Listening is an integral part of life. From listening to your loved ones at home, to your colleagues in the office, you can’t get far without it. Treasury Today spoke to experts about the importance of listening, what it means for treasurers, and how you can improve your skills.

The Treasury Recruitment Company recently conducted a study and used the data to compile “The Treasury Skills Wheel”, a selection of skills that every treasury professional should master. Soft skills such as communication and relationship building feature heavily. Indeed, soft skills are increasingly being recognised as important in the workplace – especially as treasury has become much more integrated with core teams and functions of the business.

Laura White, Operations Director, The Treasury Recruitment Company, says: “As treasury has become more valued and recognised across businesses from an operational perspective, we have noticed a significant shift in the importance hiring managers are placing on certain soft skills when making hiring decisions. These are no longer viewed as ‘a nice to have’ but an essential requirement, often ranking at the very top of the ‘must have’ list of skills.”

White adds that effective communication and relationship-building skills are of particular importance, “as it is no longer just about treasurers talking to other treasurers or finance partners, but often about being able to articulate complex situations and problems to non-finance people, many of whom do not even have a base level understanding of the subject.”

A key skill that underpins all communication is the art of listening, but in practice this means something different to everyone. To some, it may simply mean the basic process of hearing what someone else is saying. To others – and many experts agree – hearing and listening are two separate things. It’s also important to understand the different types of listening that people can do.

Whatever your belief about it, listening is one of the most important skills any person – professional or not – can have, and yet research from ‘Business Communication: Strategies and Skills’ by R. C. Husman, J. M. Lahiff and J. M. Penrose (1988), has shown that the average person’s listening is at only 25% efficiency.

Listening matters

Julian Treasure, a sound and communication expert and founder of The Sound Agency, and Richard Mullender, an ex-Metropolitan police hostage negotiator, both rank listening at the top of the list of necessary traits for both managers and staff.

Mullender states that listening is the most important aspect of communication. “You’ll never understand someone by talking to them – you’ll only ever understand them by listening to them,” he says.

“It’s important to understand that listening and speaking are related to each other – it’s a circular relationship,” says Treasure. “It’s impossible to inspire people if you don’t understand them, and listening is always the doorway to understanding.” Treasure defines the four styles of leadership as “tell, sell, consult, join,” and notes that three out of the four require listening skills.

Leaders who listen

Key to any manager’s position, treasury or not, is the ability to influence and lead their team. “Listen, understand, influence,” says Mullender. “If you listen to a person, you can understand them. If you understand them, you can influence them.”

Sonia Clifton-Bligh, Director, Regional Treasury Services Centre Asia Pacific, Johnson & Johnson, notes that when an individual first steps into a leadership position there is a “tendency to believe you have to speak with confidence and authority, and be armed with all the answers.” As she has progressed in her career, however, she is “now more concerned with communicating to inspire, engage, encourage dialogue and idea generation.”

She believes that a leader’s objective should be to ensure that the team feels empowered, trusted, and respected, and that providing an open and inclusive communication style is integral to this.

“Listening is the primary warning sense for a reason,” comments Treasure, highlighting the importance of listening for threats, opportunities and ideas, as well as the role listening plays in the learning process. “It’s probably the most important skill to develop in order to be a good leader or a good worker – and yet we don’t teach or prioritise it, so most individuals and almost all organisations are very poor listeners,” he adds, citing The Organisational Listening Project’s findings that organisations that are better at listening have better work environments and results.

Non-verbal communication

In the 1970s, Professor Albert Mehrabian of the University of California studied the relevance of verbal and non-verbal messages during communication. He found that if a speaker’s words and body language – in other words, their verbal and non-verbal messages – differed, the listener was more likely to believe the nonverbal communication than the verbal.

