Despite the record cash reserves being held by large corporates, securing the right balance of external funding remains a key concern for most treasurers. But with banks constrained by regulation, and the continuing low-yield environment showing no signs of abating, which is the best option – bank loans or bonds? Or perhaps an alternative to these traditional sources?

Corporates, at least in Europe, are sitting on more cash than they ever have before. In September 2014, companies in the EMEA region held cash reserves of nearly €1 trillion, according to research published by Deloitte. Surely, then, most corporates don’t need to worry about their funding mix – that is, how their sources of funding break down into equity, bonds, and bank lending – why don’t they just finance projects, acquisitions and growth internally?

However, delve into the figures a bit deeper and you realise it is not quite as simple as that. Deloitte also found that 75% of cash reserves in EMEA are held by just 17% of corporates in the region. And this trend broadly replicates corporate cash concentration worldwide, with approximately a third of companies holding 80% of the world’s $3.5 trillion corporate cash reserves.

A key driver of this hoarding is caution. After all, in recent years, many corporates have become wary of finding themselves short of liquidity, so have often refrained from undergoing significant or transformational change. This has led to event-driven financing being subdued.

“Since the financial crisis, companies have generally been more conservative in funding themselves,” says Richard King, Head of UK Corporates and Debt Capital Markets at Bank of America Merrill Lynch (BofAML). “They saw what happened during the crisis, with credit markets grinding to a halt, and there has since been an increasing desire among corporates to boost their liquidity, even to the extent where they’re sometimes overfunding themselves.”

Colm Rainey, Head of UK Debt Capital Markets at Citi, concurs that caution is now the name of the game. “There is definitely a higher degree of caution in the market now,” he says. “It is a case of ‘once bitten, twice shy’, but even those who didn’t get bitten in 2007 knew another corporate who did.”

Many corporates are expressing this caution in the way they pre-fund maturities. “In cases where companies know they have got bond or loan maturities coming up, they are tending to pre-fund those maturities earlier,” says BofAML’s King. “In the past they might have waited only 12 months before the maturity, whereas now they’re typically going to the markets and funding them a lot earlier.”

“No one’s getting into trouble with management for being pre-funded, particularly with debt costs as low as they are,” adds Citi’s Rainey. “This caution is permeating organisations. There is a genuine belief in companies – not only from treasurers, but from the board level down, that it’s better to be safe and bear the cost of carry than worry overly about carry and then realise it’s blown up in several months’ time. This is an organisational change – treasurers are being listened to more carefully than they were in the past.”

Monitoring counterparty risk

Amid this mood of caution, counterparty risk monitoring has also come right to the fore. “Pre-financial crisis there were many companies that didn’t even think about the counterparty risk on banks – they thought that, within reason, banks were never going to fail as the majority of the big banks were very highly rated,” says BofAML’s King. “The financial crisis has shown that’s something they absolutely have to think about, as most – if not all – of the banking sector has been downgraded since the crisis.”

Of course, regulation has also played a part in creating this environment. Since the financial crisis, regulation on banks – such as the capital adequacy measures that are part of Basel III – has begun to transform the way they are structured, and to a certain extent, has impinged on their lending activity as well as the buffers they hold. Barclays, for instance, has twice the amount of capital it had pre-crisis and seven times the liquidity. This regulation has had, and will continue to have, an impact on corporate lending activity, acting as a brake on some of the business the banks were able to provide customers in times gone by.

“The banking industry is facing long-term structural changes through regulatory initiatives,” explains Karl Nolson, Head of Debt, Managing Director, Barclays Corporate Banking. “The industry as a whole is certainly benefiting from additional governance as banks are required to put aside significantly more capital for every pound they lend. Therefore, put simply, regulation is likely to act as a floor on loan pricing and an appetite ceiling in terms of the amount of credit that banks will be prepared to provide for customers.”

Despite this caution, and the impact of bank regulation on lending, it is not all doom and gloom in the bank lending market. “That’s not to say that the loan market is not buoyant – banks are keen to lend and indeed prepared to underwrite large loan transactions – as we have seen on a number of occasions this year. However, the majority of loan demand has come from finance teams taking advantage of the lowest cost of debt for a generation and banks being very keen to lend,” says Nolson.

He adds that bank lending should continue to be a key means of providing finance for corporates. “It is important to note that loans still remain a staple source of funding for European businesses: their share of total financing may have fallen since 2008, but volumes have remained far more stable over the past seven years than other types of funding. So, given their inherent flexibility and private nature I expect loans to remain a strategically core funding component for UK and European businesses.”

