In a recent interview, Alexander Foltin, Treasurer at European chip maker Infineon, talked about his treasury priorities.

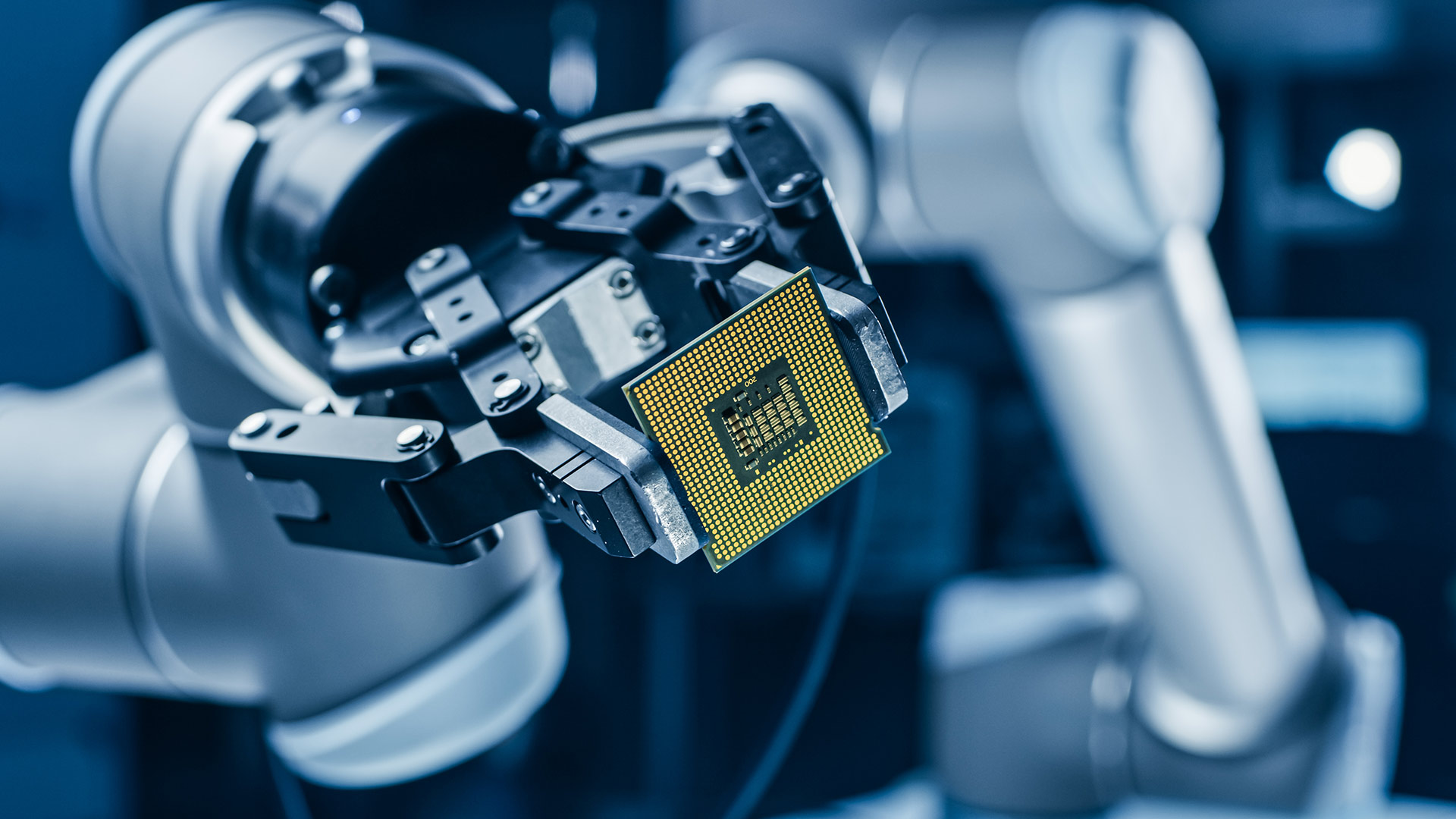

Semiconductors, the brains of all modern electronics from cars and phones to new technology like the IofT and strategic 5G networks, have rarely seen such demand. Behind the scenes, treasury and finance teams provide these strategic companies with complex supply chains, with the financial solutions they need to thrive. In a recent interview, Alexander Foltin, Treasurer at European chip maker Infineon, talked about his treasury priorities.

Keeping up with the competition and ensuring his treasury always has enough on hand to finance growth has put liquidity centre stage. “We have to be able to find the financial means of supporting our growth track,” says Foltin. “We would never bring cash down to bare operating levels. We want to have the financial freedom, especially through cycles and down phases, to proactively invest.”

His other treasury failsafe is easy access to the financial markets and a strong investment grade credit rating. Arranging the financing for the company’s 2019 €9bn purchase of US rival Cypress Semiconductor proved the credit rating’s worth.

Financing came via a final mix of one third equity and two thirds debt spanning two straight capital raises, a hybrid bond placement, a jumbo euro bond and one US private placement in a strategy carefully choreographed to keep the rating agency (S&P Global) happy, despite the unprecedented size of the deal – half of Infineon’s market cap. “We spent a lot of time with the rating agency upfront, presenting financing scenarios to ensure our target equity debt mix would safeguard the company as investment grade.”

Although the rating slipped from BBB flat to BBB – when the deal closed, it was still investment grade. Since then, S&P; has bestowed a positive outlook on the company, indicating a road to a potential return to BBB flat. This has ensured the door was always left open to the right kind of investors at the right price, he says. “If you are sub investment grade you run the risk of markets being closed or unavailable. We have funded ourselves up to 2033.” It also meant the company could access the ECB’s bond buying programme, set up to support investment grade companies with stable funding through the pandemic.

The process also marked another coming of age in today’s volatile and challenging semiconductor market. Prior to the Cypress deal, Infineon didn’t have an established set of core banks providing an RCF. In a quid pro quo, the group of banks advising on the deal committed funding lines in return for the M&A advisory mandate. “They had to chip in and put their money where their mouth was, guaranteeing to underwrite the initial transaction,” he said.

Since then, the company has syndicated out to 20 national and global institutions, initially providing committed financing across a short-term bridge facility as well as term loans out to 2024. Take-out transactions were all allocated competitively. “Normally you have initial underwriters who take the largest piece of cake, then financing is pre-allocated according to ticket sizes in the syndication,” he explains. “Following the syndication, we had all our banks on an equal footing so that whenever a refinancing came up, they could compete equally.” Although the process is more laborious for banks and treasury, it assures Infineon gets “the best service” from “highly motivated banks,” giving them a chance to “prove their worth.”

It’s just the kind of competitive, level playing field that plays to banks’ individual strengths that he wants in the global chip market. And one of the reasons he questions if investing billions in more manufacturing capabilities in Europe to reduce dependency on highly skilled Asian contract manufacturers, would ultimately benefit. The EU plans to transform its semiconductor manufacturing capabilities, aiming to double its share of the global chip market by 2030. Most recently Intel has placed itself at the centre of those ambitions, proposing to build a brand new US$20bn semiconductor factory on the continent. While in the US plans to beef up the domestic industry have been enshrined into a new bill “Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors for America Act,” or CHIPS, outlining plans to create a US$10bn federal grant, investment tax credits and a variety of research and development funds. Yet Foltin isn’t convinced that getting into a spending race is viable, questioning if the EU can match government incentives elsewhere. “We welcome support for a road map for the European industry, but we need sensible, intermediate steps on route to getting there.”