In this series Treasury Today has shone a light on some of the greatest financers of our time and also highlighted the crimes and cult of personality that surrounds some of the world’s most notorious white-collar criminals. In this profile we take a look at Japanese trader Yasuo Hamanaka and his $2.6bn manipulation of the copper market.

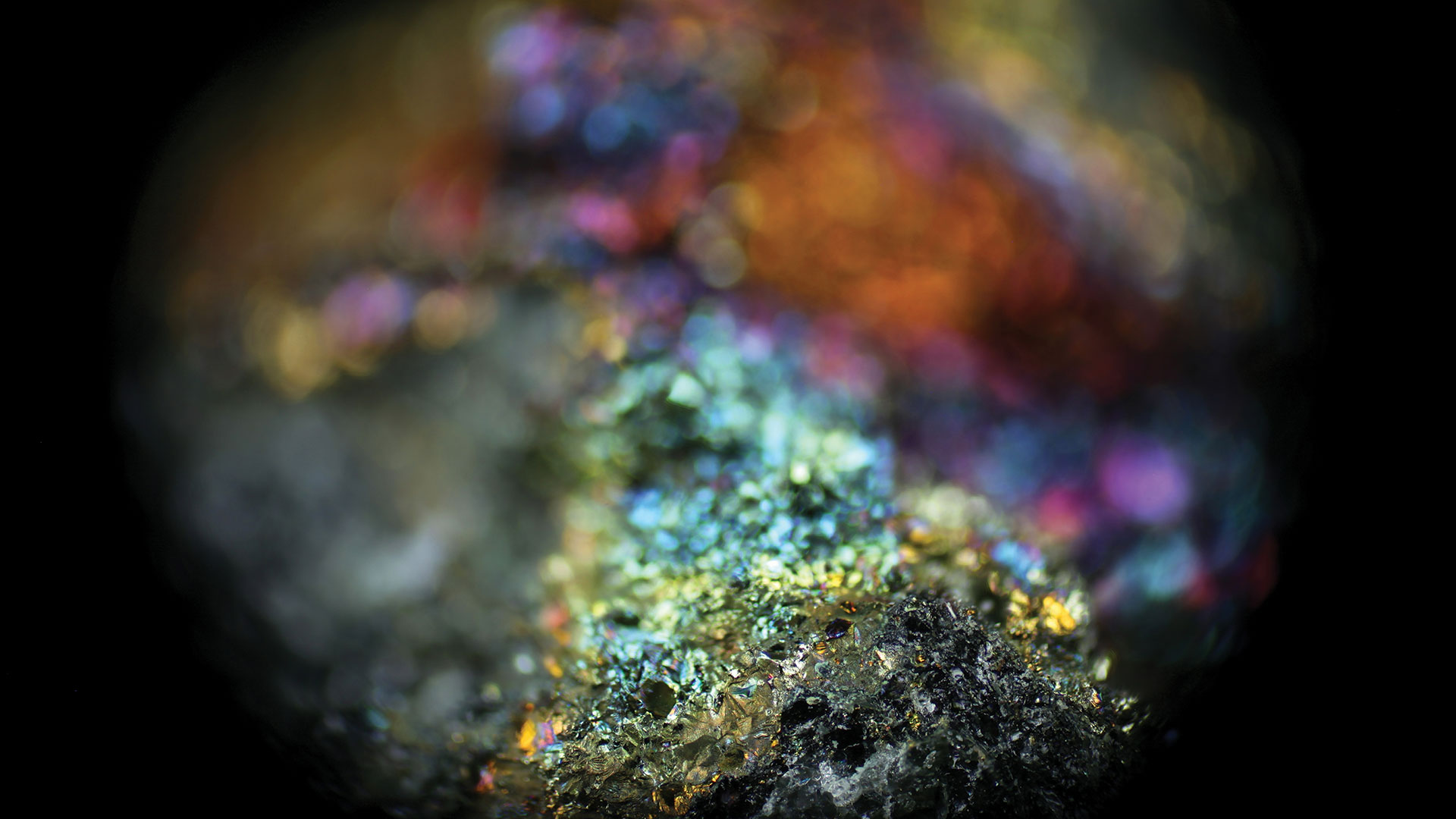

When compared to other metals, copper with its reddish brown colouring is not the most glamourous. Yet it has an illustrious history, being one of the first metals to ever be extracted and used by humans, making a vital contribution to sustaining and improving society. Today its usage is abundant – although often hidden – being a key component in construction, power generation and transmission, electronic product manufacturing, and the production of industrial machinery and transportation vehicles.

Given how crucial copper is to modern day society, the metal is a heavily traded commodity with billions of dollars’ worth being exchanged each year – primarily in London, New York and Shanghai. In fact, copper is sometimes referred to by analysts as ‘Dr Copper’ as it can be used as an indicator of the health of the global economy due to its widespread usage. It begs the question, therefore, how a single ‘rouge trader’ named Yasuo Hamanaka was able to manipulate the market over a decade to the tune of $2.6bn.

