The low interest rate environment has been a dominant theme for the cash manager and corporate treasurer for several years. We look at the outlook for global growth, inflation, interest rates, and what to look for when evaluating investment options for longer-term cash balances.

Ian Lloyd

Head of Global Liquidity Distribution, Legal & General Investment Management

Legal & General Investment Management is one of Europe’s largest asset managers and a major global investor, with total assets of £757bn1. We work with a wide range of global clients, including pension schemes, sovereign wealth funds, fund distributors and retail investors. Throughout the past 40 years we have built our business through understanding what matters most to our clients and transforming this insight into valuable, accessible investment products and solutions. We provide investment expertise across the full spectrum of asset classes including fixed income, equities, commercial property and cash. Our capabilities range from index-tracking and active strategies to liquidity management and liability-based risk management solutions.

A difficult backdrop

It has now been over seven years since the Bank of England Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) cut rates to the current historic low of 0.5%, and despite low unemployment and recruitment surveys indicating a tightening of the labour market, since early 2016 forward rates have been suggesting an unchanged or lower UK base rate for a further three years.

Sterling cash managers have been spared negative rates (for the time being at least), but they have nevertheless had to deal with the equivalent economic effect, as deposit rates have failed to compensate for the erosion of inflation. Furthermore, changes to bank regulation discouraging reliance on short-term funding, as well as an overall reduction of short-term wholesale funding needs, mean that even when policy rates begin to rise, the return available on short-term cash will be structurally lower.

It is little surprise then that many corporate treasurers have been keen to explore how they can generate improved returns on their cash. How should the corporate treasurer interpret the interest rate outlook, and what options are available to mitigate the low return environment?

The macro picture

Our view is that growth and inflation (and therefore interest rates) will struggle to rebound. This is based on what we call the ‘four Ds’ – namely debt, deficits, demographics and deflation – which we expect to dominate the macro backdrop, keeping base rates and government bond yields subdued for the foreseeable future.

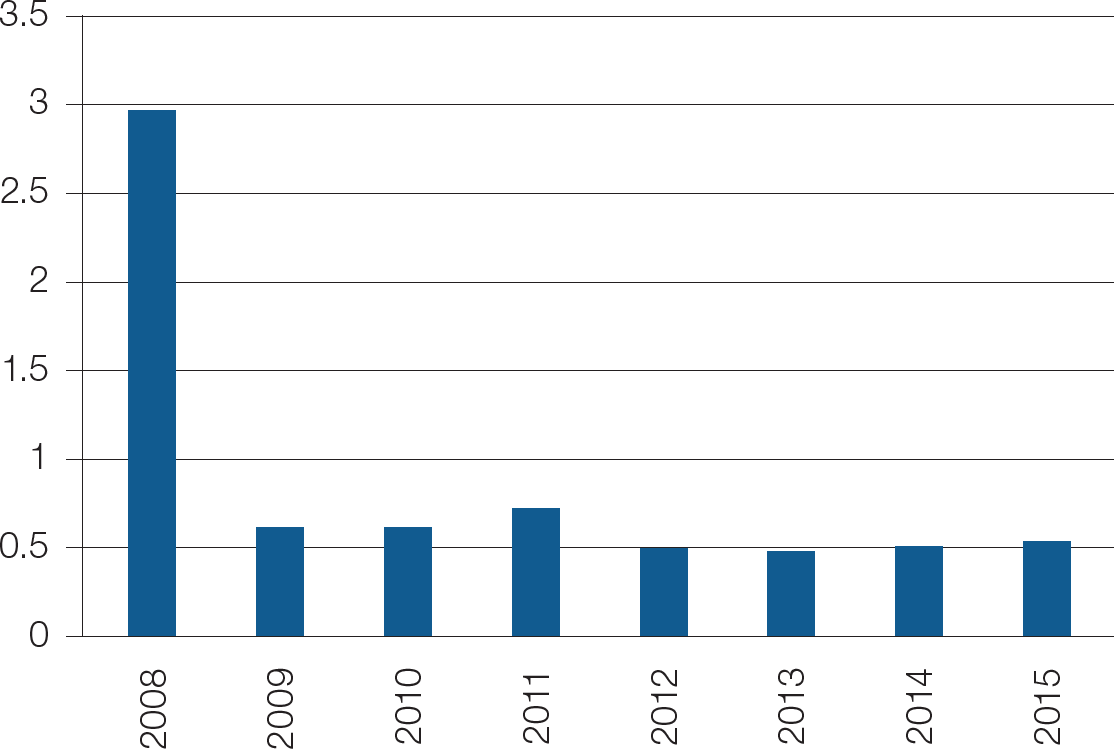

Source: LGIM, Bloomberg, based on generic two-year government yields since January 2008

The first D is debt. If the ratio of debt to economic activity (GDP) rises for a prolonged period of time – as it has for some three decades in the case of the US – then the assets have not been able to generate the return to pay for the debt. In other words, capital has been misallocated, weighing on growth, discouraging future investment and sowing the seeds of social inequality.

