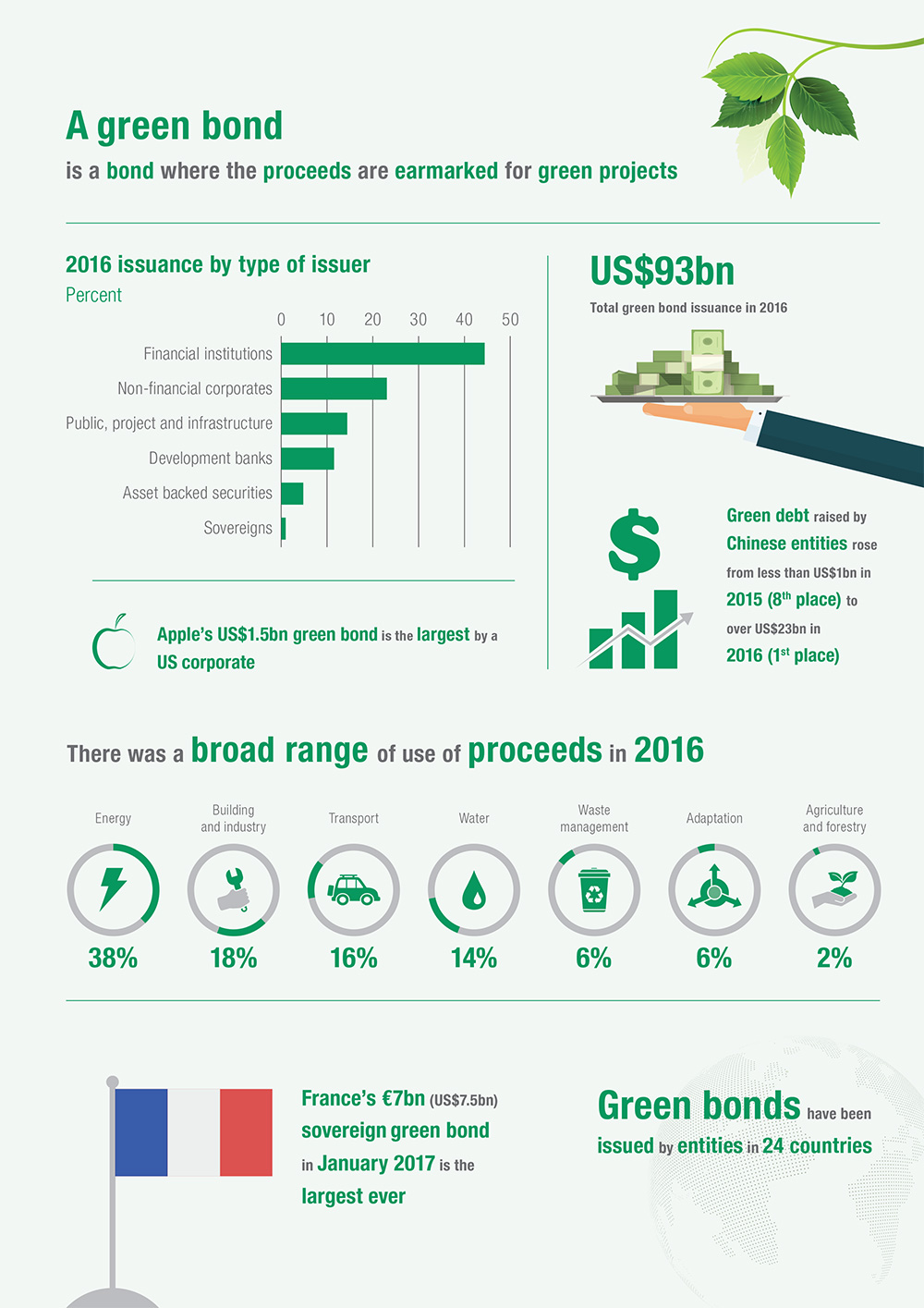

Recent growth has been more dramatic. Indeed, 2016 saw US$93bn of green bonds issued, including domestic Chinese green bonds, a record year and a greater than 100% increase compared to 2015. “All eyes have been on the green bond market in the past 12 to 18 months,” explains Beijia Ma, Equity Strategist at Bank of America Merrill Lynch (BofAML). “The market has really begun to take off and this is being driven by China, which is now the world’s biggest green bond market.”

