With the cash stockpiles of multinationals in Asia continuing to expand and Basel III changing how a bank views its client’s deposits, there is a growing level of interest from corporate investors in what Asia’s nascent money market fund industry has to offer. We take a look at the prospects for funds in some of the region’s key markets in the years ahead.

Never before have Asia’s multinationals had so much cash on the balance sheet – and right at a time when certain deposits are becoming less attractive to banks. But will it be the region’s money market funds (MMFs) that emerge as the big winners if corporates are forced to look for alternatives to holding all their cash with banks?

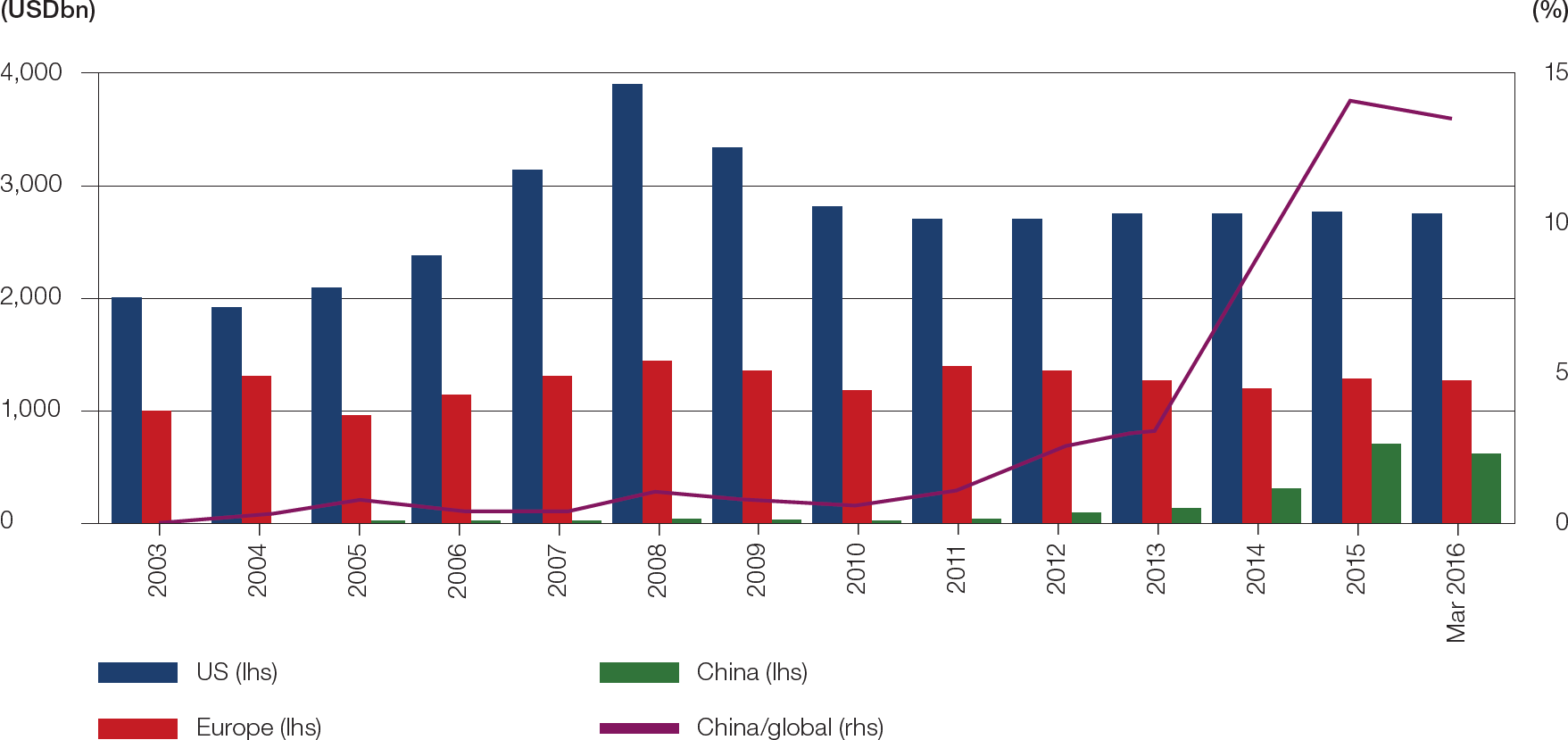

The MMF industry in Asia has already undergone an astonishingly rapid growth over recent years. At the heart of this trend has been China, where the MMF industry is but a decade old. Total assets held by funds in China surged six-fold to RMB 2.2trn between July 2013 and December 2015, according to a recent research note by Fitch Ratings. In 2010, the industry in China accounted for a mere 1% of total MMF assets. Today the figure stands at 10%. The development of Asian capital markets has facilitated this development. A growth in the range and volume of assets available to invest in has allowed for larger and more diversified funds to emerge.

Now asset managers believe MMFs could be on the brink of a second burst of growth. Amid a dearth of capital investment opportunities, the cash stockpile of corporate China now stands at a whopping $1.2trn, having increased by 18% in the last quarter alone. In South Korea, meanwhile, companies have around $270bn idle on the balance sheet, and publicly traded companies in Japan are said to have amassed reserves of some $828bn. That represents a lot of cash that may soon have to find a new home.

Under the Basel III Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) banks must hold reserves of as much as 40% against some corporate deposits deemed likely to flee during times of crisis. In the US and Europe, we are already seeing banks taking steps to discourage such deposits. But the impact of the LCR in APAC has so far been rather muted, relative to other regions. J.P. Morgan Asset Management’s Global Liquidity PeerView study, for instance, found that treasurers in APAC are significantly less likely to have been encouraged to move non-operating deposits off their banks’ balance sheets compared with peers in the Americas or Europe.

But some believe it is only a matter of time before more treasurers in the region start having those conversations with their banking partners. “We expect to see more growth in assets under management (AUM) over the next couple of years,” says Simon Bourke, Director, Institutional Business Liquidity, Hong Kong, HSBC Asset Management. “Some of this growth will be driven by regulatory changes such as Basel III; developments which we expect to support the growth of in funds like our HKD fund targeted at institutional clients.”

