For many years, the West has been trying to compensate for the decline in its competitiveness by pursuing ever more macroeconomic stimulus. In the US, Trump is trying to encourage the Fed to lower interest rates considerably faster (partly to absorb the impact of the trade war), while Boris Johnson plans to implement robust fiscal stimulus in the UK, in order to absorb the impact of Brexit. This is why it is currently crucial to assess whether even more stimulus will indeed provide the required compensation. There are a number of reasons to be sceptical.

First, more and more economists are concluding that further stimulus leads to less and less additional economic growth. They point out, for example, that the tax cuts implemented in the US at the end of 2017 have boosted profits and share buybacks considerably but this has not led to far higher wage increases or higher economic growth. In 2018, growth was around 3%, but it has since fallen back to approximately 2%.

Second, EMU interest rates have been reduced to -0.4%, and a growing number of bonds are yielding negative interest rates. In spite of this very loose monetary policy, Europe has closely approached a recession and deflation.

Third, debt/GDP ratios have almost reached record levels virtually everywhere in the world. It is essential that asset prices stay high if stimulus is to boost the economy. (This concerns prices of shares, bonds, and property, et cetera.) Failing this, the value of assets will be too low in relation to the debts, as a result of which the debt mountain will collapse.

It is generally believed that the central banks are able to control this via monetary policy. If asset prices threaten to decline too much, the central bank will be able to turn on the money tap and boost asset prices. However, share prices in Europe and Japan have failed to reach former highs for a long period of time, despite the fact that an ultra-loose monetary policy has been pursued in these territories. It therefore appears that a very loose monetary policy can be overshadowed by poor underlying fundamentals. The question is whether this will happen now as a result of the trade war.

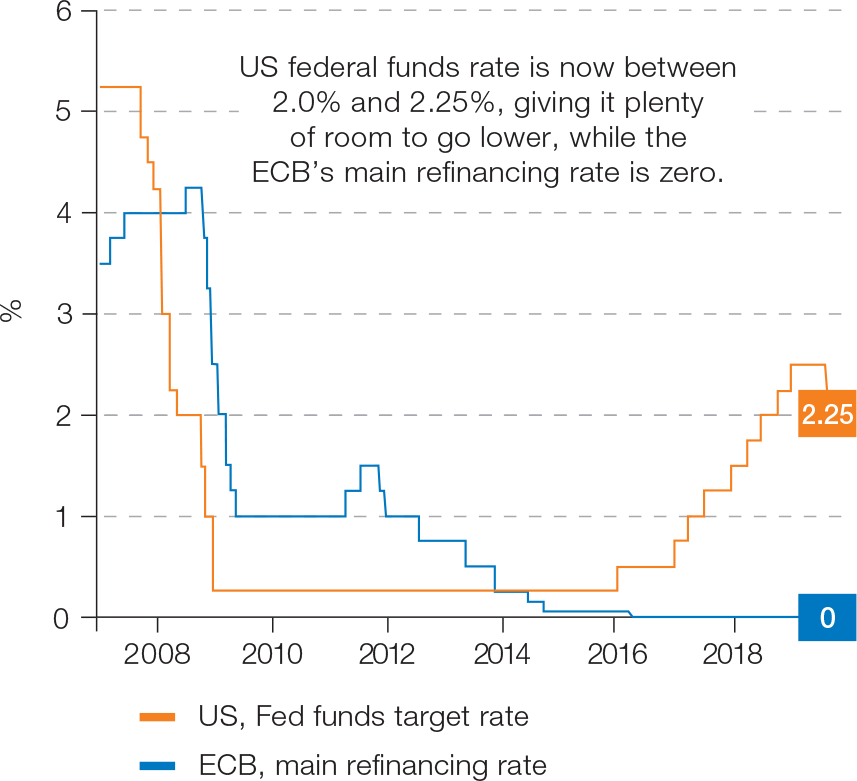

Furthermore, there are many doubts about the potential of further monetary easing, as outside the US and China, the scope for further monetary stimulus is very limited. This makes the situation very risky for investors, as it will be much harder for central banks to absorb the impact of any negative shocks; if one or more shocks lead to a rapid increase in credit spreads and leveraged companies experience difficulties to refinance, default rates will go up as a result. A loose monetary policy will barely have any impact here.

The Fed has much more room to manoeuvre than the ECB

Source: Refinitiv Datastream/ECR Research

The dollar squeeze

In addition to the previous points that cast doubt as to whether a looser monetary policy will boost asset prices to far higher levels, there is a risk of a dollar squeeze. The dollar is subject to a number of downward forces.