If we are to shift our economies at the speed and scale needed to stop the planet becoming uninhabitable in the second half of this century then we need to give it everything we have. This is about survival.

Sean Kidney, CEO, Climate Bonds Initiative

Ma is keen to note that while all eyes are on China, other emerging market countries are also developing green bond markets. “Europe is the most developed market,” she says. “But we can’t overlook the progress being made by the ASEAN countries, India and Brazil where the governments are taking active steps to develop and promote the market.”

Geraint Thomas, Executive Director at MUFG, is also buoyed by the evolution of the green bond structures being used by corporates. “In the last few quarters we have seen the first hybrid structure issued by TenneT. Toyota in the US also completed an asset-backed security deal a few years back,” he says. “These are important developments and I believe in the coming years we will see securitisation grow, with all the other bond structures that we are used to turning green as well.”

Growth in the market is also being driven by investors hungry for green paper. “We have seen significant growth in the amount of money that investors are dedicating to green and ESG investments,” says Thomas. “This has been the other significant driver behind the market and demand is still outstripping supply.”

What is in it for corporates?

Attracting new investors is precisely the reason why many corporates have issued green bonds. As the Climate Bonds Initiative’s Kidney explains: “The number one reason that corporates issue green bonds is to diversify their investor base. They have realised that there is a huge pool of people (and money) that like to invest in green products, many of whom they might not have dealt with before.” Kidney adds that corporate treasurers have told him that if they are able to get 15-30% of new investors to register for the bond then that is a huge success and will lead to price depreciation in the future.

Kidney is also keen to add that issuing green bonds creates an investor ‘stickiness’ for corporations. “Investors are calling for corporates to do more green bonds and they are genuinely enthusiastic about buying green paper,” he says. “This is a dream scenario for corporate treasurers issuing bonds.”

Off the back of this huge demand and diversified investor base, corporates are also beginning to realise price advantages by issuing green bonds, says Kidney. “Like any market, as it gets larger, prices begin to depress,” he explains. “Issuers are now realising a five to 15 basis point benefit in the dollar and euro green bond markets over traditional bond markets. This is great news and it will boost issuance next year.”

Elsewhere, BofAML’s Ma notes that there is a marketing benefit to be had from issuing green bonds. “Issuing a green bond can raise a corporate’s overall sustainability profile,” she says. “Apple, for instance, used its green bond last year to highlight all the work it is doing making sure its factories use renewable energy.” Meanwhile, ratings agencies like Moody’s and S&P are actively exploring how CSR commitments might factor into a company’s overall credit rating.

Straight to market

If these benefits are not enough, treasurers will be pleased to hear that the process of issuing a green bond is not too dissimilar to that of issuing a traditional bond, although there is some extra work required when making the first issuance.

“The bond structure and the terms and conditions will be very similar to a non-green version of the bond,” says MUFG’s Thomas. “The lead-up to issuance, however, is slightly different, beginning with the internal process for identifying the use of proceeds and ensuring this fits into the investors understanding of what is green.” Thomas notes that the issuing team will then need to work to make sure the bond aligns with the GBPs if it is to be labelled. “They may wish to get a second or third opinion on this to further verify the bond. This can, of course, add incremental cost to the first issue,” he adds.

To encourage corporates to issue green bonds, some countries are looking to remove this incremental cost. For instance, the Monetary Authority of Singapore announced earlier this year that it is launching a Green Bond Grant scheme which will cover the costs of external reviews for green bond issuance.

Adam Stam, Director, Secured Funding at Toyota Financial Services, worked on the company’s debut green bond issuance. He notes that while the credit risk associated with green bonds is no different from a traditional bond, there is an extra degree of reputational risk that needs to be managed. In Toyota’s case, it was necessary to ensure that the company could rapidly deploy the funds into investment in green vehicles. “It is important that any company looking to issue a green bond is aware of the reputational risk,” says Stam. “They shouldn’t just jump on the bandwagon, because in doing so they run the risk of damaging their reputation by not being able to deliver on their promises of investing in projects which are considered green.”

