Companies are increasingly suffering from geopolitical developments. A survey by global insurer WTW found that, in the last year, over 90% of companies had suffered financial losses due to geopolitical risks; this figure was 35% in the previous year. It is striking (and logical because of the Ukraine war) that 86% of Western European companies indicated that they had suffered losses due to geopolitics, while this applied to ‘only’ a third of North American companies.

While the war between Ukraine and Russia may largely account for the increase in losses, the geopolitical risks are broader and more extensive. Half of the companies surveyed by WTW therefore assume that deglobalisation will continue strongly, while more than four in ten expect the trend of decoupling to gain (further) momentum.

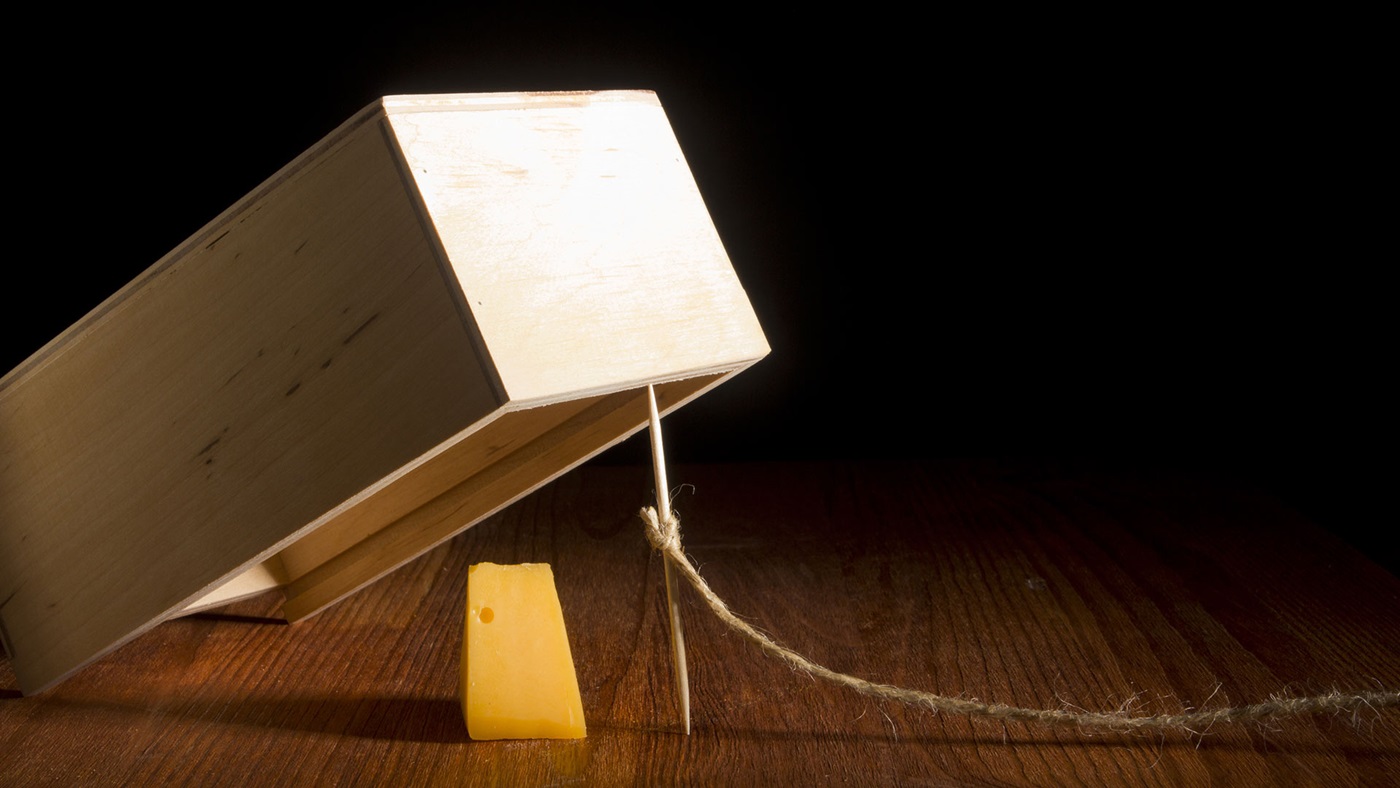

Due to (geo)political shifts, among other factors, three pillars that have propped up the global economy in recent decades are faltering:

- Free trade.

