Over recent years we have seen numerous examples of multinational companies making changes to their accounting methods for pension plans and other post-retirement benefits. But that is just one of the many new remedies to which treasurers are turning for relief from their pension headaches these days. In this article, we consider the challenges facing company pension plans, and the skills, knowledge and experience treasurers have to offer in overcoming these challenges.

Back in the first week of January, Ford Motor Co. announced that it would be changing how it accounts for the performance of its pension plans, a move that the company expects to provide a $1.5bn boost to its pre-tax profits for 2016.

By changing to mark-to-market (MTM) accounting, the second biggest automaker in the US will be following in the footsteps of a host of other US corporates including AT&T, UPS, Verizon Communications, FedEx, and Honeywell, whose treasury team won an Adam Smith Award after the company became the first to make the move in late 2010. Ending the longstanding practice of ‘smoothing’ large deferred gains and losses generated by changes in interest rates and actual returns on assets over several years has allowed these firms to provide a clearer picture of the underlying performance of their business operations.

The new model will mean that changes in the funded status of defined benefit (DB) pension plans, which promise to pay a specified amount to retirees, are now recognised annually as and when they occur. Companies like Honeywell say that this provides for greater transparency in earnings reporting. “I think a lot of these companies came to the conclusion, like we did, that the amortisation of prior actuarial gains and losses limits a clear picture of your businesses’ underlying operating results,” says John Tus, Vice President & Treasurer of Honeywell International. “Accordingly, we began to recognise the impact of the changes in interest rates and actual returns on plan assets annually.”

