Centralisation, automation and cost reduction remain the major trends when it comes to structuring the treasury function. With many companies intensifying efforts towards all of the above, it is pertinent to reacquaint ourselves with the basics of treasury models, asking the question ‘does full centralisation really suit every business’?

It is no secret that since the financial crisis, treasurers increasingly want to know where the company’s cash is and how quickly they can access it. Treasury Today’s Asia Pacific Corporate Treasury Benchmarking Study 2014 found that cash management and cash pooling structures are within the top three priorities for corporate treasurers. Moreover, addressing cash flow forecasting and improving visibility over the company’s cash comprised two of the top technology issues – the study concluded that on these points, there is still room to improve.

But what impact do these concerns have on treasury models? Certainly, emphasis on visibility and control is considered one of the drivers behind intensifying interest in centralisation. Moreover, technological advances have made it easier and cheaper to centralise. Technology is no longer the preserve of large corporates.

Operating a centralised structure is not always straightforward however and, as every business has individual requirements, it is important to determine (and periodically re-evaluate) the degree to which centralisation is beneficial and practical from a specific company’s perspective.

Levels of centralisation

Broadly speaking, there are three levels of treasury structure: decentralised, partially centralised and fully centralised. Although full centralisation may be the ultimate goal for most multinational corporations, many companies end up with a partial or decentralised structure simply because it is too impractical for them to operate in any other way. It is to these two that we first turn:

- Decentralised. Treasury policy-making, decisions and activities are conducted by individual subsidiaries. Typically, only a small team is retained at group level to provide advice and support. Subsidiaries may have their own local banking arrangements, will organise their own funding and handle cash management (including short-term borrowing and investments) locally. Payments to and from the parent company will still occur.Decentralised structures work well when the subsidiaries are independent and autonomous units with limited complimentary needs. Local treasury units’ enhanced local operational knowledge and risk awareness is advantageous – especially when the business needs to adapt to unexpected events. However, they face issues with limited automation (no central processes), and potentially lack the leverage or ability to offset surplus cash positions against borrowings elsewhere, among other potential problems of multiplying, rather than minimising, efforts.

- Partially centralised. Arguably a ‘best of both worlds’ approach, a partially centralised model usually involves individual subsidiaries following the treasury policy as outlined by group treasury – often they will also receive advice or instruction. Individual subsidiaries, however, will be responsible for executing deals themselves via their local banking partners. Back office operations may be undertaken at a local level or they may be centralised. Partial centralisation delivers more control while enabling subsidiaries to maintain a degree of autonomy within the front office function. It can also help to increase uniformity in treasury policies and procedures across the group and allows key decisions to be made at a global level with a comprehensive view of cash flow – whilst also retaining local expertise.A common approach to partial centralisation is the regional model. With treasurers rethinking their approach to banking and funding since the financial crisis, the one-bank approach is no longer seen as a viable option. So, with treasurers giving more consideration to regional banking relationships, a regional treasury model is also being mooted as an equally prudent option.

- Fully centralised. With a fully centralised structure, a global treasury centre or regional centres (on behalf of subsidiaries across a specific region or across the group) will undertake policy-making decisions and most, if not all, banking and financial activities. These centres may offer 24-hour services to ensure round-the-clock coverage for all subsidiaries. The organisation of centralised treasury is increasingly built around two objectives – debt capital and risk management – with the aim to source and secure a strong cash flow by placing key decisions at the centre.Centralisation ensures group treasury has standardised operations, greater control across the company with streamlined bank accounts and improved transparency of cash flow. The natural hedge created by matching of financial positions can also result in better margins. Moreover, the concentration of knowledge and experience typically leads to improved results with fewer people and a reduced risk of error.Costs are also likely to reduce – if basic processes of payments and collections are centralised, the cost of those processes decreases: it is a simple economy of scale. Centralisation can, however, lead to a lack of local banking expertise and a loss of responsibility may lead to either (or both) a lack of interest and resistance at the local level.

