Since it first arrived some 30 years ago, corporates have been able to use the concept of netting to drive efficiencies and make cost savings. Treasury Today goes ‘back to basics’ and looks at the processes involved in netting and what it really means for treasurers.

There are surely few international corporate treasurers, if any, who would not wish to reduce the cost of financial transactions across their organisation. Fewer still would reject greater control and oversight of their cash positions. Whether it is to better understand or mitigate FX, liquidity or interest rate risk, to optimise cash flow and working capital, or simply to reduce the complexity of inter-company payments within a widely distributed group, there is little doubt that implementing a modern netting structure is an answer to many treasurers’ prayers. But if it is so good, why doesn’t everyone do it?

In the early 1980s, netting was a simple but labour-intensive paper-based operation. Today, the many variants can be managed electronically using largely automated in-house or proprietary web-based technologies capable of reaching out to and effectively centralising the cash operations of even the furthest flung subsidiaries.

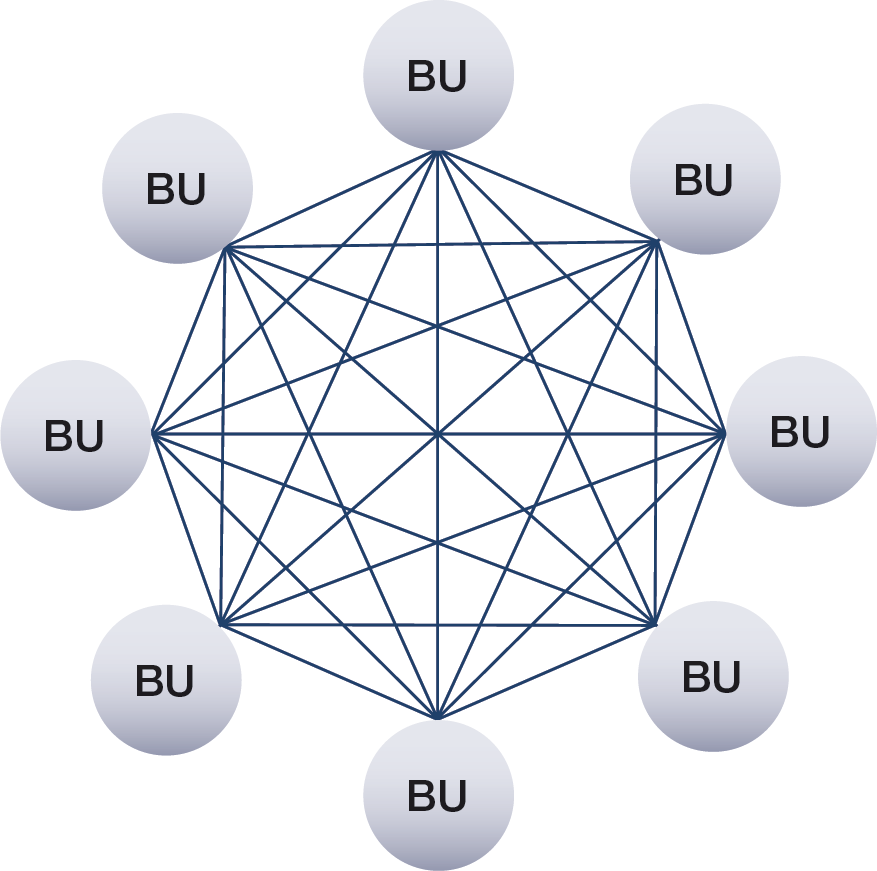

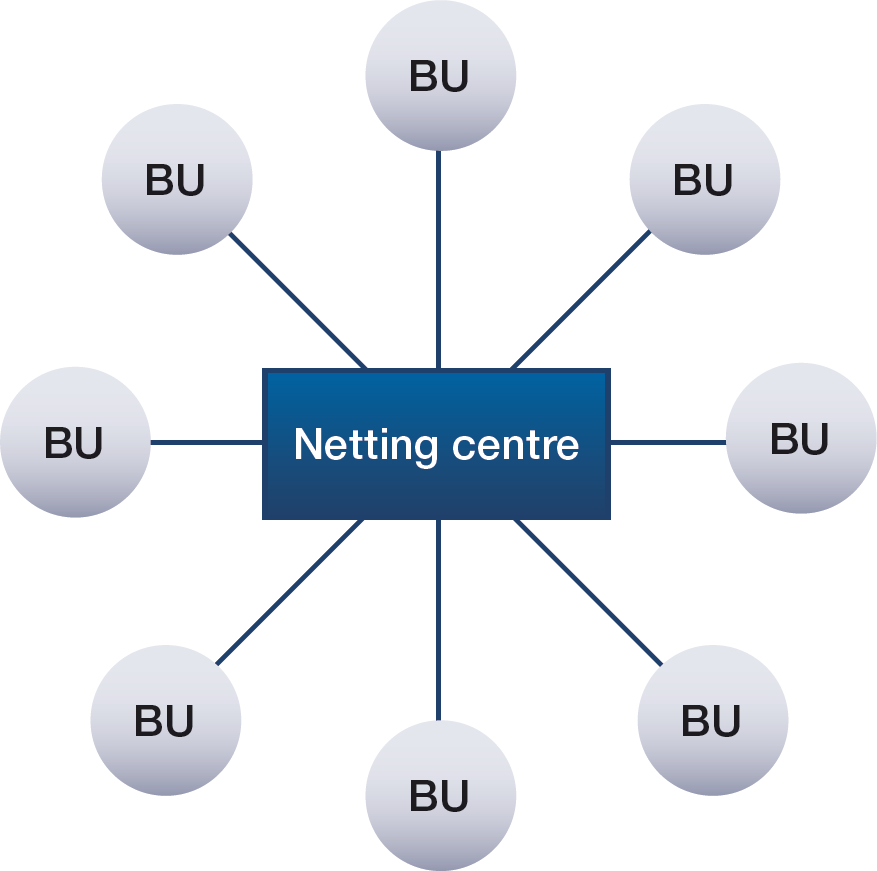

In its simplest form, netting allows an organisation to offset one cash amount against another, reduce the number of payments that need to be made and aggregate the remainder. This may be between two entities within the same group of companies (bilateral netting) or involve many entities (multilateral netting). For multilateral netting, transactions will be executed by a netting centre – a central function established for this purpose – and will take place via the external banking system or internally.

The effectiveness of a netting programme increases the more it is used across a group of companies, however, circumstances may preclude certain entities. In some countries central bank regulation may either restrict the use of netting, impose an onerous reporting regime on all activities or not permit it all. The reach of technology may also self-select those business units able to participate, although access to web-based systems, such as those offered by the tier one banks, will obviously improve access, as will a more standardised internal technology environment.

There are two basic netting options:

Bilateral netting

One entity may agree to net its payments with another group entity for trade over a set cycle (typically monthly). At the end of the period, the entity that on a net level is in deficit makes a single payment to the other party. This reduces the number of payments being made and received between various pairings of entities across the group. No netting centre is involved and payments still need to be made via the external banking system where fess will be charged. For a larger group of companies a more efficient (multilateral) model exists.

Multilateral netting

Multilateral netting, as the name suggests, is a many-to-many scenario where multiple parties may net off their transactions. A single netting centre is required to act as the counterparty to each participating member of the group (usually subsidiaries of the same company but in some cases third-party providers are granted access). Each participant needs to hold an account with the netting centre and payments are only made within the system to or by the netting centre.

What happens during the netting process?

Participants in the netting system must forward copies of all relevant documentation, invoices and payment requests to the netting centre, usually electronically and more often now by direct entry into a netting system. A cut-off date for submissions will be in place for each cycle.

