The syndicated loan has proved a useful product in supporting China’s recent growth. But will the strong demand for loans seen in recent years continue? And if it does, will the banks be in a strong enough position to meet it? We take a look at some of the key challenges now facing the markets fuelling China’s growth engine.

In much of Asia, the global financial crisis brought about a sharp decline in syndicated lending. But that didn’t happen in China. On the contrary, China was one of the few countries where syndicated lending continued to grow through the crisis. Syndicated lending volumes have continued to grow steadily over recent years as well, to the point where the product is now one of the most popular sources of finance for businesses in China.

The credit financed through the syndicated lending channel has therefore played a critical role in fuelling the nation’s recent growth story. But will it continue to in the years ahead?

The outlook is mixed. Despite the talk of a ‘hard landing’, China’s official growth rate in 2015 was 6.9%. Slowing – but still robust – growth figures, should mean that demand is still there (especially while M&A continues to surge and more corporates look to refinance the foreign currency loans weighing on the balance sheet). The real question, then, is around supply and, in particular, if the ability of banks to lend might be restricted by the non-performing loans (NPLs) now accumulating on their balance sheets.

But there is also another, perhaps bigger, story to tell here. The history of China’s loan market very much mirrors the country’s economic development, more specifically the transition from a centrally planned economy to a market-based one. Consequently, syndicated lending in particular has been subject to tremendous changes in recent years and with the economy continuing to open itself up to market forces, there is very likely more still to come.

The journey so far

In the not too distant past, syndicated lending in China was the near exclusive domain of Chinese banks, the so-called ‘Big Five’ in particular. In 2006, this began to change following reforms that allowed more foreign participants to commence lending in renminbi onshore and in foreign currency offshore, often collaborating with domestic banks to take advantage of their superior origination and distribution networks. Much of the liquidity supplied through the expanding loan market went into infrastructure financing, where syndicated loans became the preferred vehicle for extending the credit since it reduced the risk of default caused by a single bad project. Since large amounts could be arranged relatively quickly compared with the other available channels, they also became popular with borrowers. Before too long syndicated lending began to dwarf other financing channels in China.

Today China dominates the syndicated lending market in Asia, with volumes of $100bn recorded in H215, accounting for around 31% of all lending in Asia, excluding Japan. Chinese banks remain the dominant players in the domestic market and, furthermore, have been very active players across the Asia Pacific (APAC) region with Chinese institutions representing four of the top mandate arrangers in the region. Even in highly developed markets like Australia, Chinese banks have been competing with domestic institutions and participating in syndicated deals. Foreign banks, meanwhile, tend to focus their financing activities offshore in Hong Kong in credit denominated in euro, dollar or yen. Occasionally foreign banks will arrange a syndicated loan for a European subsidiary that have not been able to build relationships strong enough yet with the Chinese banks. By and large, however, most of the large RMB denominated transactions we see being executed onshore in China come from Chinese lenders.

A turning point?

Taken together though, the credit extended through syndicates onshore and offshore account for much of the credit growth that we have seen across the region in recent years. “China has really been at the forefront of syndicated lending in APAC in the past few years, largely due to the overall growth in investment in infrastructure,” says Amit Chopra, Syndicated and Commercial Lending Specialist, at Misys. “If we look at year-on-year growth, 2015 has not been as great in terms of percentage growth, but China has still been the biggest contributor in the region, excluding Japan.”

More moderate syndicated lending activity is being reported offshore especially. Does this mark the beginning of a turning point in which demand for syndicated financing begins to fall off, both in Hong Kong and mainland China? Not necessarily. To understand why syndicated lending has not been so robust during the past year, it is important to consider where a large chunk of the demand the banks were seeing originated from. While a lot of demand for financing has come from clients with an underlying requirement for foreign currency, such as an acquisition, a sizeable portion of it has also been arbitrage driven. For some companies it made sense to borrow in foreign currencies like US dollar or euro, before converting back to renminbi to arbitrage between the low offshore borrowing costs and the high onshore CNY deposit rates. But since the two downward ‘adjustments’ to the currency made by the Peoples Bank of China (PBoC) last year, activity around that carry trade has all but vanished.

“I think demand is still there,” a loan syndications head at a foreign bank in China told Treasury Today Asia. “It is a little bit more subdued than it was, but the nature of the demand has changed a little bit,” he explains. “A lot of [arbitrage driven financing] has fallen away over the past six months. But there is still a drive to go offshore and buy and acquire Western companies, whether it be to obtain technology, manufacturing capabilities or natural resources offshore. That strategically driven demand for credit remains in place, the bit that has fallen away is the companies borrowing cheaply in USD.”

