In the current global economic environment, corporates are finding the task of capital preservation increasingly challenging. For corporates operating in tightly-controlled Asian markets the decision as to where to invest surplus cash is often even more complex. In this article, we examine these and some of the other issues surrounding short-term investments currently facing the corporate treasurer.

Generating profit is not usually the concern of the corporate treasurer. Treasury departments are cost centres, their function limited to managing accounts and, where possible, controlling the financial risks stemming from the company’s operations.

So, why would a non-financial corporate decide to invest surplus capital? The reason in most cases is the preservation of principle. Particularly in today’s low-interest rate climate, the value of corporate cash deposited with banks is vulnerable to erosion through inflation. Moreover, with the Basel III regulation requiring banks to hold extra capital against deposits, they are becoming more reluctant to hold large sums of surplus cash.

The contradiction lies in that companies in Asia, as in Europe and North America, are growing more cash-rich. For example, recent data compiled by Thomson Reuters indicates that two China-listed companies, China Life Insurance Company and Ping An Insurance Group, have cash balances of $82 billion and $38 billion respectively. But for companies such as these, deciding what to do with that money can be even more complex when you factor in the restrictive monetary policies at play in China and a number of other countries in the region.

Investment priorities

A corporate’s investment decision-making is usually influenced by three main considerations: security, liquidity and yield. The relative importance of these considerations has always run in that particular order. However, in recent years the importance of yield has diminished even further in the eyes of the corporate treasurer.

Following a financial crisis which plunged the global economy into a downturn, the like of which we have not seen since the 1930s, the growing risk aversion taking hold of companies should not come as a surprise to anyone. For treasurers investing in this perilous environment, security and liquidity have become paramount. The focus, therefore, will be on developing an investment strategy that produces the optimal risk-adjusted return.

Below is a summary of the key short-term investments companies may use to achieve this objective. These include:

- Money market funds (MMFS).

- Exchange traded funds (ETFs).

- Certificates of deposit (CDs).

- Treasury bills (T-bills).

- Repurchase agreements (repos).

MMFs

With strong security and high liquidity, MMFs remain a popular option for corporate investors. This was reflected in a recent survey by Fitch Ratings, according to which 50% of corporate treasury professionals use MMFs, making the funds their next preferred investment vehicle after bank deposits.

The funds are typically used by corporates as an alternative to bank deposits, one which offers the investor higher yield but without sacrificing liquidity. There are significant differences between the two. MMFs are asset management products where providers secure yield for their clients through the purchase of a narrow range of highly-rated assets. Secondly, MMFs are not guaranteed, whereas bank deposits are. In fact, some critics argue that their ultra-safe, deposit-like appearance often masks a deep-rooted structural instability.

The risk for investors is that there will be a run on the funds or, to put it another way, too many investors seek to redeem at the same time. As a consequence, the fund may struggle to liquidate its assets quickly enough, causing the fund’s Net Asset Value (NAV) to fall below the prescribed $1 baseline, something which is referred to in the industry as ‘breaking the buck’.

The last time an event of this nature occurred was in 2008, when the reserve primary fund collapsed as investors all rushed to the door over concerns about the fund’s exposure to Lehman Brothers. Such events are uncommon, however. From the industry’s beginnings in 1971 until the financial crisis, only three MMFs ever broke the buck – a figure which some critics argue might be higher without the discretionary sponsor capital many are able to draw upon in times of market stress to preserve their constant NAVs (CNAVs).

No wonder then that the same Fitch Ratings survey found that CNAV investors tend to place great emphasis on the importance of the sponsor when choosing a fund to invest in. Other factors commonly taken into consideration include the credit/risk quality – with AAA being the preference – and the funds past performance.