Aidan Shevlin, Head of Asia Pacific Liquidity Fund Management, J.P. Morgan Asset Management shares the view that interest in institutional MMF products could grow further as the banks begin to treat deposits differently under the new Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) rules. “This year we have definitely seen a change in tone from the banks,” he says. “It’s been evident that clients are starting to become more aware of the changes, and they are starting to ask us questions about them. It definitely could be a good tail wind to the MMF industry in the years ahead.”

Growing sophistication

Adding to the optimism of asset managers is the growing acceptance of the money fund product beyond its traditional customer-base. Originally, institutional MMFs sprung up in Asia mainly to meet the demand of western international companies that used the products in their home markets and sought something similar as they expanded into Asia. But now companies domiciled in Asia are showing interest too. “What we have seen recently is the growing sophistication of local investors,” says Shevlin. “They are no longer satisfied with time deposits or local standards. So there is definitely growing demand in that area.”

The trend is perhaps a natural consequence of the steady internationalisation of corporates domiciled in China. As KL Cheah, Head of J.P. Morgan Asset Management’s Global Liquidity Sales, Greater China explains, as the mainland has opened up, many Chinese companies have hired treasury personnel from other international markets. Exposed to new ways of thinking about short-term investments, these companies have begun look beyond deposits to think about the credit diversification benefits of MMFs, and developed their investment policies accordingly.

Resilient relationships

The question is whether the continued growth in interest asset managers expect to see in the MMFs in Asia will one day see the product become as well established as in the US and Europe. That will most likely depend on how a number of limiting factors play out over the coming years.

Firstly, relationship considerations may deter banks from encouraging their corporate clients to move non-operating cash balances off the balance sheet. There are cultural explanations for why this is the case. Large balance sheets continue to be a focus for many local banks in APAC; indeed, some Chinese bank managers are even compensated on the basis of balance sheet size. Moreover, with the enduring popularity of informal banking groups such as keiretsu and chaebol, in countries like Japan and Korea it is not uncommon for a bank to form part of a conglomerate’s core operations.