Despite the magnitude of his crimes, very little is known about this Japanese trader. Unlike Nick Leeson, Bernie Madoff and the other white-collar criminals profiled in this series Hamanaka hasn’t had newspapers scour through his past. Nevertheless, the accounts that do exist paint the picture of a relatively unspectacular Japanese salary man known for grey suits and steel-rimmed glasses.

Within the relatively niche world of copper trading, however, Hamanaka was a legend, gaining the nicknames Mr Copper and Mr Five Percent on account of controlling 5% of the global copper market.

Within the relatively niche world of copper trading, however, Hamanaka was a legend, gaining the nicknames Mr Copper and Mr Five Percent on account of controlling 5% of the global copper market – the latter nickname was previously given to Armenian oil magnate Calouste Gulbenkian. Hamanaka was known to be ruthless with a strong self-belief and confidence and it was these attributes that played a big role in his crimes.

A losing start

Hamanaka’s story begins in 1986 when he was selected to lead a team of copper futures traders at Sumitomo – a company where he spent his entire professional life, having previously bought and sold physical copper as a trader for the non-ferrous metals department. Although the reasons for Hamanaka’s actions are not entirely clear, it is widely accepted that he began manipulating the market following a disastrous first few years in his new role. During a period spanning from 1986 to 1989 the Sumitomo copper team suffered big losses, largely as a result of the purchases and sales of physical copper and the speculative futures dealing that Hamanaka engaged in to recoup these.

During this period, it is reported that Hamanaka lied to his superiors, destroyed documents, falsified trading data and forged signatures to cover his losses which he kept in an unauthorised trading book. It was after this unsuccessful attempt to recover his losses that Hamanaka devised a long-term strategy to squeeze the market to put Sumitomo, and himself, at the heart of copper flows.

Squeezing the market

It is reported that Hamanaka began executing his complex plan in 1989 after connecting with David Campbell, the president of metal trading firm RST Resources. Allegedly, it was during this initial meeting that Hamanaka expressed his desire to squeeze the world copper market and thus drive up the price. To do this, Hamanaka would utilise the full arsenal at his disposal in the form of Sumitomo’s large copper supplies and the company’s capital. After the meeting Sumitomo quickly became RST’s biggest client, until Campbell left the company and founded Global Minerals & Metals Corp (Global) – unsurprisingly Hamanaka and Sumitomo followed.

It was at this stage that Hamanaka began to implement the next phase of his strategy and create the appearance of a legitimate commercial need to purchase large quantities of physical copper. Working with Global, Sumitomo entered into a number of contracts by which it would purchase copper on a monthly basis between 1994 and 1997 – contracts which contained odd participation and price provisions. These provisions meant that the merchant firm was required to pay Sumitomo 30% of the difference between the market price at the time of shipment and the minimum price on futures contracts purchased to hedge the supply contracts. Whenever copper prices rose above the pre-established minimum price, the merchant firm and Sumitomo would share in the price appreciation. The flow of the deals saw Global purchase copper warrants from producers, who in turn would sell the physical copper to Sumitomo, who would then sell the majority of this back to the producer. The rest would be warehoused.

With this seemingly legitimate flow of copper running through Sumitomo, Hamanaka was able to begin hedging, purchasing as many future contracts as he could on the London Metal Exchange (LME) – the world’s largest exchange at the time which essentially dictated the price of copper. To do this Hamanaka – supposedly without the knowledge of his superiors – opened up an account with Merrill Lynch and gave permission for Global to utilise this and begin trading on behalf of Sumitomo.

In the closed circle of copper trading it was well known what Hamanaka was doing.

It didn’t take long for Global to establish a hefty long position in copper futures – owning positions on 780,000 metric tons by September 1995. In a short space of time, Sumitomo, working with a handful of other metal brokers, owned around two million tons of copper futures. It was here that the fruits of Hamanaka’s plan came to bear as he unwound the futures positions allowing him to begin generating significant profits and control the copper cash supply. This position and the structure of the deal gave Hamanaka the power and ability to manipulate the market and drive up the price of copper to artificial highs.

In doing so, not only was Hamanaka and Sumitomo able to profit from this directly by selling their assets, they were also able to leverage other revenue streams. For instance, as one of the world’s foremost copper dealers, Sumitomo handled a large number of other copper transactions – aside from their own. It therefore earned commission on these transactions and the higher prices meant Hamanaka was able to help Sumitomo earn impressive profits and be regarded as the saviour of the company’s copper business.

