We have studied the economic forecasts of the major banks and multinational institutions such as the IMF and OECD. Generally, the analyses come down to the following.

The US quietly moves ahead

The US economy will continue to grow by roughly 2%. That is, growth has been below this level in recent quarters, but it is expected to receive a slight boost from the monetary stimulus measures in 2019 – not just in the US but worldwide – stockpiling and not too many setbacks in (global) trade.

After 11 years of growth, there is not much reason to anticipate considerably more. However, a recession is also unlikely. Most recessions occur because central banks apply forceful monetary deceleration, but this prospect is non-existent at this point. Indeed, inflation will remain very low because the forecast is persistent low growth.

However, there is a political risk. Elizabeth Warren could become the next US president. Many of her policies are harmful to (present-day) business. However, the markets are not overly concerned about this. Indeed, the US will not choose a(n) (ultra) left-wing president any time soon. Should this happen, many of Warren’s plans will be watered down considerably by Congress.

Most analysts anticipate that, in view of the above, US economic growth will be at around 2% for the time being, inflation and interest rates will stay at low levels, and the Fed will continue to pursue a loose monetary policy. This is favourable for share prices and negative for the dollar.

Europe is vulnerable

Growth forecasts for Europe do not far exceed 1%. Although the trade war will not escalate, it will continue to have a negative impact on global trade. The European economy is very sensitive to this. Furthermore, Brexit stays a fairly uncertain factor. Prolonged uncertainty surrounding Brexit is negative for economic growth of Europe as a whole. However, the biggest problem lies with the banks. European banks generally have a shortage of equity capital and do not earn much from credit supply with the current interest rates. This restricts credit supply considerably, especially because roughly 80% of credit supply in Europe is operated by the banks (while roughly 80% of US credit supply is operated by the capital market).

The current excessively low inflation rate will decline rather than rise, due to the combination of 1% growth (just below potential) and the still available reserve capacity. This is why the European Central Bank (ECB) is pulling out all the stops, purchasing €20bn a month in bonds and creating surplus money. Using forward guidance, the central bank also indicates that it will not raise its short-term interest rates for the time being. The problem is that the ECB has been pursuing a very loose monetary policy for some time, but so far this has not pushed up growth and inflation to any significant extent.

This renders the situation in Europe fairly vulnerable, as the slightest shock could trigger a recession and deflation. This could rapidly turn into a self-sustaining negative deflationary spiral in view of the high debt levels.

Finally, it also plays a role in the background that the European population is going to age fairly quickly – more so than in the US – which means that more and more non-working people will have to be sustained by working people. This is certainly not conducive to growth.

Japan and China are also unlikely to take the lead

The situation in Japan can be compared to that in Europe, but it is more acute. Growth and inflation expectations are slightly lower than those for Europe. The same applies to inflation. Japan is therefore very vulnerable to a negative shock. This is a particular cause for concern, as Japan is basically powerless in terms of fiscal and monetary stimulus. Public deficits and debts have soared to exceedingly high levels, while the central bank has lowered its rates to the greatest possible extent – even lower interest rates will limit credit supply – and is purchasing bonds and shares on a large scale. It is therefore a miracle that this combination has not yet led to far higher inflation and/or a currency crisis. However, a further deterioration in public finances and/or an even looser monetary policy could bring this about.

Everything is tightly controlled from above in China. The expectation is that Beijing wants to and is able to prevent a considerable slowdown in growth. Nevertheless, the Chinese economy is suffering a great deal from the trade war. In addition, China is unable to apply fiscal and monetary stimulus on a large scale without raising debt to excessively high levels. This is why Chinese economic growth is generally expected to be slightly below 6% next year.

A recession is unlikely, but the scenario is not exactly favourable

This situation has two important consequences for the rest of the world.

- Increasing overcapacity is evident worldwide in more and more parts of the economy – due to low growth in the industrialised countries, stagnating global trade as a result of the trade war and the slowdown in Chinese growth. This, in turn, exerts downward pressure on wage increases and inflation almost everywhere.

- Low growth and the trade war are depressing the rate of the Chinese yuan. This also reduces the exchange rates of the relevant currencies in most Asian and other emerging markets. This is basically favourable for their competitiveness, but it does not lead to far more exports as growth is very low everywhere. However, it causes the high dollar debts – which exist in most emerging markets – to increasingly bear down on the relevant economies. This therefore prevents the relevant markets from providing their economies with more monetary stimulus. Many emerging markets therefore hope that the Fed’s loose monetary policy will soon lead to a lower dollar exchange rate. However, this is a slow process because a very loose monetary policy is being pursued everywhere, and US interest rates are still positive.