Centralisation developments

Technological advances have been making it easier to centralise treasury operations, lifting both practical and financial barriers. Technology has come to be seen as a key enabler in the implementation of treasury centres and integrating company platforms with those provided by the company’s banking partners, therefore, a key success factor. Furthermore, some regulatory initiatives favour the adoption of centralised treasury structures. The persistence of general economic and geopolitical uncertainty means more corporates with global operations are looking at streamlining their treasury management into full centralisation.

The advent of cloud computing is also opening up new possibilities for treasury centre locations. Access to data sources and solutions in the cloud means that it increasingly doesn’t matter where the treasury centre is situated. This development means that labour costs have emerged as one of the primary factors in determining location.

Of course, labour costs shouldn’t be treated as the sole arbiter of location. Technology and communications infrastructure, time zone considerations, political stability and the local regulatory environment, should all be considered as part of the selection process.

Issues for consideration

However, it certainly isn’t a case of one size fits all. Some responsibilities of the treasury department can benefit more obviously from centralisation – increased visibility of information, for example. Centralised information enables a business to ‘think globally and act locally’ ensuring sound management and the ability to prevent problems from a comprehensive group view – without having to compromise people on the ground managing both local risks and local opportunities.

Whilst other areas of focus consistently offer savings when centralised (for example payment processes), in some instances companies must question whether the process involved would be handled better locally. Certain commodities hedging or transactions requiring reporting to central banks provide two examples.

When deciding on a treasury model to operate, the following points outline some issues to consider:

- Cost and cost saving. The financial implications of initial expenditure and ongoing costs must be weighed against the benefits and potential savings for each model.

- Group-wide support. The chosen model must gain full support at management and board level; the understanding from employees at both group and subsidiary levels is also required.

- Legal, regulatory and tax implications. The significance of changing structures and establishing centres in different regional locations (with potentially different tax, regulatory and legal requirements) should be investigated.

- External relationships. Relationships with any banks and vendors impacted by any changes should be managed well – this involves negotiating advantageous terms and handling the declaration of any loss of business appropriately.

- Technology. What steps are required to progress to the desired system infrastructure? Of consideration here is whether legacy systems are able to migrate or integrate – this could have an impact on costs.

- Operational aspects. Any transition procedures, project management and staffing issues should be addressed with minimal adverse impact on daily treasury activities.

The treasury centre

Where a centralised structure is chosen, a treasury centre will be encountered. These are centralised treasury management functions, legally structured as a separate group entity or branch. Treasury centres are normally located in a tax-efficient environment, reducing the bill on transactions and profits associated with the entity. Also of importance is the location’s possession of highly developed banking infrastructure and a wealth of financial services expertise. Moreover, technology and communications infrastructure, time zones, political stability and local regulatory environments should all be considered when choosing where to locate a treasury centre.