The treasurer’s business

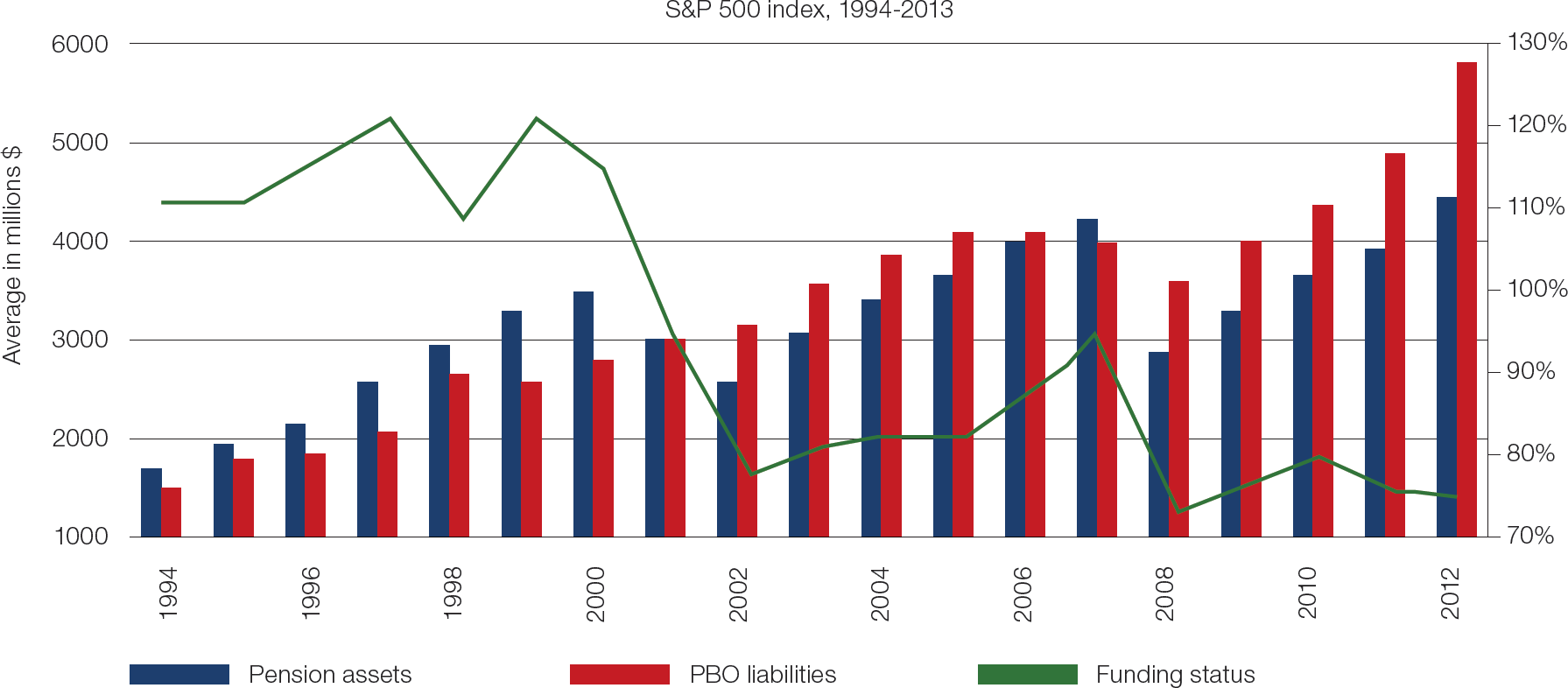

The accounting issue and its impact on profits highlights the implications pension planning can have on overall financial performance, and consequently the work of the corporate treasurer. Historically low bond yields and rising life expectancy in most advanced economies has left global companies burdened with ever larger pension obligations to service. According to recent research by S&P Capital IQ, a vast majority (82%) of global pension plans are now significantly underfunded, while in the US fully-funded plans have all but vanished, with just 38% of the S&P 500 firms able to boast plans funded at 90% or above.

Such deficits are part of the capital structure of the firm and, as such, are taken into consideration by lenders, creditors and investors. To avoid potential conflicts of interest, treasurers do not usually have direct responsibility for pension investments (although some may sit on a pension investment committee). Treasurers do have responsibility, however, for understanding how a pension plan fits strategically and how its management impacts the company. Pensions are very much the treasurer’s business, then, and mounting pension obligations seen post-crisis are proving to be a big headache.

“It can have implications from a credit perspective because, generally, the ratings agencies – with the exception of Fitch – consider underfunded pension obligations as debt,” explains Tus. “And so if a company has a very large, underfunded pension plan that could have implications not only on future cash demands but, secondly, credit capacity. If you have an underfunded obligation, it will limit your credit capacity at your targeted credit rating.”

I think a lot of these companies came to the conclusion, like we did, that the amortisation of prior actuarial gains and losses limits a clear picture of your businesses’ underlying operating results. Accordingly we began to recognise the impact of the changes in interest rates and actual returns on plan assets annually.

John Tus, Vice President & Treasurer, Honeywell International

Because defined benefit pension plans have an economic impact on the company sponsoring them, Tus believes it is critical that each company understand their plan’s design, investment strategy, and the impact that changes in investment returns and interest rates could have on both the funded status of the plan as well as net periodic pension expense. For companies, a weak macroeconomic environment will not only impact the company’s financial performance but also negatively impact the performance of its pension plan.

As well as acting as a check on borrowing capacity, the distortions pension plan performance can have on a company’s reported financial results and how these are perceived by the market may also have a bearing on the pricing of coupons in debt offerings and, of course, the stock price. It is absolutely critical therefore that corporate treasurers, as Tus says, develop an “adequate understanding of the plan’s investment strategy and the potential volatility that could occur as a result of changes in interest rates, and factor in the implications of that with regard to credit metrics and credit capacity”.

Adding value

Other experts in the pensions business agree with Tus on the treasury significance of pension planning. Treasurers, after all, are in the business of managing financial risk – and with many DB schemes having become very significant in terms of size (some, indeed, larger in terms of assets than the companies they are tied to), a spiralling pension obligation is often a risk that the treasurer can ill afford to ignore.

“Defined benefit pensions clearly pose a risk to the business and, quite often, a substantial risk,” says Richard Smith, Consulting Actuary, at Spence & Partners, a company that specialises in advising on and managing DB and final salary pension schemes. “Frequently pension schemes are quite large relative to the business and, given that the treasurer is responsible for managing risks across the company, the treasurer needs visibility of that.”

But short of becoming a trustee and assuming direct responsibility for the plans’ investments, can they do anything meaningful about it? There are numerous other areas connected to pension planning where treasurers might become involved – directly or indirectly – in supporting the company’s schemes. They might, for instance, be required to raise finance from the debt capital markets to cover shortfalls, as Honeywell and indeed a number of international companies did in the wake of the last crisis.

Given the nature of their skillsets, treasurers might also be the ideal people to serve as a form of counsel for the trustees. In the UK, regulatory developments might make this role ever more critical. In its most recent guidance, the Pensions Regulator emphasises the importance of integrated risk management: that is, that trustees should identify and manage the factors that affect the prospects of a plan, especially those factors that affect risks in more than one area. “To me that’s what treasury is all about,” says Smith. “Trustees will have to balance the funding of the scheme with a close eye on the covenant of the employer: how strong the company is and how it would deal with any risks if investments go south. Since treasurers will be familiar with addressing risks in an integrated and a holistic way, they will have the skills that could be utilised effectively in a pension scheme environment.”