China has really been at the forefront of syndicated lending in APAC in the past few years, largely due to the overall growth in investment on infrastructure.

Amit Chopra, Syndicated and Commercial Lending Specialist, Misys

Phil Lipton, Chairman, Asia Pacific Loan Market Association, agrees that diminished opportunities for arbitrage is likely to mean less offshore syndicated lending in foreign currencies. “I think we have seen a shift back to onshore borrowing,” he says. “That is not just the depreciation – China has cut interest rates too, so raising money in China is now a lot more attractive than it used to be. For these two reasons there is more liquidity in the country now. As a result, you will see companies, in relative terms, raising more onshore – and I think that is going to increase going forward.”

Bad loans

Meanwhile, the outlook for the onshore loan market remains relatively favourable into the medium term, underpinned by prospects for strong – although decelerating – economic growth (which the IMF expects to remain above 6% until 2020). However, slowing growth and the commodities slump will have some impact on the market, with lenders expected to become a little more selective in what they finance. Already we are seeing a decline in syndicated loans and one sector, in particular, is facing some steep credit challenges.

In a 2015 report, analysts at Australian investment bank Macquarie looked at the figures on China’s debt profile and found that companies in sectors such as mining, smelting, and material now have debt levels that are so high the firms are under “extreme strains to survive”. Essentially, corporate debt in this sector increased substantially in the past three years, and the earnings of the companies who have borrowed have not increased at anywhere near the same pace. Naturally, banks are becoming a little reticent when it comes to meeting demands emanating from this space.

But while that has been the focus of much of the concern, the change in sentiment has not been entirely restricted to the commodities sector. On the contrary, privately owned enterprises and even some of the less eminent state owned enterprises (SOEs) are also feeling the squeeze. Several years ago, banks were lending to nearly everyone who required it. But today, financing – especially for companies linked to commodities – is becoming much more difficult. There is also less enthusiasm to finance third or fourth tier SOEs than before, while some banks refuse to touch privately owned enterprises altogether, due to the perceived risk.