- Governments that increasingly embraced market thinking and gave companies as much free space as possible.

- An almost all-encompassing focus on efficiency by the business community and governments who believed this was fine.

These pillars of global growth came with their fair share of drawbacks. New York Times correspondent Patricia Cohen described the negative sides for the US as follows:

“Television, T-shirts and tacos were cheaper than ever, but many essentials like healthcare, housing and higher education were increasingly out of reach.”

However, this trend of (out-of-control) deglobalisation and market thinking has been abruptly slowed down by, among other factors, the corona crisis, the Ukraine war and the rise of China. Professor of International Relations Henry Farrell argues that “the story of the international economy today is that geopolitics is gobbling up hyperglobalisation.”

The Chinese advance and the associated tensions with the US and its allies are undoubtedly the global political development that will most affect the global economy over the next few years – if only because America and China are by far the two largest economies in the world and China has accounted for roughly a quarter of the world’s economic growth over the last two decades.

In recent years, relations between Beijing and Washington have cooled well below freezing point with, for example, the launch of a trade war under Donald Trump, China cutting off direct military communications following Democratic figurehead Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan and the shooting down of the Chinese spy balloon that flew over American soil. Visits by US Secretary of State Antony Blinken – during which he also spoke with Chinese leader Xi Jinping – and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen seemed to clear the air somewhat.

However, the underlying sources of tension continue to amply fuel clashes and discord. For many issues, a compromise between Beijing and Washington seems very far away: Taiwan, the Ukraine war, technology, military activities in the Pacific, but also on Cuba, for example… These are all examples where there is unlikely to be much rapprochement between the two in the short to medium term.

In addition, until not so long ago, (very) high economic growth in America and especially in China was able to partly ‘flatten’ the competition and struggle between the two, in the sense that both countries benefitted from the design of the international economy and the political-economic system and were therefore not very keen on jeopardising this system; the pie got bigger and bigger and they both got bigger pieces (where the extra pie and whipped cream largely ended up in China’s stomach, for that matter).

The US economy and US politics however, are running up against limits and obstacles that partly result from the design of the international political and economic order. The competitiveness of the US is crumbling, debts continue to increase (for the next ten years, a budget deficit of at least 5% is forecast every year), and nowhere near everyone benefits from America’s enormous power.

Child poverty in America, for example, is twice as high as in Germany and South Korea, among other countries. Over 10% of Americans live below the US poverty line. And in 2018, over five million Americans had to make do with less than US$4 a day (the equivalent of the figure used for poverty in developing countries).

Chinese growth has weakened considerably compared to recent decades, and it is likely to decline further towards 3.5% in the course of the decade. And we perceive quite a few risks of setbacks due to an ageing population, declining returns on investment (ROI) partly because investments are bizarrely high in relation to the total economy, a massive debt burden, geopolitical tensions and a brake on innovation due to a progressively authoritarian course of Beijing, among other factors.

These developments mean that it may become more tempting for America, and especially for China, to rearrange the international political and economic order. Meanwhile, China will continue to close the gap with the US and will see increasing opportunities to challenge Washington’s dominance.

Harvard professor Graham Allison introduced the term “Thucydides Trap”, which refers to the theory that when a rising power challenges a ruling power, there will be an increased risk of conflict and war. He bases this insight on the work of the Greek historian Thucydides, who identified a pattern of conflict between rising and incumbent powers throughout history. Allison found that among 16 situations in the last five centuries in which the ruling power was challenged, 12 ended in war. The growing rivalry and tensions between the US and China therefore pose a considerable risk of conflict, with the very dark possibility of a direct military confrontation between two nuclear powers.

Yet, in our view the most likely scenario – in one of our recent research reports for our clients we outlined four scenarios – is still not all-out war but increasing trade and other conflicts and further decoupling between the two countries. Other Western countries will join the US in restricting trade with China, while China will stimulate its economy by placing greater emphasis on domestic consumption and trade with friendly regimes. While Brussels and Washington are currently insisting on derisking in particular – by reducing dependence on China and by becoming less dependent anyway on the supply of essential commodities and products by one or more countries – this scenario will see derisking alternating with decoupling, and there will be more bloc formation in the political, financial, economic and technological fields.

Both America and China will barely attempt to address the underlying causes of their animosity, but they will also be very reluctant to escalate their rivalry given the devastating consequences this will have.