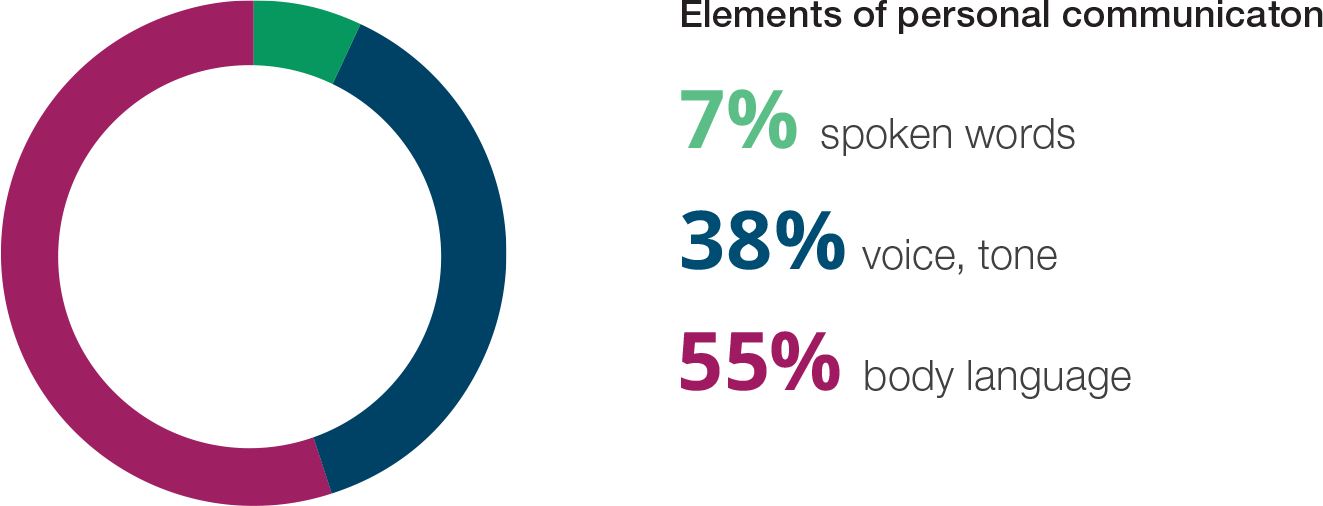

Professor Mehrabian then split communication into three distinct sections: words, tone of voice, and body language. He concluded that words account for only 7% of communication, tone of voice for 38%, and body language for 55%. Although the accuracy of Mehrabian’s quantification of communication is disputed – and both Treasure and Mullender disagree with it entirely – it does work to highlight the importance of nonverbal cues when communicating, and not just when listening.

Clifton-Bligh appreciates the importance of non-verbal communication as well, noting that “non-verbal communication, such as body language, gestures, pitch or tone of voice, can communicate unintended messages.” Ensuring your body language matches your message is essential to ensure that you create “an environment where people feel their voice is heard and that they won’t be judged for their contribution,” she states.

Dr. Albert Mehrabian’s 7-38-55% Rule

Source: https://www.rightattitudes.com/2008/10/04/7-38-55-rule-personal-communication

Mehrabian himself admits that his theory is limited in its applications and only applicable in certain contexts, and this has become more evident with the increasing use of technology as online messaging, emails and texts have become more widely used forms of communication.

Whilst his theory may be contested in 2019, it does suggest that if a person wants to be heard, they need to ensure that they match their words with suitable and effective tone of voice and body language.

Improving your skills

Treasure shares two of his top tips from his book, ‘How to be Heard’. The first, he says, is to give yourself a few minutes of silence each day. “Silence recalibrates the ears, resets your listening, and allows you to listen afresh,” he comments, noting that this is especially important in a world where people are surrounded by constant noise. “We can go very numb and cease to be able to listen effectively,” he says.

The second tip relates to the concept of “listening positions”. Treasure suggests that we all listen through filters. “Your filters include the culture you were born into, the language you speak, your values, attitudes, beliefs, emotions, expectations and intentions,” he states. Treasure believes that our individual listening changes throughout the day and that listening is unique for each person. If you can become conscious of those filters, you can change the way you listen.

Clifton-Bligh emphasises the importance of applying these filters when communicating with teams, believing that “it’s important to not assume that your style is understood.” She makes an active effort to ensure she doesn’t use expressions or colloquialisms that could cause confusion or be misinterpreted, and has found that this is especially important when speaking with groups from diverse backgrounds.

One of Mullender’s top tips for improving listening skills is to “give yourself an outcome and know what you’re listening for.” He suggests that when listening to someone, individuals need to pay attention to certain things: facts, emotions and motivators, to name a few. “The key to it all is understanding the person you’re talking to,” he says.