The industry is now more tightly regulated than it was prior to the financial crisis, and there is also the prospect of further regulation on the horizon. One proposal, recently mooted by the European Systematic Risk Board (ESRB), is proving particularly contentious. The ESRB recommended in a recent review, that there should be a mandatory conversion of all CNAV funds to floating NAVs, on the grounds that this would help to reduce the ‘first mover advantage’ believed to be a cause of runs on funds. But this, some say, may diminish the utility of MMFs for corporate investors, who largely prefer CNAV because of the simpler tax and accounting treatment.

In recent years, MMFs have become an increasingly popular alternative to bank deposits for companies operating in China. In the past, these companies were rather limited in their options for managing liquidity. Both yields and tenors of bank deposits are regulated in the Chinese market by the People’s Bank of China (PBoC), and rates are often lower than they would be if aligned to real market yields.

The introduction of MMFs has provided an attractive alternative for investors. Most of the funds currently flourishing in China follow guidelines set by the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC), which are considered to be much tighter than current international guidelines.

ETFs

Amid all the uncertainty regarding the regulatory changes to MMFs now looming on the horizon, corporate investors may wish to consider short-duration bond ETFs. A degree of caution should be observed as these types of fund typically assume greater levels of risk, compared with traditional MMFs, in order to secure marginally higher yields. Another big difference is that the shares of short-duration ETFs, unlike CNAV MMFs, fluctuate during trading hours – much in the same way as stock prices.

Again, these could be an option a corporate operating in China may wish to consider. In China, ETFs such as FXI, the iShares FTSE/Xinhua China 25 Index ETF, invest in the equity prices of China-based companies. Similar to MMFs, the funds reduce risk through diversification, allowing investors to gain exposure to a number of different sectors such as banking, construction, energy and communications.

CDs

CDs are debt instruments issued by banks and other financial institutions which are widely used by corporates in place of clean, fixed bank deposits. In exchange for keeping the money on deposit for an agreed fixed-term, unlike a traditional bank deposit which can be withdrawn at will, a set rate of interest is paid to the investor. The rate that is offered is generally aligned to the maturity of the asset, which can range from only a few weeks to several years.

As is the case with any tradable instrument, the secondary market value can be impacted by investor sentiment. This is the main source of risk for corporate investors not wishing to hold on to the CD until maturity. It means that negative news concerning the issuing bank could, potentially, result in a dampening of demand for the product.

T-bills

T-bills are a short-term money market security issued by national monetary authorities. The probability of a sovereign default is considered to be very low – recent events in Argentina notwithstanding – so T-bills are often the first point of refuge for investors during periods of market stress. The main disadvantage for investors in these securities is that yields are often minimal at best. For example, US T-bills have traded at negative yields in recent years and are currently close to zero.

Repos

Repos involve the sale of securities such as corporate or government bonds tied to a commitment from the seller to buy them back at a later date. Investing in repos can sometimes prove complex. Such securities are therefore more suitable for large corporations with very sophisticated treasury departments able to handle the administrative burden.

In Chinese repo agreements, the collateral posted is typically a government or corporate bond. Repos cannot be entered into by foreign-invested enterprises. The yields on repos or short-term government debt are generally more attractive than short-term deposit rates.

