President Donald Trump’s protectionist leanings led to the US pulling out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, forcing the remaining 11 members of the unfulfilled pact to forge ahead with a new agreement, the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership. With multilateralism under threat globally, many are looking to the newly minted CPTPP to help champion an open, liberal, rules-based trading system.

With Donald Trump as President-Elect having promised to pull the US out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) on taking office, the writing was on the wall for what at the time had the potential to become the biggest regional free trade pact in history, one that would have accounted for nearly 40% of the global economy.

The 12-nation trade deal, the TPP, was the centrepiece of former President Barack Obama’s strategic pivot to Asia policy but Trump, after signing an executive order pulling out of the deal soon after taking office in January 2017, made clear his view that the pact posed a big threat to US jobs: “It’s a great thing for the American worker what we just did.”

And it wasn’t just Trump that had deep misgivings about the TPP – unions in the US as well Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders, the two Democrats who lost to Trump in the race to the White House, were also set against it. Like Trump, they too feared the deal would accelerate US decline in manufacturing, lead to lower wages and increase inequality.

Despite the clear heads-up Trump had given, and equally clear evidence of wider anti-TPP sentiment in the US, the reality of being dumped by the stroke of Trump’s pen was still a massive body blow for the other 11 TPP partners, comprising Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore and Vietnam. Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzō Abe, for instance, had already warned that a TPP without the US – and its market of 250m consumers – would be “meaningless“.

The TPP-11, however, have picked themselves up and dusted themselves down, forging ahead without the US. The US-light bloc, now snappily called the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), officially came into being in December 2018. Soon after, the revised agreement was implemented by six of the TPP-11: Canada, Australia, Mexico, New Zealand, Japan and Singapore. In January, Vietnam also formally implemented the deal.

Also in January, the CPTPP members held their first ministerial-level talks in Tokyo and promptly opened the doors for wider membership: “There is a temptation toward protectionism, but we must not rewind the clock,“Shinzō Abe said. “For all countries that resonate with our philosophy and are ready to accept the TPP-11’s high standards, the door is open. I expect participation from many countries seeking free and fair trade.“Countries and regions ranging from Thailand and Taiwan to Colombia and the Brexit-challenged UK have already expressed interest in joining the CPTPP.

Counting the cost of US blowout

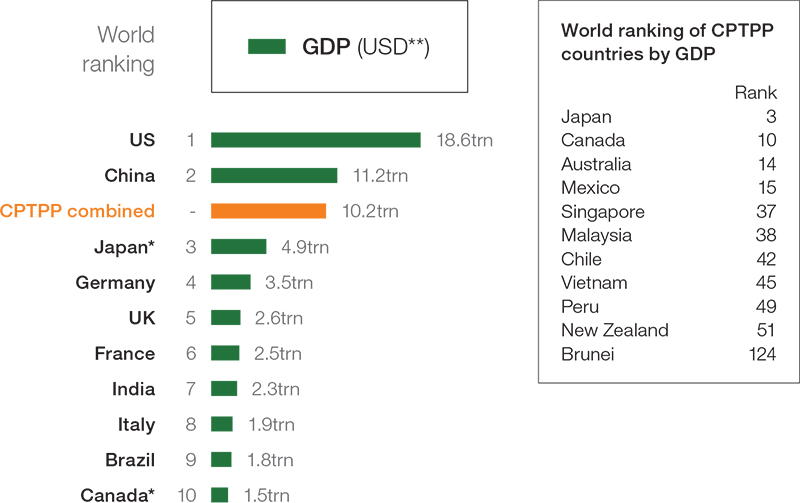

While the CPTPP has some way to go before it can match the potential of the original TPP – it will account for 13.4% or US$10.2trn of the world’s GDP versus the original TPP’s combined 36% or US$29trn – it still amounts to a huge new trading bloc covering 500m people, one that will ultimately see the removal of 95% of the pre-agreement tariffs on trade between participating countries. The first six nations to ratify the agreement alone represent 90% of the group’s total output and 322m people.

The CPTPP agreement itself is largely the same as for the TPP with the exception of some provisions relating to intellectual property and investor-state dispute settlement, which were previously important demands for US participation in the TPP.

One widely cited analysis of CPTPP by the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) indicates that every current member of the CPTPP deal will be a net beneficiary in economic terms. Once fully ratified and implemented, PIIE estimates CPTPP could boost trade for members by around 6%, adding 1% cent to their real incomes by 2030.

At the same time, in terms of trade metrics at least, the US looks to the biggest loser, with PIIE estimating that its real income under the original TPP would have increased by US$131bn annually, or 0.5% of GDP. Furthermore, under the new CPTPP deal, the US not only forgoes these gains but also loses an additional US$2bn in income because US firms will be disadvantaged in the TPP markets.

With the Asia region responsible for the bulk of its profits, HSBC has kept a close eye on TPP and its morphing to CPTPP. Douglas Lippoldt, Chief Trade Economist, HSBC, says CPTPP is “a big deal” even without the US, not only due to its scale but also its open architecture, one designed to accommodate additional members, periodic reviews and updates.

