History is littered with examples of the transformational power of commodities. The Californian Gold Rush of the 19th century, for example, converted a handful of small frontier settlements on the US West Coast into big cities as hundreds of thousands of people travelled from around the world to make their fortune.

Today, crude oil, nicknamed ‘black gold’, is the world’s most prominent commodity. Oil is the commodity of the modern age and plays a vital role in every part of an industrialised economy. It can be used to generate heat, fuel vehicles and manufacture nearly all chemical products. As such, its transformational power has surpassed that of gold and any other commodity before it.

Oil and gold fit perfectly into the dictionary definition of a commodity: a raw material that can be bought or sold, at any time, anywhere in the world. As a rule, commodities are uniform in nature – in other words, you should not easily be able to tell who or where it has come from by its look, taste, feel or smell. A product (made out of commodities) on the other hand can usually be identified as being created by a certain company.

Commodities are big business, and so is financing them. To the point where the market has developed its own nuanced ways of financing players in the commodities market.

Heavy users

In some way, all companies are users of commodities, either directly or indirectly. But not all companies are users of commodities finance, because although they might purchase commodities such as fuel, they do not then produce something from this which is a commodity. By using the fuel to power an airplane or oil tanker the commodity is being transformed into a product or a service. Once the commodity is in the hands of these companies, who are end-consumers, it can no longer be banked as a commodity and this is where commodities finance slips away.

The traditional target market for commodities finance can therefore be broken down into three categories:

- Commodity trading firms such as Vitol, Glencore and Cargill.

- Producers of commodities, for example: Saudi Aramco, Adecoagro and BHP Billiton.

- Processing companies, such as: Reliance Industries, Sinopec and ArcelorMittal.

Built to fit

The unique nature of the commodities market, in respect to the size of the deals, the need to often raise financing quickly, the risk levels and its cross-border nature, has seen it develop its own nuanced approach to financing. This is commonly referred to as structured financing.

Structured financing is different from traditional trade financing because the lender takes security (this can vary from the commodity itself, to contracts, shipping documents etc) in return for the cash. In doing so, the credit risk is removed for companies along the supply chain, because the lender (often a bank) is the trusted entity in the transaction who will guarantee payment to the producer/seller.

This is important in the commodities business because many of the companies involved are not rated in their own right, or are operating in countries with below average ratings, and therefore find it difficult to access affordable financing. Other advantages of this arrangement include:

- Working capital is freed up – this benefits the entire supply chain and allows the flow of commodities and cash to continue.

- Commodities are very liquid and banks are therefore willing to lend against unprocessed goods because they can be liquidated should need be.

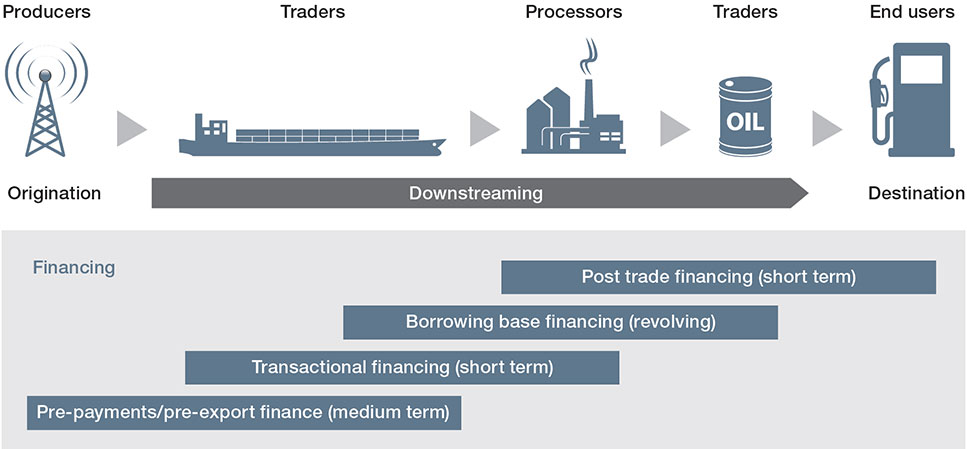

Within the scope of structured finance there are several different key methods of financing during the commodities lifecycle (see Chart 1). And many of the products that are used in these methods of financing are those typically found in traditional trade finance.