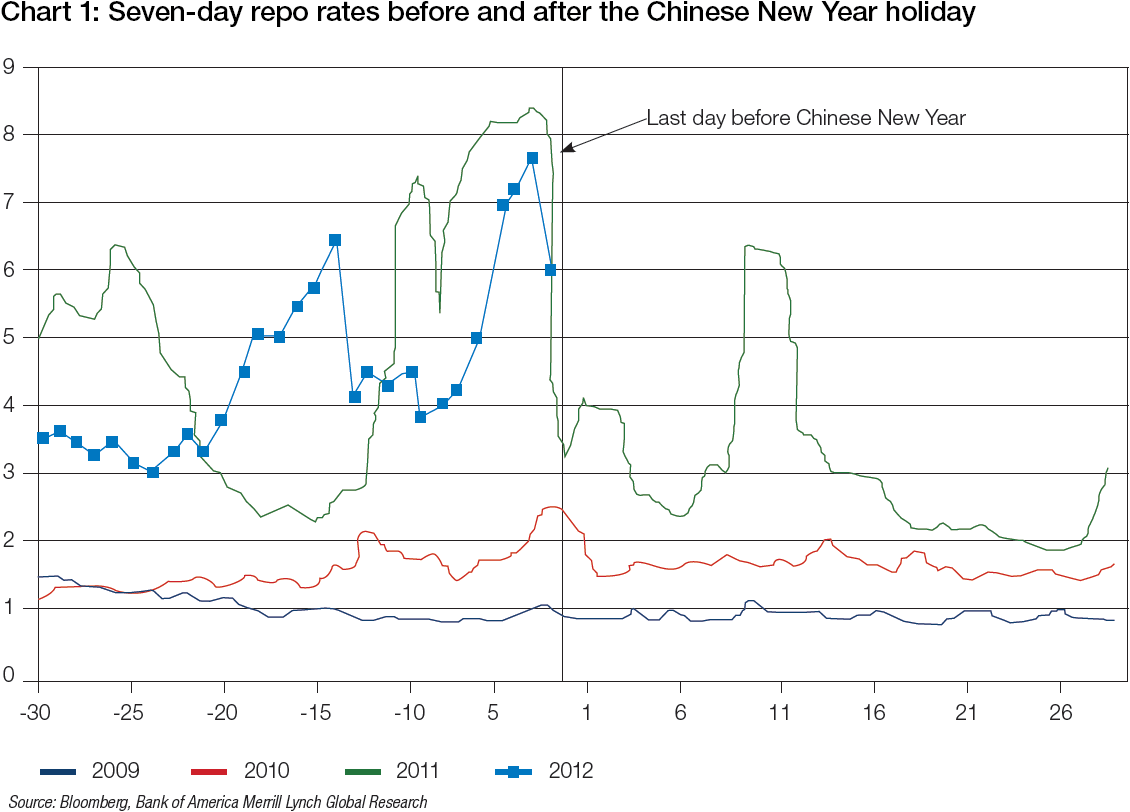

A good time to tap the repo market is in the run-up to the Chinese New Year when banks are often short on cash as demand rises (see Chart 1). Again, when a big IPO comes to the market, exchange repo rates can be extremely high as investors rush to find ready cash. There is undoubtedly a correlation between hot stock issuance and inflated exchange repo rates. The seven-day bond repurchase rate closed at a three-year high of 7.69 at the start of 2013.

Chart 1: Seven-day repo rates before and after the Chinese New Year holiday

Source: Bloomberg, Bank of America Merrill Lynch Global Research

Conclusion

The present economic climate poses a number of challenges for the corporate investor. Banks’ appetite for deposits is diminishing as a result of new liquidity regulations such as Basel III. However, with interest rates near record lows across a large number of Western and Asian markets, low-risk returns through investment vehicles such as MMFs are not easy to come by either.

The current scarcity of yield should not be the over-riding concern. New risks to global financial stability are emerging, even before the problems left by the last financial crisis have yet to be fully resolved. For corporates operating in this uncertain environment, security and liquidity will certainly be the main factors for consideration when it comes to depositing their cash, with yield now nothing more than an afterthought.

Are there ways to secure better returns without necessarily forsaking yield? There has been talk recently on the prospect of ultrashort-term ETFs being used in lieu of MMFs, should the proposed regulatory changes feared by the industry be introduced. The aim of these funds is similar to MMFs: preservation of capital. A note of caution, however – the risks assumed by investors in these funds may be greater than the norm in the MMF market. In addition, since ETF shares float and their prices are not fixed like CNAV MMFs, principle can be lost.

Finally, it is also important to remember that when it comes to returns on balances, yield is not the only factor. In recent years, banks have been developing new products – such as accounts which allow clients to use their operating balances to manage down their fees and increase their margins – which should certainly be of interest to the corporate treasurer, providing that is, they do not disappear in the wake of Basel III.