The effectiveness of a netting programme increases the more it is used across a group of companies, however, circumstances may preclude certain entities.

All invoices and payments requests are reconciled and when the netting process is run (normally once a month), unmatched items can be investigated. In some systems, subsidiaries may be able to query data input by other entities within the group to fix the problem without further input from other teams. All matched transactions (credits and debits) will be netted to a single amount for each subsidiary in its chosen operating currency, initiating payments either to its own bank or to the in-house bank, as appropriate. Subsidiaries with negative balances at the netting centre will have to make the payment to the centre. FX rates for all disbursements are typically set by the netting centre (and thus do not include the spreads likely to be included by banks).

Who takes part?

Within a group of companies there will need to be a decision as to which entities can or must participate in the netting centre. Most netting schemes are only open to companies with the same parent. However, in some cases, it may be possible to include non-group (third party) companies where both sales and purchases are made. External participants will need to have sufficient cash flows to be able to benefit group participants but the external entity may be able to net payments to different internal entities within the netting system. Where a third-party supplier receives payments from a number of group entities in multiple countries it may be beneficial to include them, to aggregate payments and reduce the number of cross-border transactions made.

Some commercial sectors have benefitted from the establishment of an industry-wide netting system. Perhaps the most visible is the International Air Transport Association (IATA) Clearing House. It clears and settles accounts payable and receivable (including ticketing and airport fees) for around 500 airlines, airline-associated companies and travel companies across the world.

Most netting schemes are only open to companies with the same parent. However, in some cases, it may be possible to include non-group (third party) companies where both sales and purchases are made.

Single versus multi-currency

For payments, the simplest structural form is a domestic netting system, also sometimes known as single currency netting. This would normally be open to all group entities within a specific country and cover purely domestic currency payments although it could in principle also include euro-denominated participants. Domestic currency netting systems eliminate the need for the different group entities to make numerous intra-group payments, saving on fees.

In multi-currency netting, all the participants in the system are required to send payment instructions and copy invoices, regardless of currency, to the netting centre. The netting centre converts any foreign currency payments into the appropriate netting currency. At the end of the netting cycle, the netting centre makes payments to or receives payments from each participant. These payments will be made through the external banking system and will usually be denominated in the operating currencies of the participants.

As with the domestic currency netting systems, multilateral netting removes the need for multiple intra-group payments. Every netting cycle requires participants to make (or receive) payments only in its operating currency. For entities that had previously made large numbers of foreign currency payments, netting can lead to significant savings in this respect.