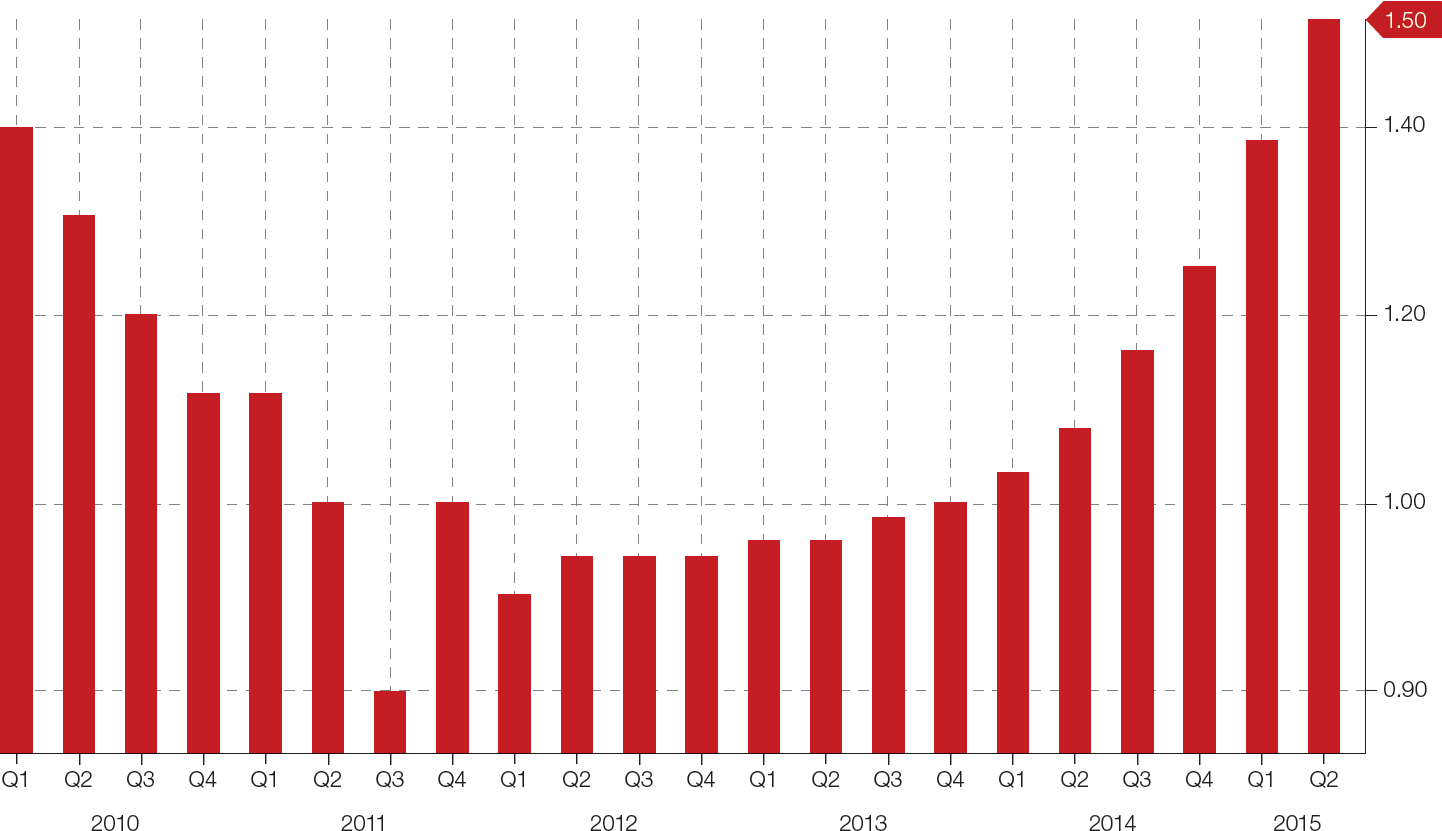

Also weighing on the minds of lenders, perhaps, is asset quality deterioration from problematic legacy loans. New non-performing loans (NPLs) held by Chinese banks more than doubled in 2015 according to recent news reports. Even by the Chinese authorities own, more optimistic statistics, bad loans rose to RMB 1.27trn by the end of 2015, sending the NPL ratio up to 1.67%. “The NPL ratio is alarming,” says Chopra. “And it gets even worse when you look at the second and third tier of the banking sector.”

Chart 1: China NPL ratio

Source: Bloomberg

This worrying development has not escaped the attention of the institution responsible for regulating the Chinese banking system, the China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC), who recently introduced a minimum loan loss provision ratio (although the central bank, now in full easing mode, recently cut the requirements in order to stimulate borrowing and prevent a further currency devaluation). Consequently, banks now have to set aside more cash than they did previously for future losses by the total of NPLs.

Chopra says this change will inevitably have a big impact on the flow of credit and syndicated lending in particular: “The CBRC is taking an active step in this and, obviously, this will impact the banks’ ability to lend as openly as they did in the past,” he notes. “One of the steps is around Loan Loss Provision (LLP) ratio and Chinese banks are required to keep a minimum ratio of 150% and some of the large banks are currently very close to this LLP ratio. This obviously means that banks will have to infuse more capital if they want to remain above this ratio while continuing to lend in market. The NPL’s and interest rate liberalisation can have an impact on bank’s profitability going forward.”

But credit should continue to flow, so the experts say, to the less distressed areas of the Chinese economy, irrespective of the NPLs accumulating on the balance sheets of banks and the debt troubles of commodities firms. Perhaps this is why, despite all the market turmoil at the beginning of the year, credit expanded by 12.7% in January, the fastest pace since April 2015. “The banks will be lending to companies where they are seeing growth,” says Lipton. “There may be an aversion to where there is stress in a sector. Corporates that are having more problems are going to be a lot more cautious about borrowing new funds and leveraging up, whereas on the domestic front there’s still growth, so we will probably see banks moving their focus in that direction.”

Advice for borrowers

What should treasurers take from this? Well, those who require financing in the near future – as many companies will all the while the M&A upsurge continues – should not have too much difficulty raising it through the loan market, with the notable exception, that is, of all those heavily leveraged companies in sectors most exposed to the slump in commodity prices.

For everyone else, the advice is twofold: do not hang around, and do not get too distracted by the pricing. Companies with a financing requirement should go to the market as early as possible, and understand that it may make sense to pay for certainty in the current market. That might mean paying banks to underwrite or dealing with banks that are slightly more expensive, but the cost of debt is not going to be as important as making sure the company achieves what it want to achieve from a financing perspective.

But with lower borrowing costs and wider availability of funds on the debt capital markets, will syndicated loans continue to be the fuel in the Chinese growth engine? Chopra believes we will see more companies in China financing themselves through bond issuance going forward, but this should not, he says, have too great an impact on the demand for syndicated loans. “The bond market is certainly an attractive option, especially for organisations that have already exhausted syndicated lending or wish to diversify their overall portfolio”, he adds. “But I would say that any company that wants to raise considerable capital from the market, syndicated lending will continue to be one of the favoured vehicles.”