The Covid pandemic and an increased focus on corporate social responsibility have posed risk management challenges for treasurers. While the risks may remain the same, the focus is shifting and treasurers are alert to how rapidly the landscape can change.

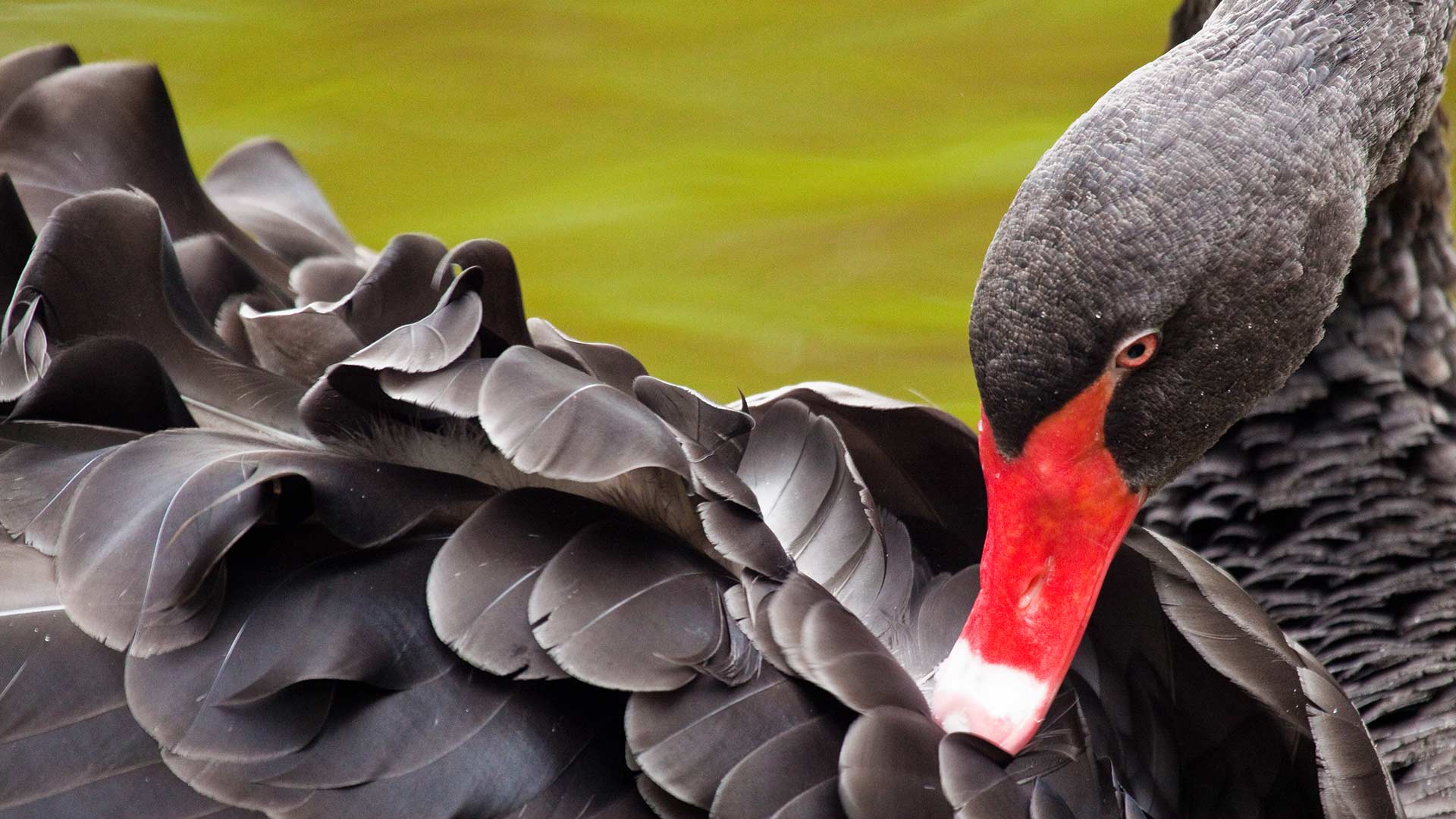

As a ‘black swan’ event (although the jury is out on whether it can be defined as such) the COVID-19 pandemic posed significant risk management challenges for treasurers. Add to that an increased focus on climate change, the impact of Brexit on UK treasurers and even the Suez Canal obstruction in March, and treasurers and CFOs face a new risk landscape.