Chart 1: Different stages of financing

Source: Galena Asset Management, 2013

Pre-export finance

Pre-export finance is often raised against the producer’s projected future export revenues, but it can also be based on existing orders along with the buyer’s payment risk. In most cases, these deals are short-to-medium term, with a tenor between one and five years and can be amended or restarted during this period.

In a typical pre-export finance agreement, the funds will be provided by an individual lender or a syndicate for all manner of working capital reasons, including:

- The purchase of raw materials.

- Manufacturing and production costs.

- Transportation and storage costs.

- Sales and admin expenses.

In a pre-export structure, the loan is secured by a security assignment of the relevant delivery contracts between the producer and ‘offtakers’, and the receivables generated under those contracts following the delivery and sale of the relevant goods. Also, there will be a charge over a collection account (belonging to the producer) into which the proceeds of the sale are paid. After deductions for debt service, excess funds are made available to the producer. It is worth noting that there a number of ways a structure can be enhanced, including introducing hedging products to protect against commodity price fluctuations and interest rates.

The overall benefits of using a pre-export financing solution include:

- The ability to enhance liquidity and produce goods.

- Lower interest rates in different countries can be leveraged.

- The solution is resilient to country default or capital controls.

Commodities financing: a short history

Just like any corporate, commodity producers, processors and traders require financing to ensure that the tools which help build and maintain industrialised economies keep coming. This vital function is, on the whole, provided by the banks, primarily the large European, Japanese and American banks, who have been active in the commodities market for centuries.

But it is an evolving relationship. Original financiers of commodities would have done so by issuing letters of credit to the commodities firms which were secured against the commodity. This relationship largely existed unchanged until the 1980s, and the deregulation of the financial services industry. This provided the banks with an opportunity to explore new avenues of revenue – primarily becoming brokers and market makers in the world’s largest commodities exchanges. In the 1990s, the relationship further changed, as commercial banks expanded into the commodities trading business as a way to capitalise and meet new regulatory requirements, going in direct competition with the companies they had been financing.

While this proved a prosperous adventure for the banks, the onset of the global financial crisis in 2008 and the regulatory changes since, have again reversed the banks’ relationship with the commodities world. A large number of banks around the globe, such as Barclays and J.P. Morgan, have sold off their commodities trading businesses and returned to their original remit of providing financing for the commodities sector.

Prepayment financing

Prepayment financing is similar to pre-export financing in many aspects. However, in these arrangements the producer receives the cash directly from an offtaker as an advance payment under the export contract. Lenders can fund the offtaker and share the risk of non-performance by the producer.

The typical tenor of such a facility can vary between a few months and up to five years for the strongest producers. In regard to the security used during the deal, this includes a security assignment by the offtaker of its rights under the export contract with the producer, including the right to have the prepayment advance repaid.

In the case of pre-export or prepayment finance, the primary risk is placed in the producer’s ability to deliver the commodity. To the extent lenders are comfortable with the performance risk of the producer, the offtaker who is extending the finance, can account for this line of credit as ‘credit limit neutral’.

Aside from this, other benefits include:

- The ability for the producer to access credit from lenders that do not bank the producer directly.

- Buyers can negotiate term supply contacts in return for the provision of finance.

- Mitigation of transfer risk as funds are paid into an offshore account as shipments are made.

- Legally resilient against country default.