An alternative route

Banks are not the only ones to provide funding to corporates. A big development that has shifted the corporate funding mix in recent years is the emergence of alternative financing. Banks that have historically provided lending to corporates are no longer just competing with other banks or traditional lenders. Peer-to-peer lenders and challenger banks are providing additional liquidity to smaller businesses, while mid-to-large sized corporates are increasingly looking to non-bank lenders, including lenders in the private equity space. Meanwhile, multinational corporates are increasingly turning to private placement funding.

“The common underlying theme for alternative sources of finance is low interest rates causing investors to search for higher returns by entering new or alternative markets,” says Barclays’s Nolson. “This additional liquidity, or more people investing, is seen in the fall in average Yield-to-Worst for BB-rated high-yield bonds from highs of above 10% in 2011 to current levels of 5% and the volumes of UK non-financial borrowers have risen from $70 billion in 2007 to $101 billion in 2014 to date.”

However, despite the growth in alternative financing, capital market financing remains the biggest alternative to bank lending. “Business is benefiting from a more diversified funding mix – borrowers are presented with highly attractive financing options and this has led to less reliance on traditional bank loans,” says Nolson. “We can see these trends reflected in corporate capital raising in the UK – for instance, in 2007, loans represented 75% of corporate funding, but since then debt capital market and equity capital market funding have made up an increasing share with 30% and 13% of the capital stack in 2014 respectively, with loans therefore making up 56%.” Bonds, therefore, remain crucial for corporates. But could they eclipse bank lending?

Bank to bond shift?

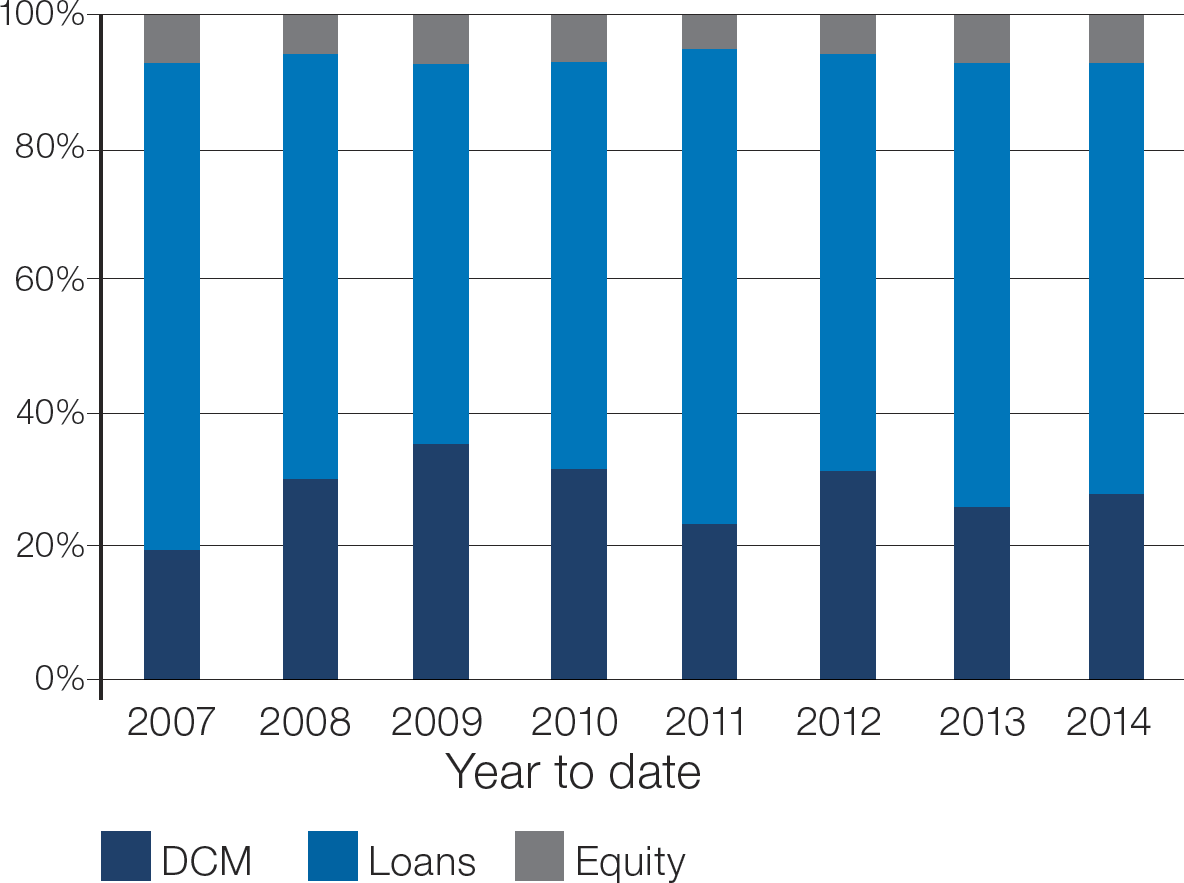

A commonly held view is that corporates in the US are much more reliant on the debt capital markets for their financing than their European counterparts. Indeed, in 2007, around 20% of the corporate funding mix in the US was made up of bonds, compared with just over 10% in the EU (see Charts 1 and 2). However, since then reliance on bonds in both regions has fluctuated, rising in 2009 (to 37% in the US and 43% in the EU), before falling again in 2010 and 2011 (22% and 26% respectively). Interestingly, the debt capital market proportion of the funding mix in the EU has exceeded that in the US for every year since 2011 (in 2014, as of November, the bond percentage was 26% in the US and 38% in Europe).