In the initial phases of the pandemic, treasury teams had to rapidly assess their firms’ overall liquidity positions and ensure they could access liquidity when they needed it. Keeping a company going, both operationally and financially, was a key concern. In addition, treasury teams had to transition to remote working environments.

This took place against a background of volatile financial markets and uncertainty about current and future revenues and cash flow. Many businesses focused on preserving cash, including retrenching staff or signing up to the various furlough schemes offered by governments and temporarily shutting down operations. They did this while seeking out potential lines of credit and other ways to maintain liquidity.

According to professional services firm Marsh McLennan, the adverse effects and uncertainty for businesses that arose from the pandemic will likely persist for some time, “with the worst possibly still to come”. This underscores how important cash preservation is for businesses, it says. “In addition to any actions they may have taken so far, businesses will likely need to explore other solutions, such as claims and collateral cost reduction strategies, credit insurance products, premium financing, and the use of captive insurers – all of which can help them stay liquid,” the firm says in an April 2020 briefing on liquidity.

Sarah Boyce, Associate Director – Policy and Technical at the Association of Corporate Treasurers, says liquidity risk and business continuity were “front and centre” for all treasurers at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Boyce says while new risks are not emerging, the focus given to certain risks has changed. “Treasurers are expanding their remit and rather than focusing on the biggest risks, they are looking at all risks, given the number of black swan events that have emerged,” she says. “Treasurers and CFOs realise it could be the least obvious corners of the organisation that could throw out the next challenge.”

This is a point also made by Damian Glendinning, Singapore-based Chairman of the Advisory Board at CompleXCountries, a global peer group network for senior corporate treasury professionals. “It is difficult to say what impact Covid has had on risk per se: what it has clearly done is to show that risks can emerge in ways none of us could easily envisage.”

Leonardo Orlando, an executive in Accenture’s Finance and Risk Practice, says the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on treasurers very much depends on the type of industry, the markets in which a company operates and its financial situation. “However, common to all treasurers was the fact that Covid was a unique, global event that affected all companies in all countries,” he says.

The initial reaction was generally one of minimisation – treasurers tried to reduce their risk exposure in order to prevent the situation worsening. After that, he says, corporate treasurers looked to put in place new scenario modelling to ensure they understood the problem and could capture similar events in different ways and understand the business impact.

Royston Da Costa, Assistant Group Treasurer at plumbing and heating products distributor Ferguson plc, has a similar view. He says while risk always has been a key treasury responsibility the assumptions had been based on “known risks”. The pandemic, he says, is “the first time the whole planet was affected by a crisis that did not just impact a few economies but also promoted the position of treasury technology to the forefront of a treasurer’s priorities”. Cash flow forecasting solutions have gained a boost from the pandemic as corporates recognise the importance of liquidity and forecasting of their cash positions.

Like Glendinning and Boyce, Da Costa says the emphasis on risk is changing, with the risk of cyber fraud gaining more importance as employees work from home and phishing and other attacks increase. The pandemic has caused banks to focus on shrinking the margins between assets and liabilities, with a stronger focus on off-balance sheet funding solutions, says Andreas Bohn, Partner at McKinsey & Co in Frankfurt. “Corporate infrastructure and project financing is moving away from bank balance sheets and towards private equity funds and direct lending platforms. The impact for a treasurer is that they have more options and need to adapt.”

Another issue bubbling away for many corporate treasurers is climate change, and the wider environmental, social and governance (ESG) agenda, once referred to as corporate social responsibility. Under the Paris Agreement, a legally binding international treaty on climate change which came into force in November 2016, countries have committed to limit greenhouse gas emissions as soon as possible to achieve a climate neutral world by 2050.

According to the United Nations, zero-carbon solutions are becoming competitive across economic sectors representing 25% of greenhouse gas emissions. The trend is most noticeable in the power and transport sectors and has created many new business opportunities for early movers. By 2030, zero-carbon solutions could be competitive in sectors representing over 70% of global emissions, says the UN.

“Whilst the Covid pandemic has had a profound impact on credit and liquidity risk, the bigger challenge will be incorporating decarbonisation into credit models and looking at the systematic risk this poses for some industries,” says Philip Freeborn, Group CIO, COO and Head of Pricing & Risk at consultancy firm Delta Capita. “ESG reporting is not transparent enough and relies too much on self-reporting rather than on objective third-party assessment of companies and their supply chains.”