China’s flourishing market

To find the world’s largest green bond market you need to look towards the world’s biggest polluter, China. Almost overnight, the country went from being a minor player in the market to accounting for 40% of the total value of green bonds issued globally last year. So what has been behind this rapid rise?

China is facing some serious environmental issues. The People’s Bank of China has estimated that the country needs US$320bn a year to meet government targets for addressing widespread air, soil and water pollution. Encouraging the financing of a green economy is therefore just one part of a wider plan from the Chinese government to halt or reverse the environmental issues that the country currently faces.

But as Herry Cho, Director, Head of Sustainable Finance Asia at ING, explains, ‘greening’ the Chinese financial system is crucial if the government is to achieve its objectives. Indeed, China’s 13th Five-Year Economic Plan states the importance of a “green, open and shared” development and incorporates a strategy for establishing a green financial system into the National Ecological Civilisation Construction Plan.

On the world stage China has also become a leader in the field. “As the G20 Chair, China has really put sustainability right at the forefront of the agenda and is encouraging the rest of the world to follow in its footsteps,” says Cho.

Nuanced ‘green’

It must be noted that while China is taking great strides in the green bond space, it is slightly unique in terms of what it qualifies as green. “Despite largely being based around the GBPs, China does have slightly more broader standards around what qualifies as green,” says Cho. “This is perhaps most evident around the fact that China permits green bond proceeds to be put towards so-called clean coal projects.”

Another nuance is that in other countries all proceeds from a green bond go towards green projects. In China, however, corporate borrowers may use up to half of the proceeds of the bonds for working capital and paying down loans.

To offer some statistics, the latest numbers from the Climate Bonds Initiative show that 61% of the US$2.47bn in green bonds issued by China in the first quarter of this year failed to meet the international definition of such instruments.

With the country slowly liberalising its bond market and looking to attract outside investment, more transparency and a greater adherence to international standards may be needed before international green investors feel fully comfortable investing in Chinese green bonds.

That being said, the future looks bright for China’s green bond market and Bloomberg Business estimates that by the turn of the decade China’s green bond market could be worth US$230bn.

Green shoots

The green bond market, at the time of writing, is on course for another impressive year. However, despite the recent growth these bonds still only make up about 1% of the total value of the world’s capital markets. There is clearly a lot of room for the market to grow, and some would argue that this growth is vital to the future of the planet. What then is needed to help the green bond grow stronger?

For BofAML’s Ma, more government support is key. “The long-term trajectory of the market is good, but in the short term government support will be vital,” she says. “Governments offering favourable rates or subsidies to green bond issuers, like we have seen in Singapore, is just one way that this can be done. This will attract more and more companies to issue and see the benefits that this can offer.”

The need for governments to offer incentives is also cited by ICMA’s Pfaff. “We see significant growth in the market again this year and that is encouraging,” he says. “But for the market to expand at the rate we need it to, and for it to reach new markets, governments should also consider intelligent incentives to encourage especially corporates to issue green bonds.”

For ING’s Cho, the need isn’t just around more issuers coming to market; it is about ensuring that there are enough bankable green projects, especially in the emerging markets. “It is crystal clear that the amount of funding that is required for sustainable development is huge,” she says. “But the key issue that needs to be solved in Asia and other emerging markets is making sure that there is a pipeline of bankable projects available to finance.”

MUFG’s Thomas agrees and would like to see smaller companies embracing the green bond market. “The biggest constraint to its further development is size,” says Thomas. “Most investors are looking for bonds that meet the benchmark liquidity size. Most medium and small enterprises probably do not have green projects that fall into that category so they will struggle when issuing. It is here that securitisation can be an effective tool to grow the market.”

The Climate Bond Initiative’s Kidney believes that it is vital that the whole financial system comes together to make this market grow. “The market is far too small at present and not flourishing enough in my opinion,” he says. “If we are to shift our economies at the speed and scale needed to stop the planet becoming uninhabitable in the second half of this century then we need to give it everything we have. This is about survival.”