- It is generally argued that the dollar will weaken once the Fed lowers its rates. Interest rates either cannot or have barely any room to decline further in many other countries, as a result of which the interest rate differential shrinks, which is negative for the dollar exchange rate.

- More and more countries mistrust Washington, in the sense that they are concerned that the US will block their dollar assets if they do something that displeases the US. This is why they reduce their dollar reserves. This, in turn, increases the supply of dollars on the foreign exchange market.

- The US could intervene in the foreign exchange market to push down the dollar. Concerns about this alone limit the demand for dollars somewhat. However, we do not want to attach too much weight to this argument, as the government can only sell dollars to a limited extent. The Fed is able to sell far more dollars, but is unlikely to decide to sell dollars any time soon because history shows that interventions will only work if the fundamentals change in tandem and other central banks intervene as well. Both factors are not at issue (at this point).

Upward forces

We believe that these downward forces are eclipsed by upward forces.

- It is not the case that other countries do not effect rate cuts or only effect limited rate cuts because their economies are doing well. Their economies generally perform considerably worse than the US economy. However, these countries can no longer counter this effectively because interest rates cannot be reduced any further in practical terms. In a scenario where the US has this scope, the US economy will perform increasingly better than the rest. This means that the highest returns can be achieved in the US. This largely compensates for a shrinking interest rate differential.

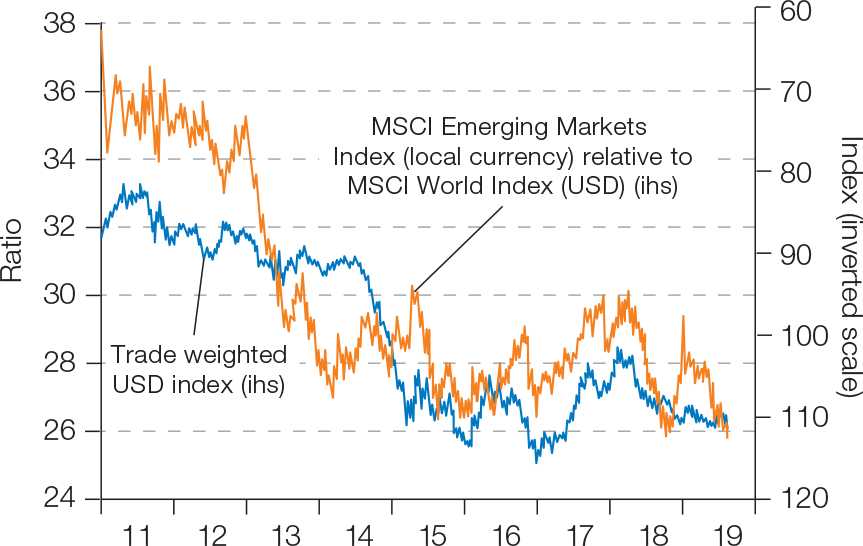

- China has lowered the yuan as a result of the import tariffs. In addition, production chains are at risk. For many emerging markets, this comes down to a deterioration of their competitive position and therefore downward pressure on their currencies. However, said markets cannot allow their currencies to decline extensively because they generally have massive dollar debts. The more their currencies decline against the dollar, the more the dollar debts will bear down on their economies. This is why they generally have no option but to keep their interest rates relatively high. It also means that they can barely compensate for the negative impact of the trade war on their economies. This is currently clearly reflected in stagnating global trade. The emerging markets and Europe rely more on this than the US. This makes it even more appealing to hold dollars, and so on. Once this becomes evident and the dollar exchange rate goes up rather than down, more and more parties outside the US with dollar loans will be inclined to repay their loans ahead of schedule. This, in turn, creates even more demand for dollars.

- This brings us to what is perhaps the most important issue: where should investors with a great deal of money consider putting their funds at present? Ultra-low interest rates have made bonds unappealing in many countries, whilst the trade war makes it riskier to invest in shares. The US is the only place where a considerable return can still be achieved. If the dollar also has a good chance of rising, then this is the safest investment at present.

A stronger US dollar often means trouble for emerging markets

Source: Refinitiv Datastream/ECR Research

In conclusion, we foresee financial market volatility continuing in the stock and bond markets, with rising credit spreads as one of the likely outcomes. Additionally, we believe that the dollar will stay a strong currency for the time being and that it will rise against many currencies, possibly resulting in a dollar squeeze. This is unlikely to be changed significantly by a looser monetary policy inside and outside the US.