Borrowing base financing

The final key financing structure related to commodities is borrowing base financing. This is a structure unique to commodities and is used primarily by traders and processing companies. In these arrangements the borrower’s assets – typically accounts receivables or commodity type inventories – are used as security. Once the security is in place, the solution is flexible, an upper credit limit will be agreed from the onset, but the actual amount of financing will be directly correlated to the value of the pledged commodities or receivables. Borrowers can therefore access more financing as commodity prices increase and their needs change. These facilities are revolving in tenor and typically exist for one to two years, after which they are extended at the discretion of the lenders.

To calculate the financing that can be offered to a borrower against their collateral, the lender will carry out the following calculation: the net value of the accounts receivable (accounts receivable less deductions such as those which are overdue, doubtful, or which can be contested) plus the net value of the goods (goods less deductions such as trade payables). This represents the total collateral value against which haircuts will be applied to determine the amount available for funding.

The benefits of such an agreement include:

- Continuity of a credit line that fluctuates with the commodity price and hence the financing requirements.

- Reduced cost and better access to funding through collateral cover.

Is the well running dry?

There are some commentators in the commodities space who argue that traditional commodities finance provided by major global banks is dying. It is an understandable argument when we look at the major banks’ relationship with commodities post-crisis. As mentioned, many have pulled the plug on their commodities trading business, and following the crisis banks reduced their lending quotas because of their reduced access to dollar funding and the scarcity of balance sheet assets.

Since the crisis, regulatory pressure from Basel III has further added to the argument. Banks are having to focus more and more on risk weighted assets and ensuring that these are used efficiently. We are also seeing some of the world’s global banks realign and pull out of countries and regions where they don’t have material presence and scale. Finally, many commodity financiers have become slow to react to the needs of the market in respect to extending finance as the internal process around approving these is now more complicated.

The stats also make a compelling argument. According to the Bank for International Settlements, which published a report which stated that before the crisis, 80% of global commodities trade financing was provided by banks, and primarily those in Europe. But more recently this number has shrunk to 50%.

As a result of these changes, many firms in the commodities world have already seen their costs of financing increase.

There is some relief, however, provided by the cyclical nature of the commodities business. In times when commodities prices are low, as we have seen with oil this year, there is less for banks to finance. In fact there was almost 50% less oil business to finance since the summer of 2014, but on the whole, lines of credit were unchanged. This means banks have to process double the amount of transactions to make the same revenues, which puts popular borrowers in a stronger position when looking to achieve financing.

Despite this, there is a shortage of bank financing for some commodities players, especially for mid-sized commodities firms in emerging markets. In many cases, the deals being made by these companies are too small and also the ‘know your customer’ processes are often so heavy that it makes it more challenging for the bank to onboard the client.

There is some relief for those companies that are struggling to find financing in the post-crisis world, namely smaller regional and local banks. Over recent years a number of banks from Asia, Africa, the Middle East and Latin America have begun to be active in the market as both providers of short-term financing and as part of RCFs. The caveat is that these banks are primarily looking to support firms that are providing growth to their country or region, a bank in Brazil for example will offer financing to top firms only in Europe, but may look to help smaller firms in its own country – something which has been called the regionalisation of trade finance. These firms are also in the business of cross-selling off the back of their financing.

Since the crisis, commodities firms have also looked to diversify their funding sources themselves and reduce their reliance on traditional bank financing. Some of these firms have, for example, further delved into the capital markets. A handful have taken this even further and established their own asset management business as a way to take advantage of the different types of investors looking to pump liquidity into the market.

There are other sources that commodities firms can tap, such as private equity firms who are looking to provide financing in areas that have always been out of the scope for banks – agriculture in emerging markets, for example. Yet, these firms normally have a high cost of capital and demand higher yields to justify their involvement.

Whether these developments point to traditional trade financing dying remains a topic up for debate, and this may just be the argument used by those no longer able to compete in the space. But one thing that does seem certain is that post-crisis commodities financing has changed for good.

Thanks to Kris Van Broekhoven, Global Head of Commodity Trade Finance at Citi for his help in providing information towards this article.