Raj Mody, Partner and Head of UK Pensions Consulting at PwC, says that regardless of where it sits in relation to the governance of a scheme, the treasury department has expertise companies ought to utilise one way or another. With the obligations of DB schemes running on over several decades, a means must be found to ensure the asset portfolio continues to meet those long-term cash flow demands. This is something treasurers might be able to help with. “Treasurers should have a good understanding of this challenge, and that is why I am quite excited and energised about the value they can bring,” says Mody. “If you look at the problem properly it is more than just about a deficit calculation at a moment in time, it is about those cash flows. And treasurers can then apply their skills to dealing with that.”

The long view

Although investment horizons of a typical DB pension scheme tend to be much longer than cash managers will be accustomed to, many treasurers may still have some experience in handling longer-term obligations, such as property or equipment leases. It is this sort of expertise that an amenable pension trustee might wish to draw upon as new asset buying and hedging strategies are explored. And should the current low yield environment persist, new investment strategies are likely to be explored by plans on an increasingly frequent basis as those searching for yield may begin to look beyond the purchase of traditional securities to instruments of a somewhat more esoteric nature.

Chart 1: Pension funding

Source: S&P capital IQ compustat pension data

According to global pensions advisory Towers Watson, about $7bn of its clients’ money is now invested in so-called illiquid credit, such as real estate loans, mortgages, infrastructure debt and non-performing loans (NPLs). The money allocated to such assets just five years ago was close to zero. “Clearly the universe is a lot larger now,” he says. At a basic level, funds need assets that can deliver cash flows that meet their liabilities and there is a much wider range of assets today that can help them do that. “Everything from long-term cash flow bond type assets, through to infrastructure to diversified growth funds might be considered,” Mody says. “There is a lot of variety out there.”

More can also be done in terms of risk management, and there are even new derivative products that can be used for hedging non-financial risks to a pension plan, such as longevity. Although still not a commonplace practice, there are easily accessible structures that allow pension schemes to cost effectively transact with reinsurers for the purpose of hedging their exposure to increasing life expectancy. In companies exploring the use of such products, who better to evaluate their efficacy than the corporate specialists in risk management, the treasury? “That is a new development,” Mody says. “There is a structure called Iccaria that effectively allows pension schemes to do that. It was a very complex and opaque process before, but now it can be really transparent.”

A clean slate

All of this demonstrates that while underfunded pension plans are certainly proving to be a big financial headache for many corporate treasurers at the present time, the problem is not an incurable one. On the contrary, there are a whole range of options – some tried and tested and some more novel and experimental – that can be taken to mitigate pension risk.

To begin with, the examples of Honeywell, and more recently Ford, show us that legacy losses need not be a factor weighing on future results; there is a way by which companies who suffered heavily during the post-crisis years can start again with a clean slate. However, the two examples also show us that switching to MTM accounting is not a panacea, rather only a small part of a much broader strategy.

Indeed, prior to switching to MTM accounting both Honeywell and Ford took numerous other steps to address pension funding shortfalls. In the case of the latter, these include the making of close to $11bn worth of contributions since 2012 to help finance its plans, and the paying out lump sums to retirees who give up their pensions that have, to date, totalled $46bn. The measures certainly seem to have done the trick: between 2013 and 2015 Ford’s global pension plans went from being $19bn underfunded to $9.8bn underfunded. Although more recent data is not yet available, given the current trajectory the shortfall may be even smaller now. It was the success of these measures that allowed Ford to press on with the switch to MTM accounting. “Because we’re nearly finished with that strategy…we’re at that point where we can make this change,” Ford CFO Bob Shanks said in a recent interview.

But whether a company ultimately opts to do something similar or take a different approach, treasurers should be involved in the conversation. This is appropriate not only because of the impact pensions evidently have on overall performance, but also because of the role treasurers have in debt issuances needed to plug deficits; the expertise they can bring with respect to risk management; and the counsel some will be able to offer trustees on asset strategies. Pensions are an almost inevitable headache for most corporates and their treasury departments in today’s economic environment, but the expertise and capabilities treasurers can bring to the table may be an important part of the cure.