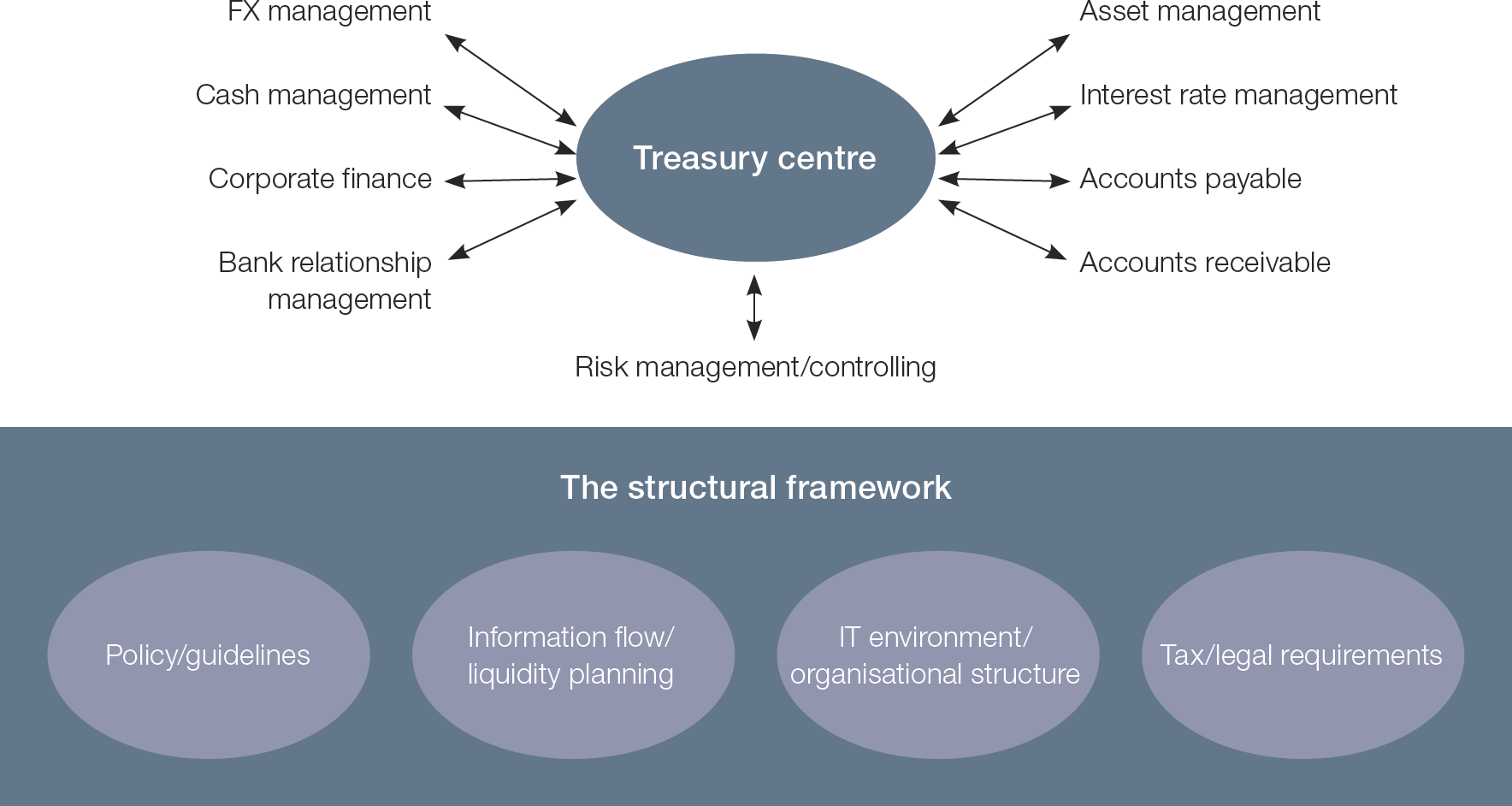

A treasury centre will provide financial management and transactions services for the other group entities including, but not limited to:

- Internal and external payment services.

- Cash pooling.

- Asset management services.

- Financial markets research.

- Monitoring and financing capital requirements of group companies.

- Risk management analysis and monitoring.

It is important to be aware that the capabilities and activities of a treasury centre are defined by each individual case. In some instances, responsibilities may be best managed locally as not all countries where group companies are located will necessarily permit the concentration of all treasury centre activities.

Nevertheless, operating with a centralised treasury can lead to numerous improvements, including: governance improvements (co-ordinated and central database, group-wide reporting, standardised procedures), cost reductions (higher volumes and fewer transactions, reduced financing requirements) and efficient tax management (optimising global tax position).

Finding the right spot: treasury centres in Asia

As more and more corporates centralise their operations and look to establish a treasury centre in Asia, the big question is which location is best? For many corporates the choice is between the region’s two key finance centres: Singapore and Hong Kong.

Singapore is currently the dominant treasury centre location in the region. The country offers a business-friendly environment, deep and well-educated talent pool, and best-in-class infrastructure which has seen it become the regional hub for many multinationals. In addition to this Singapore has a liberal regulatory environment, an excellent sovereign credit rating, a deep and liquid FX market and a legal system based on English common law. The city’s status as a financial centre also allows treasurers access to best-in-class banking services.