The second D is the typical government response to a perceived cyclical downturn in the hope that growth will eventually improve deficits. Governments are promising their populations all sorts of future benefits, but have very little chance of following through on all of these commitments. In the meantime, they run deficits, thereby building up more debt and crowding out potentially more productive private sector activity.

Debt and deficits are real problems that are ultimately fixable by policymakers. However, the third D, demographics, is harder to influence. The problems faced by many developed countries are well known, particularly Japan and a number of ageing European countries. But perhaps the most important country in terms of global growth is China, and here the one child policy will weigh on demographics for a number of years to come.

It must be a great surprise to many people, notably the global central banking community, that despite seven years of zero interest rates and trillions of dollars of quantitative easing (QE), our final D, deflation, continues to threaten a number of countries. We believe the cause of this to be the structural problems outlined earlier.

The regulatory picture

Regulatory changes that have their roots in the financial crisis are also depressing returns for cash investors. In short, regulators wanted to make the banking system more secure by reducing its reliance on short-term funding.

As a result, Basel III regulations therefore state that banks taking in large deposits (such as those from large money market investors or corporate treasurers) must hold high quality liquid assets – typically central bank reserves or government bonds. In effect, this makes short-term wholesale funding more expensive for banks, reducing the return they offer for this type of financing.

The alternatives

Typical approaches to generating an increased return on cash include:

Direct investing

Corporate treasurers can look to manage a portfolio of these assets where they have the appropriate internal credit research and trading resource available. A higher return can be generated, but potentially at the expense of capital preservation should the anticipated investment horizon change at short notice.

Liquidity plus or ultra-short bond funds

The more developed US money market saw significant allocations into ultra-short or liquidity plus funds in the years immediately following the implementation of ultra-low policy rates. There has been significant interest in these products in the UK as well, despite the bumpy performance of some funds during the financial crisis.

Separate accounts

Separate accounts enable investors to have a professionally managed portfolio tailored to their specific return requirements and risk appetite. In practice however, separately managed account guidelines often deviate little from standard pooled funds (eg AAA short-term money market fund), and therefore do not offer much in terms of increased return while sacrificing the efficiency of liquidity associated with a pooled fund. Separate accounts are useful where investors have particular risk and return profiles and where cash flows are predictable, or the investor is willing to sacrifice some return to meet unexpected cash requirements.

Source: IMMFA, based on 30 day gross returns at year end

A closer look at liquidity plus

We believe that the AAA short-term money market fund provides the best return outcome when also wanting to meet the principle objectives of daily stability of capital and same-day access.

For longer-term cash allocations however, where price stability may be a six or 12 month objective, the liquidity plus fund can be a useful addition to the cash management tool kit. That said, while the AAA short-term money market fund product is well established and understood, there can be significant differences between the liquidity plus, ultra-short and short-term bond options available.

Different approaches will suit different investment horizons and risk appetites. We believe that there are five key considerations for corporate treasurers when evaluating ultra-short or liquidity plus funds:

- The investment horizon, and how the fund is designed to target capital preservation within that context.

- The fund rating. While the bond fund rating assigned to a liquidity plus fund is less prescriptive than a short-term money market fund rating, these can provide a guide of overall credit quality and sensitivity to market risk. A bond fund rating will typically consist of a credit and market sensitivity component.

- The investment capability of the provider, including credit research resource, and where the product fits within a range of investment products offered.

- The underlying investments within the fund, particularly important with regard to structured finance, where the maturities of underlying loans can be very long dated (for instance mortgages) and perhaps therefore not consistent with a shorter-term investment horizon.

- How return is generated. A short-term money market fund (ie liquidity fund) generates return over cash through a combination of credit and duration risk, albeit in a very controlled way (eg maximum 60 day weighted average maturity and 90 day weighted average life). A liquidity plus fund has more flexibility, so you should be comfortable with how risk is allocated and managed.

Footnotes

- as at 31st December 2015, including derivative positions and advisory assets.