At this point, the general expectation is that the global economy will avoid a recession in 2020, although growth and inflation will stay at low levels. It is therefore also likely that central banks will continue to pursue a very loose monetary policy. The central banks themselves indicate that this might not be enough to prevent the economy from sliding down after all, and they are therefore increasingly calling on the fiscal authorities to come to the rescue. However, policymakers find it very difficult to accommodate this request, as long as the economies continue to grow.

For many years, they have announced that public deficits should be reduced rather than the other way around. This cannot simply be turned upside down now – without a crisis. In view of the above, it is not surprising that interest rates are at very low levels everywhere and will, on balance, likely remain low in 2020 (but we expect a great deal more volatility in the currency markets).

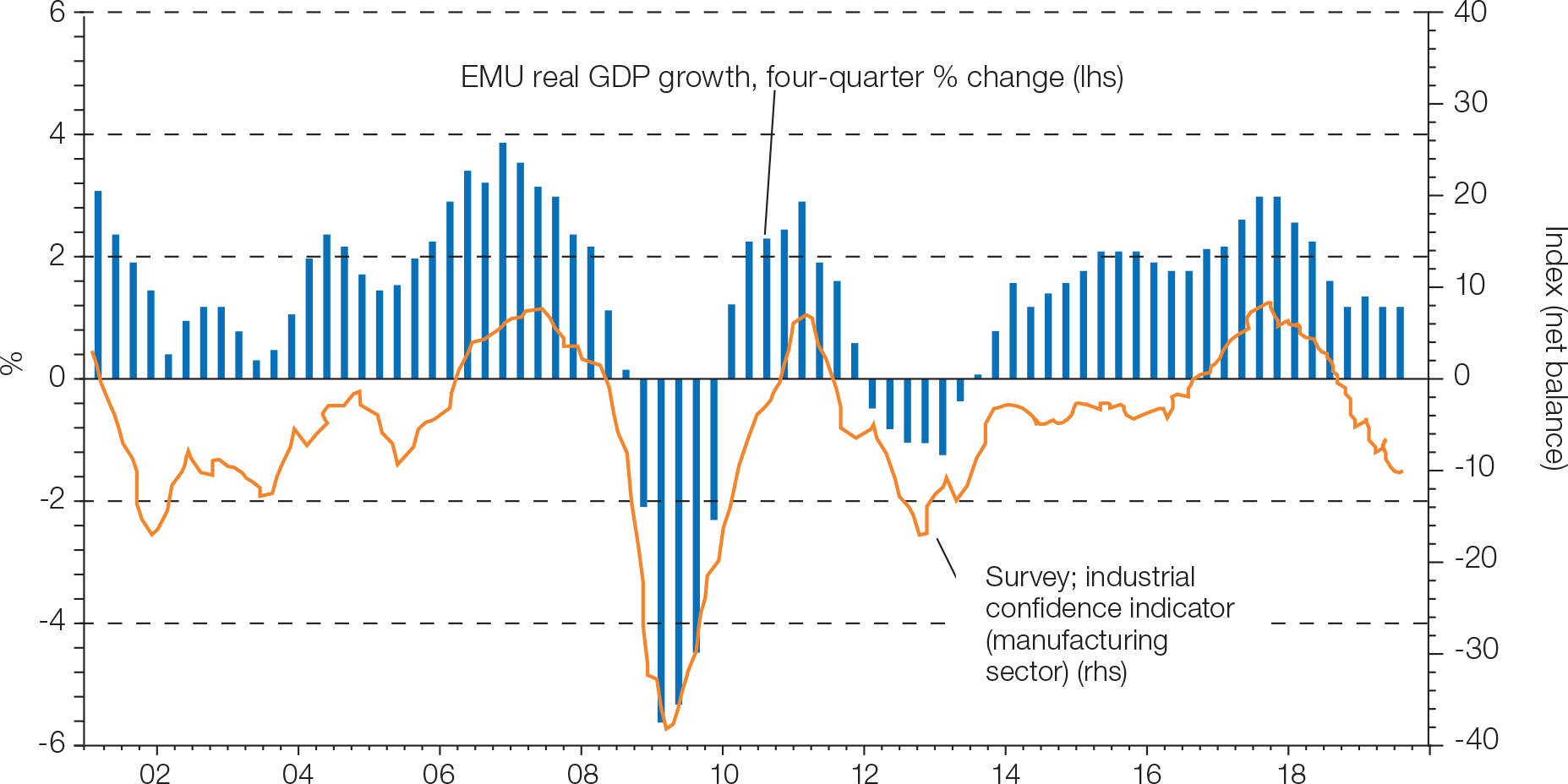

Chart 1: EMU economic data remains rather downbeat

Source: Refinitiv Datastream/ECR Research