A badly kept secret

In the closed circle of copper trading it was well known what Hamanaka was doing. But his strategy was protected because of the regulatory shortcomings of the LME which required no mandatory position reporting, unlike in the US for example, where this was commonplace. As a result, nobody except for Hamanaka and his inner circle knew how much of the market he controlled and also the levels of cash he held in reserve. Some brave traders tried to short-sell, but this proved futile as the sheer volumes of capital that he had at his disposal meant that he could inject cash into his position and simply out-last the short-sellers. With no hard evidence for the regulators, most in the market eventually just gave up and let him do as he pleased.

There were however those who had some evidence of wrongdoing, yet even this wasn’t enough to bring down Mr Copper. A Business Week article alleged that in 1991 a copper broker called David Threlkeld was asked by Hamanaka to backdate a fake copper trade worth $425m. Threlkeld refused and subsequently handed over the letter to the then LME Chief Executive David King – something it supposedly investigated before concluding that the matter was outside of its scope. Threlkeld also reported another deal, this time with the Securities and Futures Authority (SFA); however, the claim again failed to see Hamanaka investigated. Yet, there was clearly some suspicion about Hamanaka and his activities. As a Business Week report claims, between 1992 and 1995, regulators and officials from the LME quizzed firms trading on behalf of Hamanaka on his activities.

Downfall

Of course, all good things must come to an end and for Hamanaka his scheme began to unravel in 1994 following the opening of an LME warehouse in California, which meant that Hamanaka’s actions began to directly impact the US markets. The downfall took just under a year to manifest and in Q4 1995 the price of copper soared and cash in the market dried up as a result of copper entering the California warehouse and never leaving. The result was ‘backwardation’ a market phenomenon where the spot or cash price of a commodity is higher than the forward price – something that often signals somebody is trying to control the market.

Interestingly, in many respects it was Hanamaka and his own hubris which caused his downfall, rather than a flaw in his strategy.

As we have seen, this didn’t give other parties the ammunition necessary to investigate Hamanaka given the rules of the LME. But, what did happen was that prices on the American exchange were impacted. LME copper futures began trading much higher than those on the US Commodity Exchange, leading physical copper to move to the LME. As a result the US Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), less restricted than the UK regulators, began to investigate in 1995.

From this point on the scandal began to unravel at pace. The initial investigation uncovered the unauthorised accounts with Merrill Lynch, which Hamanaka had established and were reported to Sumitomo’s senior management. It also apparently received a notice of $200,000 bank credit associated with its copper trading activities that could not be reconciled. According to some reports Sumitomo relieved Hamanaka of his duties around this time, however the official line from the company was that he had been transferred away from trading to a more general role. Either way, the game was up and he confessed to conducting a number of unauthorised transactions which incurred serious losses which he tried to cover by cooking the books, on 5th June 1996.

Ironically, on his release from jail in 2005 Hamanaka expressed his amazement at the record prices of metals.

Interestingly, in many respects it was Hanamaka and his own hubris which caused his downfall, rather than a flaw in his strategy. As a Business Week article from around the time highlights if he had simply sold some of his copper at a loss rather than try to drive prices even higher he may have avoided the CFTC investigation and Sumitomo would still have had huge profits rather than losses.

As is often the case with such scenarios, questions have been asked regarding how much Sumitomo knew about Hanamaka’s activities and whether they just turned a blind eye while he was bringing in substantial profits. Analysts have certainly expressed their doubts that he could pull off a scheme of this scale without help. Yet, the company remained firm in their defence, claiming that Hamanaka acted alone.

Counting the cost

The financial damage of Hamanaka’s actions to Sumitomo was substantial. The company initially announced that Hamanaka lost as much as $1.8bn – the largest loss by a single rogue trader. This number was adjusted to $2.6bn – 14 times the amount the company earned in 1996 and 40% of its net worth – in September 1997 because the company had to close out the complex trading positions established by Hanamaka in a market where the price had plunged. Despite the gargantuan number – higher than the losses incurred by Nick Leeson at Barings Bank – Sumitomo was able to swallow the losses and continue trading.

What’s more, losses were also incurred through fines totalling over $150m and the former directors of Sumitomo agreed to pay $3.55m – half of their retirement benefits – to settle the shareholder lawsuit filed against the company.

Away from Sumitomo, other banks involved in the scandal also felt the pinch as fines rained down on them for (unknowingly) assisting Hamanaka. Merrill Lynch was fined a total of $25m from both the LME and the US CFTC. Sumitomo themselves also filed a suit against Chase Manhattan, UBS and Credit Lyonnais for their alleged roles in helping fund Hamanaka.

Hamanaka himself paid a significant price for his actions. In 1997 he pleaded guilty in a Japanese court to his illegal trading and was sentenced to eight years in jail. Having since been released Mr Copper has reportedly began trading again. Ironically, on his release from jail in 2005 Hamanaka expressed his amazement at the record prices of metals.