He adds: “The CPTPP’s 30 chapters deliver deep liberalisation in goods, services and trade-related investment. Services are liberalised and investors assured national and most-favoured nation treatment. This leading-edge agreement addresses 21st century challenges in areas such as e-commerce, telecommunication and data issues, including privacy and free flow of data. It also tackles social concerns including the environment, labour, inclusive trade and unfair competition.”

Lippoldt says developing countries such as Vietnam, Peru and Malaysia stand to gain most from the pact in terms of growth, with exports increasing by more than 8.5%, while developed members such as Canada, Australia and New Zealand are likely to see exports rise by between 4% and 5.8%. Developing countries can also look forward to the greatest proportional real-income gains.

He believes the improved competitiveness from increased market openness under the CPTPP framework may also help the members to benefit more fully from engagement in other trade initiatives in the region, such as China’s Belt & Road Initiative or the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership under negotiation between ASEAN and six of its free-trade agreement partners.

Indeed, at the regional level, Asia Pacific seems especially intent on keeping the free trade banner flying high, with several other free trade agreements concluded or under negotiation including the Indonesia-Australia Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement; the Australia-Hong Kong Free Trade Agreement; and the China-Japan-Korea Free Trade Agreement. And earlier this year both Japan and Singapore signed bilateral deals with the European Union, the largest trade bloc in the world. Vietnam, Australia, Indonesia and New Zealand are all also looking to strike a deal with the EU on bilateral basis.

Lippoldt says that, as it stands, it is not only the US that stands to face net losses, albeit modest ones, by not p\articipating in CPTPP. Non-members like China, Korea, Taiwan and Thailand also stand exposed to losses, as some trade is diverted to bloc members. Still, there is the real possibility that at some point in the future some of these countries, including China and Thailand, will reconsider membership. Recently there have even been noises from Washington that President Trump would reconsider joining if there was a better deal to be had.

He says: “In the face of rising protectionist sentiment, CPTPP sends a positive signal in favour of market openness and trade liberalisation. The economic rewards reaped by its members may yet entice other countries in the neighbourhood to join rather than face losses by staying out.”

The world’s top GDPs and the CPTPP

The combined gross domestic product of the 11 Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) members rivals that of China and equates to more than half of the United States’ GDP. Canada, Japan, Australia and Mexico account for nearly 90% of this. The CPTPP will not necessarily change the shape of global trade patterns, but its sheer size makes it a formidable bloc.

*CPTPP countries

**Current USD

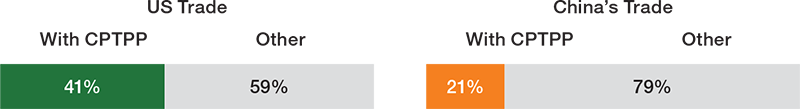

CPTPP trade with United States and China

As major economies, the United States and China will trade heavily with members of the CPTPP. The US already has free trade agreements with five of the 11 CPTPP members and is hoping to forge more deals. Japan and Australia, on the other hand, hope that the United States will return to join the CPTPP.

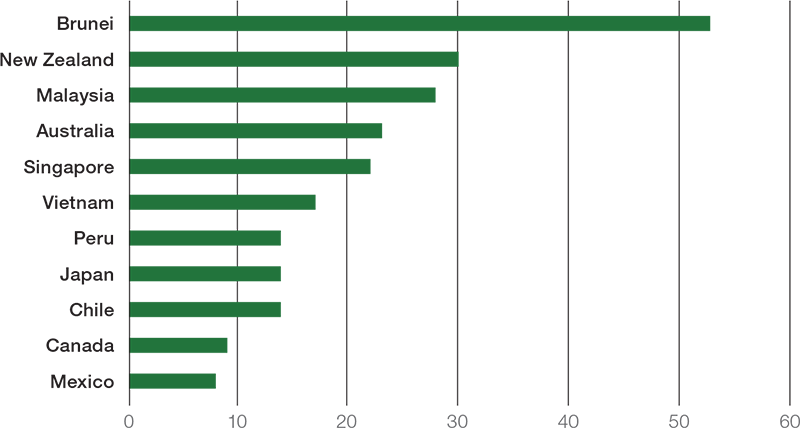

Trade within the CPTPP

The 11 members of the CPTPP hope to increase trade with in the bloc. Among the leading members, this is particularly important for Australia which which thrives on regional trade and hopes to diversify beyond China.

Trade with other CPTPP countries

Percent of country’s world trade

Source: Trade Map, Stratfor 2018

Open for business

Stuart Tait, Regional Head of Commercial Banking, Asia Pacific at HSBC, is also certain about the importance of the deal for global trading and the real-world value of the agreement for firms. While the world awaits the outcome of the trade talks between the US and China, “the CPTPP’s entry into force signals that the desire for an open, liberal and rules-based trading system is very much still alive. Businesses are certain to benefit from greater clarity at a time of trade-policy turbulence – as well as from improved access to 500m consumers,” he says.