On top of this, Singapore offers corporates a strong incentive package to locate their treasury centres in the city in the shape of its Finance and Treasury Centre (FTC) award. Qualifying corporates receive a concessionary tax rate of 10% on all fee income received from treasury activities and an exemption from withholding tax on interest payments.

Hong Kong, the regions second key treasury centre location, is popular with companies that have a significant presence in China. On the whole it offers a similar proposition to Singapore with a business-friendly environment, legal system based on English common law, liberal and well-developed regulatory framework, deep, well-educated, international talent pool and excellent infrastructure. Corporates in Hong Kong also have access to a wide range of banking services and a well-developed RMB market.

One area where Hong Kong has lagged behind Singapore is in its tax incentive programme. But recent developments have looked to change this and address the tax imbalance which put some corporates off operating in the territory. The Hong Kong Monetary Authority have proposed that tax payments on intercompany loans will no longer be larger than profit earned – thus bringing the territory’s incentive package in line with Singapore.

Although Singapore and Hong Kong are currently dominant, there are other locations in the region such as Shanghai, Malaysia and Thailand which are all also looking to get a slice of the treasury centre pie. Currently, Shanghai is offering the strongest proposition and its attractiveness is growing as China further liberalises and the country becomes more critical to businesses. But, it remains to be seen if these locations will attract enough corporates to challenge Hong Kong and especially Singapore as the region’s dominant locations.

Diagram 1: Typical centralised treasury structure

Source: Treasury Today’s European Cash Management Best Practice Handbook 2014

The organisational structure of a treasury centre

Depending on the group’s management philosophy, the treasury centre has a choice of two models to adopt:

- The treasury centre acts as central agent, operating all financial transactions for the group companies in their name, compensated on a cost plus basis.

- The treasury centre acts as the group’s central in-house clearing bank, either on a shared service centre basis (which means that the group entities have direct relations with the treasury centre) or in competition with third-party banks.

Both models centralise the treasury know-how of the group. In addition, the in-house bank (IHB) operates the group’s financial management as its own business. Cost savings, as well as additional income earned, arise at treasury centre level.

If a treasury centre is organised according to an IHB model and is competing with other third-party banks, it will usually operate as a profit centre. The group companies’ financial needs are met on a price level applicable to a third party.

The question of whether a treasury centre operates as a cost, service or profit centre has a direct impact on where the treasury centre is located. Indeed, a treasury centre acting as a profit centre has a clear advantage if operating in a low tax jurisdiction.

In-house banking structures

IHB structures are typically established by medium-sized businesses upwards. An IHB acts as the main provider of bank services to all group subsidiaries. This may be established on a global scale or on a regional basis. Instead of using local external bank partners, each subsidiary channels its cash flows through bank accounts held at the IHB. The bank then nets out the resultant debit and credit balances across the group. The IHB may also use a netting process for foreign exchange (FX), as well as for the payable and receivable amounts owed between the subsidiaries.

It can be noted too that the IHB may organise inter-subsidiary lending. When all the internal transactions have taken place, any remaining investment, financing and hedging needs are fulfilled by external banks chosen by the IHB from its preferred group of relationships. Some multinationals have restructured their inter-company loans to repatriate cash and achieve tax efficiency. In the US, for example, there are strict ‘arms-length’ rules on interest charges which, according to Ernst & Young (E&Y), “should reflect the interest rates on loans between unrelated parties with similar terms, including duration and credit standing of the borrower.”

However, as an example of what can be achieved through such a structure and practice, Toyota Financial Services (TFS), the finance and insurance brand for Toyota in the US, built an inter-company lending facility for global affiliates and achieved a $25m saving through reduced interest expense alone.

Centralised treasuries may operate an IHB within their overall model. However, an IHB can also be used to enhance operations whilst keeping a decentralised structure.