A lot is written on the coronavirus, the effects of the lockdowns on economic activity and the appropriate measure to stem the economic fallout. However, this crisis will also have important long-term consequences. One of them is a likely change from deflationary pressures to higher inflation.

At first sight, a collapse in demand due to the corona-crisis is deflationary. However, supply is constrained at the same time. It’s therefore difficult to tell whether the lockdowns are conducive to deflation or to inflation. Most importantly, however, the economy is contracting sharply while debt is rising fast. As a result, total debt/GDP ratios will rise to even higher levels. This entails the risk that the financially weakest companies and countries will be unable to honour their debt obligations in full, leading to losses and financial problems elsewhere. In other words, the risk of a domino effect on bankruptcy figures is increasing. In this case, a negative deflationary spiral will threaten, as was often the case in previous crises, for example in the 1930s. During this crisis, deflation coincided with a massive economic decline, very high unemployment, a collapse in share prices and ultimately very dire social consequences.

Paid for and free lunches

However, there are two major differences between then and now:

- Keynes’s theories only became commonplace well into the 1930s. He suggested that the government could absorb a large part of the impact by raising its deficits to a considerable extent.

- The Gold Standard applied at the beginning of the Great Depression, which made it very difficult for central banks to intervene on a large scale.

This is different in the current situation. Governments know that they have to significantly raise their deficits in a crisis, while central banks can create money at will and can cut their rates as they please. However, Milton Friedman has shown that there is no such thing as a free lunch. If the above is done to excess, inflation will ensue and entirely different problems will arise. This is particularly the case if the central bank funds soaring public deficits by creating far more money.

However, there is no direct relationship between money creation and inflation: a great deal of money can be created without rising inflation – or it could be that inflation rises at a far later stage. This is because inflation is not only influenced by the amount of surplus money, but also by the velocity of money. If company A borrows money from the bank, it uses it for a purpose. It could build a new factory, for example. Companies and people who do the construction work are paid for this by company A. Most of this money ends up in the banking system, so that a loan can be issued with the same money, and so on. The speed at which this happens is called the turnover rate – or velocity – of money.

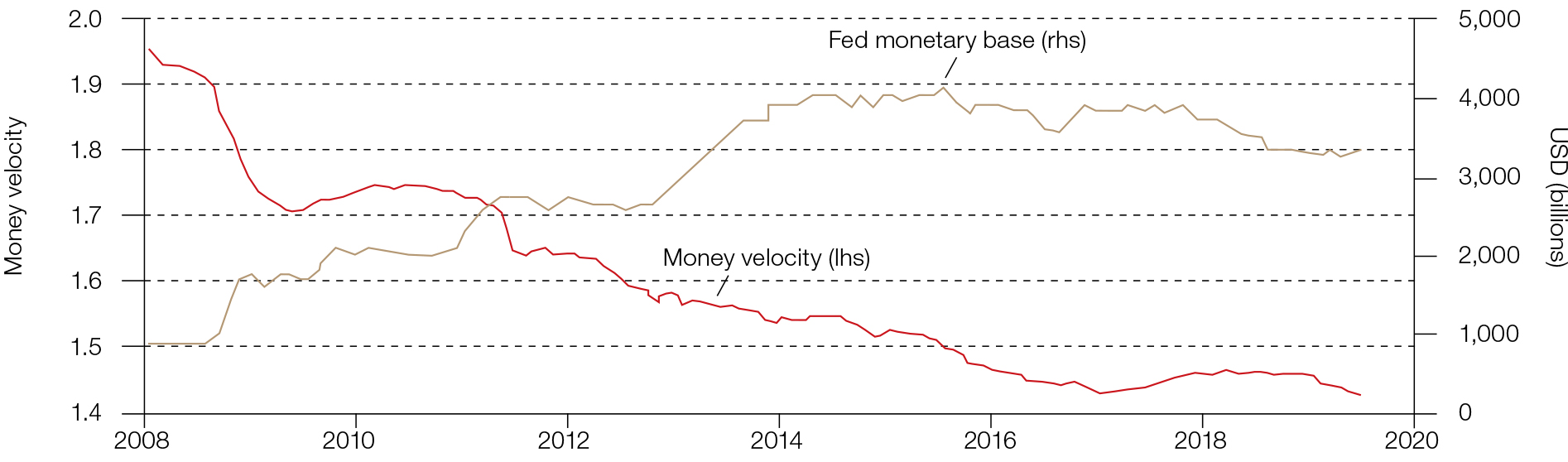

Friedman assumed that the turnover rate of money would remain fairly constant over time. In this scenario, there is indeed a fairly close relationship between the amount of money that has been created and inflation. However, this was not the case following the credit crisis in 2008 – because the credit crisis made lending more difficult, which caused the turnover rate to decline considerably and kept a lid on inflation.

This does not mean that Friedman’s theory is completely off the mark. The combination of considerable money creation and a decline in the turnover rate guarantees that interest rates decline considerably and that far more money is created than the real economy is able to absorb. This ensures that the additional money largely flows to the asset markets (bonds, shares, property, etc). This is why asset prices are pushed up to ever higher levels. Ultimately, asset inflation will arise rather than consumer price inflation. It will not stop here: higher asset prices improve the balance sheets of companies and households, which will lead to an increase in credit supply in the long run, as a result of which the turnover rate will increase. If the central bank does not quickly remove the surplus money from the economic system, asset inflation will turn into consumer price inflation in this phase. The effect is therefore that the surplus money initially boosts asset prices and subsequently credit supply. There are economic situations in which this does not work. Japan is a case in point (over the last three decades).

Extra liquidity created by the Fed did not lead to higher inflation due to a declining money velocity

Source: Refinitiv Datastream/ECR Research

Helicopter money

In most cases, however, there is a way to rapidly increase the turnover rate in a crisis. This can be done by allowing the government to raise its deficits rapidly. At the same time, money creation should be stepped up considerably – preferably by having government bonds bought directly by the central bank and having them financed with money created by the central bank. This should be done to a far greater extent compared to actions taken following the credit crisis. This basically comes down to helicopter money. This means that ‘free’ money is distributed to the population. People will soon start spending this money, which will improve the economy and – after some time – credit supply will receive a boost. This is far more the case now.

As long as the lockdown persists, people will not spend much, and this will probably continue for some time. However, if the combination of a large public deficit and a great deal of money creation persists, the economy will gradually be boosted, especially if lockdowns are gradually removed. When this happens, the central bank could, in theory, remove money from the economic system and the government could reduce its deficits. In this case, inflation stays under control.

However, in practise this won’t happen any time soon. This is because the economy will still fall back, deflation will occur, and a negative deflationary spiral will be evident before long in this scenario. A far more appealing alternative – which has generally been opted for throughout history – is therefore to keep money flowing and to allow inflation to rise. This has the great advantage that nominal – rather than real – incomes of companies and individuals rise more rapidly, which makes it increasingly easy to meet interest and repayment obligations on old loans. The disadvantage is that inflation causes all sorts of misallocation of capital, as a result of which productivity declines to ever lower levels. Interest rates will rise in tandem with inflation. The former is a longer-term problem, while the latter can be delayed by the central bank for some time.

End of an era

We believe that it will take several years for the economies to really overcome the current coronavirus shock. The deflationary pressure will certainly be high at the beginning of this period. However, an inflationary policy will basically be pursued. This will gradually come to the surface, and we believe that it will increasingly shape inflation expectations and long-term interest rates in the decade ahead. This will create a fundamentally different climate for companies and investors compared to the one to which they have become accustomed over the last 30 years.