Tait says that free trade agreements (FTAs) such as the CPTPP simplify import and export procedures for companies and reduce the cost to trade. For instance, the CPTPP provides for ‘full cumulation’, meaning that businesses in CPTPP markets can use inputs sourced from other CPTPP markets to qualify for preferential treatment within the region.

“With the CPTPP now in effect, there is no better time for businesses to raise their awareness and maximise the benefits that are on offer,” says Tait, pointing to a recent HSBC Navigator survey showing that nearly four in ten (39%) companies in CPTPP member countries believe that the agreement will directly or indirectly help their businesses.

For Lippoldt and his colleague, Shanella Rajanayagam, trade economist at HSBC, a crucial feature of FTAs such as CPTPP is that they help to provide companies with visibility by improving trade policy certainty – a highly attractive feature given ongoing uncertainly and turbulence across the international trading system.

In a co-authored analysis of FTAs – there are 369 in force across the globe – they say that while Brexit, rising protectionist rhetoric and measures by the US, and US-China trade tensions have led to growing uncertainty in the trade outlook, the use of FTAs by firms can help to assure they benefit from preferential or easier access into partner markets, which in turn can help reduce trade costs and boost their business overseas.

And on the face of it, despite the current trade headwinds, businesses globally generally agree with that analysis. A recent HSBC Trade Navigator survey found the vast majority (78%) of businesses across the globe remain positive about the outlook for trade, with over half (51%) of respondents claiming that FTAs will positively impact their business in the coming years. Just over a quarter of respondents do not expect FTAs to impact their business in the medium term, suggesting to Lippoldt and Rajanayagam that there is still significant room for improvement in relaying to firms globally the positive difference FTAs can make to their businesses.

At the regional level, the Navigator survey found that firms in Asia were amongst the most positive about FTAs, although variations exist between countries. Around 60% of ASEAN businesses collectively; 67% of Indian respondents; and 66% of Chinese businesses viewed relevant FTAs as having a positive impact on their business, whilst fewer than 40% of businesses in Japan, Indonesia and Bangladesh considered FTAs helpful to their firms. In Europe, 47% of businesses considered FTAs as beneficial to their business, although UK respondents had a more favourable view (51%), perhaps suggesting some confidence in the UK’s ability to secure trade agreements with non-EU countries post-Brexit.

The voices of the people who did not benefit or who were left out have steered governments across the globe to a ‘go-at-it-alone’ unilateral track.

Jelle Goossens, Regional Treasurer, Barry Callebaut Asia Pacific

More specifically, Lippoldt and Rajanayagam note that while FTAs allow businesses to achieve cost savings from reduced or no tariffs and trade facilitation, many eligible firms fail to make use of tariff relief due to low preference margins, high compliance costs, or lack of awareness. They advise that prior to engaging with an FTA, businesses should determine whether their goods or services are eligible for preferences and how to claim them.

They strongly advise firms to make use of a range of publicly available resources that could help businesses improve FTA usage. Most of these resources are provided by governments or inter-governmental organisations such as the WTO or OECD: “These resources are not only helpful in providing traders with detailed market information or information on customs procedures and how to comply with FTA requirements, but can also be helpful in providing firms with bespoke trade assistance or funding via state-supported trade advisers and trade promotion agencies. In general, most national trade departments provide a good first port of call for any trade-or customs-related enquiries.”

Price to pay

Like Tait and Lippoldt, Jelle Goossens, Regional Treasurer, Barry Callebaut Asia Pacific, hails the CPTPP agreement but is concerned about the absence of the US from the agreement and general global drift away from multilateralism and rise of protectionism.

Goossens says: “While it should still prove a material boost to global trade, and as such a means to improve the livelihood of millions in emerging markets, the fact that we have the CPTPP coming into effect without the United States as a signatory is both a missed opportunity as well as a worrying sign.

“The creation of the world’s third largest free trade area is certainly a feat to be celebrated. Nevertheless, at the start of 2019, it is clear that the overarching theme of the end of multilateralism which we are witnessing on many a front, be it global trade or climate change, is grounds for uneasiness.”

Goossens believes that after little over two decades of globalisation characterised by multilateral platforms, “the voices of the people who did not benefit or who were left out have steered governments across the globe to a ‘go-at-it-alone’ unilateral track”. He says it is inevitable that such an approach is prone to confrontation: it favours the strong, leading to an unbalanced outcome that will always result in one party feeling disenfranchised.

And while such an approach might bring short-term gains for some corporates, Goossens warns it holds dangers for the longer-term and comes at a cost: “Some businesses might capitalise on some opportunities it brings but, overall, the heightened insecurity and increase of friction in trade relationships is a negative and does not add to meaningful economic growth. Even though risk managers, like treasury professionals, might derive recognition for their role in safeguarding the company’s cash flows, it steers them away from the more meaningful added-value tasks they are called upon to fulfil.”