Active listening

Mullender also mentions active listening skills, noting that they aren’t quite what they seem. Active listening skills include verbal and non-verbal things that a listener can do whilst someone is talking to demonstrate attentive listening. However, as Mullender points out, “nodding your head doesn’t help you listen. Saying ‘okay’ or ‘carry on’ only keeps the person talking – it doesn’t mean you’re listening and understand what they’re saying.” And understanding is, of course, a key outcome of listening.

For Clifton-Bligh, active listening also includes noticing when things might need rephrasing to clarify ambiguous points, and to check for understanding. By paying attention to how someone is receiving your communications, and adapting accordingly, a “productive exchange of information” is encouraged.

Types of listening

Treasure identifies three types of listening: outer, inner, and created.

- He defines outer listening as “making meaning from sound” – a process that involves selecting what sound to pay attention to, and then interpreting it. This is a mental process that Treasure says differs from simply hearing.

- Inner listening, he explains, means understanding that the voice inside your head is not you; rather you are the one listening to it. Treasure says that learning it is possible to ignore this voice is a very powerful skill – especially for those with quite a negative inner voice.

- Treasure defines created listening as something that arises from the speaker’s actions and reputation, as well as from the listener’s own unique listening filters. “It changes over time and from person to person, or audience to audience,” says Treasure, “so it is a grave but very common mistake to assume that everyone listens like you do.”

Bad listening

In Mullender’s previous career as a police hostage negotiator, he had to learn not only how to be a good listener, but also what makes a bad listener. Generally, what’s the worst thing someone could do when listening to someone else?

“Not knowing what you’re listening for,” says Mullender. “If you don’t walk into a meeting knowing exactly what you want to get out of it, you won’t get anything.”

Clifton-Bligh emphasises the need to “communicate clearly and succinctly” in all situations – a skill that can be important in a range of scenarios, such as meeting and negotiating with banks, service providers and suppliers.

People that shout over others don’t tend to listen very much – and eventually they don’t get listened to either because people get fed up with not having attention paid to them.

Richard Mullender, Listening and Communication Expert, Mullender’s

Similarly, when trying to understand how another person feels, it’s important to accept the limitations to how fully this can be achieved. It’s arrogance, says Mullender, to assume you know how someone feels, even if you have had a similar experience. You can only ever understand how someone feels, not truly know for yourself – and the only way you can understand is by listening to what the other person in saying.

In a workplace setting, this application is particularly useful when speaking with a staff member who is upset or angry. Being a leader means navigating both the ups and downs of your team – and learning how to handle all situations is crucial to effective communication and overall team happiness.

Listening better

Treasure notes that his TED talk, ‘How to speak so that people want to listen’, has been viewed five times more than his talk on listening, ‘Five ways to listen better’. This emphasises the extent to which most people prioritise being heard over hearing others.

His advice for anyone struggling to be heard? “Listen better.” He says that being sensitive to how others like to receive communications will ensure you become much better at communicating effectively. “Often the problem with struggling to be heard is choosing the wrong time, or saying the wrong thing,” he comments.

According to Treasure, a key question that speakers should ask themselves in order to be good communicators is “what’s the listening I’m speaking into?” He states, “Just by asking that question, you automatically become sensitive to it.”

Mullender’s advice to someone struggling to be heard is just as simple: “Make sure what you’re saying is important to the person that’s listening to you.” In other words, it’s important to make sure that the people listening are actually interested in hearing what you have to say. Even the most charismatic speaker in the world may struggle to hold an audience’s attention unless the audience has something to gain from listening to what is said.

Mullender agrees with Treasure’s statement that in order to be listened to you need to be a good listener yourself. “People who listen well tend to be listened to,” Mullender points out. “People that shout over others don’t tend to listen very much – and eventually they don’t get listened to either because people get fed up with not having attention paid to them.”

Two-way street

So where does that leave treasury professionals? In order to lead a team effectively, treasurers need to both listen and be listened to. Similarly, team members need to be able to listen to instructions – but also speak out when the need arises.

Clifton-Bligh strongly believes that “communicating contributes to transparency and encourages trust.” She adds, “Trust is conducive to creativity, and seeing an idea come to life brings satisfaction.” After all, communication is a two-way street and both parties need to be open to hearing one another.

As Treasure points out, as a society, every day we are almost overloaded with noise. It’s natural that people try to tune out the noises that may seem to be of very little worth – but it’s also essential to avoid accidentally cutting out too much, lest we miss the important things.