Chart 1: US Funding mix 2007 – 2014

Source: Dealogic

Besides the challenges in the bank lending market we have already seen, what other drivers are there behind this move into debt capital market financing?

One is the way the bond market has evolved since 2007. “The bond market has significantly matured over the last few years and this development has made it more flexible and accessible for companies,” says BofAML’s King. “The Euro Medium Term Note (EMTN) programme, for example, facilitates the raising of relatively small amounts of money at very different tenors with individual investors or a group of investors on a regular basis. This allows companies to be more targeted and flexible in their financing – they don’t have to go out and raise €1 billion from the bond market; they can raise €100m or €200m via a private placement. The US private placement market has also come into its own over the past few years – it has become incredibly stable, and remained open throughout the crisis, which is not always the case in the public bond market.”

This flexibility helps corporates tailor their funding needs to their specific circumstances, with the competitive pricing and long-dated maturities these markets offer. “Many corporates need a quantum of debt that can no longer be supported by the bank market, or they want the higher flexibility that bond markets give them,” says Citi’s Rainey. “With pricing where it is at the moment – corporates are thinking if there’s ever a time to start financing in bond markets, it’s now. Ryanair’s debut unsecured Eurobond this year is a good example of this. For an airline to get away with doing a senior unsecured issue was pretty phenomenal, and the 1.875% fixed-rate coupon for €850m of BBB+ debt is impressive.”

Chart 2: EU Funding mix 2007 – 2014

Source: Dealogic

Besides this evolution of the bond market, the low-yield environment tends to make bond financing more attractive than bank financing in many cases. “Interest rates in Europe in particular are extraordinarily low and will probably remain low for the foreseeable future, and as a result companies can raise funding very cheaply and for very long tenors,” says BofAML’s King. “Corporates can get 10-20+ year money at very low rates with all-in coupons of 1-4% depending on the credit rating, which is much better than getting shorter-dated money from the bank market, which is generally a five-year market. Bond financing gives you much longer-dated money, allowing you to lock in longer-term rates at very cheap levels, which makes a lot of sense.”

This has also boosted the corporate hybrid debt market, which many companies view in the current low-yield environment as a form of ‘cheap equity’.

An increase in M&A activity is giving the bond market a boost, too. “Acquisition financing is clearly back en vogue,” says Citi’s Rainey. “The increasing confidence in the market is impacting on corporate boards, and we have seen something of an M&A frenzy in sectors such as tobacco, pharmaceuticals and telecoms. This is helped by supportive bank groups – generally corporates are incentivised to replace bank debt reasonably promptly with bond debt – and if they don’t do so then the cost of the bank bridge gets higher and higher in order to facilitate that encouragement.”

“Acquisition financing is capital-friendly for banks given that it’s short term and as such there is demonstrably strong willingness to lend into M&A situations. These take-outs are likely to drive bond volumes over the next year,” he adds.

In the shorter term, low interest rates are also stimulating the commercial paper (CP) market, which, though flagging previously, reached an 11-month high in the US in November. “In the current low-yield environment, the Group can issue CPs at very low rates,” says Brice Zimmerman, Head Treasury Control and Reporting at Novartis. “Also, reflecting the high liquidity in this market, CPs are an attractive source of short-term liquidity that offers a high degree of flexibility as it can be repaid quickly.”

Keeping a balance

Despite the increasing popularity of debt capital market financing (at least in Europe), bank loans remain a core part of most corporates’ funding mix, and the competition between banks (and others) to lend to corporates is intense. “It’s clear that there are a number of banks from across Western Europe, Asia and the US that have been keen to grow their loan books, and as a consequence, the broader loan market has become increasingly competitive. This is seen not only in price or terms, but also in the amounts each bank is prepared to hold in an individual transaction, concludes Barclays’s Nolson.”

Funding choices are often a case of ‘horses for courses’. “Bank financing is still there and is still pretty attractive for the right clients, depending on who they are and what they’re doing,” says Citi’s Rainey. “Companies go to the bond markets for a variety of reasons, but there has not been a huge shift away from bank financing to bond financing. Each has its role to play and both are constructive.”