The benefits of netting

Where a multilateral netting programme is in place, the benefits are many. These include:

- Reduced payment costs and interest payments. As all external payments are netted, there is only one external payment into or out of each subsidiary, which significantly reduces the total cost of these payments to the group as a whole. Individual business units will not need to operate overdrafts or maintain idle balances to meet their short-term payment requirements. In addition, the total amount of FX purchased and sold will be lower, reducing the amount of FX commission, and a lower number of foreign currency accounts will need to be managed.

- Reduced float. Delays between an initial payment instruction and the receipt of the final payment are reduced. With fewer external foreign exchange deals, cash can be made to work more efficiently during the netting cycle because idle balances and float should only exist at the end of each cycle.

- Known payment date. Each subsidiary in the netting centre knows when it is going to get paid for any inter-company invoices it has issued. Subsidiaries may have to pay their invoices earlier, but they know exactly which day they will receive cash on the invoices that they are expecting. This brings stability to the timing of cash flows – and improved forecasting – within the organisation.

- Banking consolidation. The concentration of payments and receipts means treasury can choose to have one bank or at least consolidate the number of banking partners its does its FX with. Treasurers thus can reduce the number of banks that they are exposed to from a settlement perspective. Savings are also available on the FX spread because the greater the size of transactions made, the greater the potential for cost savings.

- Simplification for subsidiaries. They no longer have to decide which currencies they need to buy, instead paying and receiving in a single currency. This means local treasury functions can focus on adding value elsewhere.

- Reduced operational risk. This comes as a benefit of no longer relying on manual and de-centralised payment and settlement processes.

- Hedging efficiencies. A netting cycle mean treasurers know the specific date that they are exposed to FX risk, allowing them to hedge efficiently and effectively as it reduces timing gaps in their hedging programme.

- Payment discipline is improved. Trade terms can be shortened between partners if cash flows are predictable.

- Arbitration service. The netting centre effectively takes on the role of neutral dispute manager.

- Early warning of exceptions. Payment matching will be automated as invoices are sent to the netting centre. If an invoice is not matched, advance notice of a potential problem can be issued and the problem rectified before too much time is wasted identifying the source of error.

- Cash management information is improved. Because intra-group payments are recorded at the netting centre the information can be used to generate various reports including, for example, management information looking at the fees and spread savings achieved, and regulatory information required by certain jurisdictions.

The cost of netting: technology and models

The costs of a netting structure will vary according to what is required but in the first instance there will be a need to persuade all entities to get on board with the programme and any resistance to change must be managed sensitively to encourage rather than demand buy-in. Almost certainly training resources will be required to ensure that all relevant subsidiaries are up to speed with the processes that underpin the netting system once it is in operation.

There will be an implementation cost to consider. Existing technologies and processes across the group will need to be standardised as far as possible. This may not be easy in difficult geographies where communications are less reliable, in which case other means of data transfer may need to be found (even if it means email). Initial software purchase or an upgrade or extension of an existing system (such as a TMS, ERP or dedicated third-party netting software) must be factored in as must ongoing licensing and maintenance costs. Consideration must be given in each case to the ease of implementation and roll-out of the solution, including the ease with which the solution integrates with existing technologies. The functionality and scalability of the system and any likely costs in configuring it to fit the company’s own needs should also be taken into account. It may be necessary to adopt a phased, rather than big bang-style roll-out to make the project more manageable.

There will be a cost associated with running a netting centre although some of the administrative work previously performed by group entities will be diverted here, with subsidiary staff preferably diverted to other added-value work.

The cost of any additional accounting and legal matters related to the netting centre will have to be taken into consideration. Complexity and cost will depend on location but taxation on inter-company payments and, for cross-border netting, any central bank requirements, must be met head-on. There will also be a requirement for the accounting functions of participating entities to work out how to treat the various transactions. Within the cash receipts and accounts payable books it may, for instance, be necessary to divide netted transactions into respective individual payments and receipts.

Outsourcing of a netting operation is an option offered by some banks and treasury service providers. There will be costs associated with establishing and running of a netting service and it may be more provident to outsource the running of the netting system. A cross-over of duties may be possible, where a corporate is able to take on the netting task but is comfortable handing over FX settlement, for example, to its banking partner. However, the nature of netting means full outsourcing is not possible: around 20% of the workload inevitably stays in-house in the form of confirming and sending payment requests plus of course the aforementioned essential accounting and tax treatments and documentation of flows for audit purposes.

Moving ahead

Adoption of netting amongst the corporate community is far from across the board. This may be because there are a number of variables that need to be tackled, not least being the regulatory hurdle in some jurisdictions and, closer to home, the lack of standardisation of technology internally. These issues are not insurmountable. For a process that has been developing slowly over the past 30 years or so, netting remains a simple yet effective proposition where the benefits are clear, particularly for MNCs that have a high volume of inter-company invoicing and cross-border, cross-currency transactions.

More detailed information on netting and other cash management processes can be found in the Treasury Today Best Practice Handbook on

European Cash Management 2014.