This is also an issue highlighted by Boyce. “Integrating ESG into treasury operations is an added complexity, mainly because there is a lack of consistent methodology about how activities will be treated by investors and ratings agencies,” she says. Consistent metrics and data are difficult to find and there is nervousness around claims of ‘greenwashing’ – misleading information about how environmentally sound a company’s products are. “For treasurers, the challenge is to pick the right banking partners. As greater clarity emerges around methodologies and disclosure requirements, there will be more activity in the green finance space,” she says.

A challenge for treasurers in ESG is the assumption that an organisation can instantly become green, adds Boyce. “That can’t happen and has to be an evolution. There are fears that some organisations in ‘brown’ industries may become unbanked or unattractive to banks. Transition to net zero carbon emissions is a big challenge for treasurers in those organisations.”

Moody’s Investor Services has reported soaring levels of green, social and sustainability bond issues. In Q121, sustainable bond volumes more than tripled year-on-year to reach a record total of US$231bn, a 19% increase over the previous quarter. Moody’s attributes the growth to a heightened level of government policy focus on climate change and sustainable development and strong, sustained interest among debt issuers and investors.

Glendinning notes that ESG issues have been growing in importance for companies, and therefore treasurers, for some time. “From a risk point of view, everyone is aware of the potentially significant impact on a company’s reputation of a highly publicised incident involving pollution, labour force abuses or corruption scandals,” he says. “However, treasurers in some industries, such as oil or tobacco, are finding some banks will refuse to work with them, and ESG-conscious investors are placing increasing demands as a condition for equity and bond funding.”

Many treasurers are complaining that this activism, while not a problem in itself, is causing issues due to the lack of generally accepted, clear, and consistent ESG measurement processes, adds Glendinning. “The concern is that one rating methodology may give a good score, while another gives a bad one.”

Da Costa does not believe treasurers have “fully embraced” ESG. While banks and fund managers appear to be advanced in providing an array of ESG products that corporates could use, he says he is uncertain as to whether corporates have kept pace with these developments.

Adrian Sargeant, CEO of advisory company ESG Treasury, says ESG will release more black swans into the market for which treasurers must be ready. “There is likely to be some fundamental change and whether you are a corporate or an individual that borrows money, you have to ask whether you are involved in a sector that has long-term prospects. Will a bank lend to a company in the oil sector, for example, to fund the cost of their transition to net zero?” he asks. Whole sectors, such as the energy sector, will have to transition to renewables.

Treasurers in some industries will face new challenges in regulatory risk as the response by governments to the pandemic demonstrated how quickly regulations can change. This is likely to happen with regard to climate change obligations as we move closer to the net zero emissions deadline of 2050, says Sargeant. “There could be a cliff edge moment where people who have been working on responses to climate change for decades have been doing too little, too late – the effort to fix things will be too great. This will affect a treasury’s ability to raise funding, with some loans coming off bank balance sheets in the future.”

One of the biggest changes in the risk landscape, says Boyce, is the increased engagement with business risks. “Supply chain risks are becoming a big thing. They make cash management more complex and the cash cycle may be longer as a consequence of the changes we are seeing due to the pandemic, Brexit and even the Suez tanker episode,” she says.

The Suez event, when the tanker Ever Given was grounded, was a good example of the fact that even during ‘normal’ times a relatively local event like a tanker being stuck in the Suez Canal can have global repercussions because of the nature of the globalised supply chain, says Boyce.

Technology is likely to play a greater role in risk management going forward. “Not surprisingly, more treasurers are investing in technology,” says Da Costa. Thorough reviews of processes and treasury infrastructures are also being undertaken.

Boyce says there is greater use of artificial intelligence and data analytics in treasury operations, but there is nothing particularly different about the risk framework, “it is still a matter of identifying, assessing, managing and reporting on risk. What has changed is how treasuries undertake these activities.”

Digitisation of the treasury was a disruptor before the pandemic, but has been accelerated since, says Accenture’s Orlando. “Some corporates have fast-tracked the onboarding of new technologies, analytics and techniques for risk management. These will enable the treasurer to better monitor liquidity on an end of day basis, and potentially in real time across the world.”

Glendinning is sceptical about treasury technology, observing that new products are constantly emerging, “but they are often old approaches wrapped up in new instruments. There is undoubted promise in technologies, such as artificial intelligence and data mining, to help identify new and emerging risks – but we are not yet seeing much practical adoption.”

Given the scale of the pandemic crisis, the fact that businesses continued to operate has reflected well on treasurers and their risk techniques, demonstrating they are good at what they do, says Boyce. “Treasuries are well-positioned to respond relatively smoothly to these events – they know what they have to do and get on with it.”