After a very strong increase in 2022, inflation is finally under downward pressure. In the summer and autumn of last year, prices of energy and food declined considerably as a result of a milder winter in the west, better export opportunities to transport food from the Ukraine and Russia, and the decline in global economic growth. With regard to the latter, however, there are glimmers of hope if lockdowns in China end and Beijing is willing to stimulate the economy a little more.

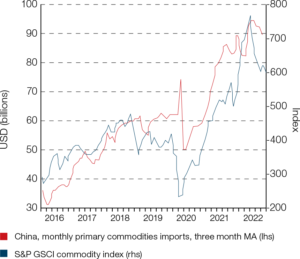

Stronger Chinese economic growth could soon result in more demand for commodities. This, in turn, could lead to an end to the price declines of many commodities or even new price increases. This would exert upward pressure on inflation in the West. On the other hand, without lockdowns, many supply routes could recover, which would actually depress inflation in the West.

However, we are quite sceptical as to whether events will pan out like this. The coronavirus could spread very rapidly in China with the lifting of most lockdowns. Since most Chinese have not been vaccinated or have been vaccinated with a poorly effective vaccine, they have little resistance, not even against the Omicron variant. Omicron generally caused only mild symptoms in the West, but this was primarily because resistance rates were far higher here, either because of good vaccines or due to previous contraction of the coronavirus. Because of all the lockdowns, this does not apply to most Chinese however.

In short, it is favourable for the Chinese and global economy that lockdowns will be largely lifted, but we fear this could result in very high sickness rates, to the extent where the Chinese economy will barely improve, on balance.

We are also less optimistic for the longer-term, both in terms of Chinese economic growth and the commodity demand from this country. This has to do with the changed world following the outbreak of the Ukraine war. Indeed, the West has developed a very different view of the rest of the world due to Russia’s behaviour. The reasoning used to be that if Russia became increasingly integrated into the Western world through the supply of a wide range of commodities to the West, it would also adopt an increasingly less hostile stance towards the West. Based on this view, there was nothing against Western companies increasingly stepping up investment in Russia. The situation with regard to China was slightly different. The West assumed that the more capitalist and richer China became, the more democratic it would become.

In both cases, however, disappointment has ensued. In turn, the above means that more and more Western companies that have invested in Russia and China or have started producing there, have started to wonder whether this is still safe. We increasingly see a Western, a Russian and Chinese bloc emerging, making it increasingly difficult for the West to continue to trade as before. Western companies in Russia and China could suddenly face major restrictions or even be shut down. At the same time, the West will increasingly restrict exports of technologically advanced products to Russia and China. In short, restrictions on global trade will harm the Russian and Chinese economies for the time being.

However, the increasing reluctance among Western companies to do business in China and Russia extends beyond these two countries too Indeed, it also applies to other countries with a dictatorial regime. This means that Western companies will ultimately increasingly try to produce domestically or at least close to home. However, they started producing overseas for a good reason. This happened because almost everything was cheaper there, so the repatriation of production will generally increase costs. Furthermore, it will have important consequences for the Western labour market:

- The workforce in the West will shrink for demographic reasons. The repatriation of production will tighten the Western labour market even more. This will therefore also result in additional wage increases, especially as support for more immigration (which could make the labour market less tight) is lacking.

- Globalisation has equated to a global surplus of labour. When high wage demands have been made in the West, companies have been able to relocate to emerging markets if wages rose considerably. This is how globalisation depressed wage increases in the West.

Chart 1: Slowing Chinese demand has contributed to downward pressure on commodity prices

Source: Refinitiv Datastream/ECR Research

Stagflation

The above will result in the following picture, among other consequences:

- Both the US and European economies will increasingly move towards a recession and this will put downward pressure on inflation.

- China’s intention of lifting of the lockdowns has fuelled hopes that economic growth in the country will soon pick up. However, we doubt this because it will be replaced with high sickness rates.

- In the longer-term, the gradual end to globalisation will be accompanied by upward pressure on wages and prices.

It is important to realise that tight labour markets will result in more upward pressure on wages and inflation compared to recent decades. This is also the reason why Western central banks have no intention of responding immediately with rate cuts once the economy and inflation decline sharply. They are afraid that inflation will rapidly rise again via additional wage increases if they hit the gas too quickly.

High debt levels will complicate the picture if the recession becomes deep (total debt/GDP ratios are at or near record highs almost everywhere). The markets are therefore increasingly assuming that central banks will pursue a kind of middle-of-the-road policy by depressing growth below potential – around 1.75% in the US and around 1% in Europe – while keeping it above 0%. Unemployment will rise when growth is below potential. This, in turn, will exert downward pressure on wage increases. Unfortunately, this process is very slow. If growth just exceeds 0% for a long period of time, it will have two major drawbacks:

- If inflation declines slowly in this scenario, interest rates will remain high for the time being. This combination of low growth and fairly high interest rates could easily trigger another credit crunch.

- The slightest internal or external shock will be enough for the economy to lapse into a deep recession.

Economies can withstand this risk, but only for a short period of time. However, as mentioned before, wage increases and inflation will only decline gradually with a growth rate of between 0% and potential growth. Low growth will therefore have to be maintained for a long time.

Our conclusion is that a growth rate between 0% and potential growth could briefly be a target, but it cannot be sustained for long. In this case, there is only one option left. This is an option that was almost always resorted to in the past, where the economy is stimulated to the point where inflation rises. In other words, the current target of 2% inflation is abandoned, and inflation is kept above this level. The major advantage of this policy is that higher inflation will alleviate the debt burden. The excuse for such a policy may well be that all manner of studies show that inflation will only have a really negative impact on economic growth if it exceeds 5%.

The result will be stagflation, which will have profound implications for corporate strategies as well as the availability of and price of credit.