“There continue to be very close relationships between banks and corporates in APAC,” says Shevlin, adding that cross-selling opportunities might make non-operational deposits an acceptable trade-off for some banks. “Banks can offer multiple services and some may use deposits as a loss leader as a way to get in and sell those services. That relationship will only change slowly.”

Chart 1: Chinese MMFs are gaining importance in global market

Source: ICI, Wind, Fitch

Secondly, MMFs are far from being the only short-term investment alternative to bank deposits. In China, for example, commercial banks frequently introduce new products such as structured deposits – which can allow corporate investors to obtain yields significantly higher than either bank deposits or MMFs. While Shevlin warns that treasurers’ approach to these products should be firmly based on the caveat emptor (buyer beware) principle, he admits some clients might be tempted. “We are seeing a range of new products beyond MMFs, some of which have yields that are optically very attractive to clients,” he says. “But it is important for clients to understand the genuine risk and returns of these products – I think some of the attractiveness of these vehicles may fade as clients become more aware of the risks.”

A final limiting factor is APAC’s highly heterogeneous regulatory and market environment. Just how attractive an MMF product is to any given corporate investor may depend on the jurisdiction of the fund. Cheah makes the point, for example, that an institutional investor in Taiwan might be discouraged by the requirement to report any investments made; which includes MMFs above $10m, to the regulator. Chinese institutional investors for example will also face difficulty in freely accessing offshore investment options unless they have special approvals or investment quotas like the QDII. Enormous interest rate disparities also exist between markets, which undoubtedly influences the relative attractiveness of MMFs over bank deposits. “There are different restrictions affecting MMFs across markets in APAC, and differences in terms of rates,” he says, “and this does have an impact on the popularity and availability of MMFs in those different jurisdictions.”

Taking all these factors into consideration, there would appear to be a strong likelihood that any shift away from bank deposits to MMFs will not be an especially rapid one. But gradual though it may be, asset managers are convinced that Basel III will drive cash balances out of bank accounts and alternative investment vehicles like MMFs will be the main beneficiaries. Increasingly, they say, treasurers of locally domiciled companies in countries like China are learning to appreciate the level of diversification MMFs can provide for their short-term investments, and the added flexibility they give them to manage cash more efficiently across the businesses. And at a time when companies have so much cash on the balance sheet, having other investment options cannot be a bad thing.

“I think we will see clients adding MMFs as another tool in their toolbox,” adds Shevlin. “There is still a huge opportunity, to educate the market and to attract a whole new breed of clients that wouldn’t have considered MMFs before. Treasurers are not going to switch completely to something else, but they will surely want an additional option.”

MMFs: Things to consider

For a corporate treasurer looking to invest in MMFs in Asia, HSBC’s Bourke says there are a number of factors that should be kept in mind.

As noted earlier, the region’s industry is incredibly diverse. But differences in MMF products across jurisdictions may not always be reflected clearly in the ratings. “Depending on the currency of the fund the absolute level of credit risk can be very different between different currency options within Asia,” says Bourke. “So whilst a money market fund in India may have ‘AAA’ rating, that money market fund rating is for the India market, and the absolute level of credit risk is very different to a fund with ‘AAA’ money market fund rating in Europe for example. Investors should understand the norms in each market – from credit risk, to cut-off times, to settlement cycles: each market has its own characteristics.”

One should also be conscious that because asset managers manage their funds relative to local regulation, products may differ from what a US or European corporate might be used to in its domestic market. “Many multinational companies will look to invest with providers that they use or work with in another jurisdiction,” says Bourke. “So it is important to understand how that asset manager manages its investments for MMFs in different regulatory environments, as well as the governance around those products. Different structures employed in different jurisdictions, and the level of oversight is different between providers.”

But irrespective of these differences, Bourke believes the value proposition for corporate investors remains consistent across the globe. “The benefits MMFs bring to institutional investors do not differ between different domiciles,” he says. “Most of the features, in terms of credit diversification, portfolio management, and a high degree of liquidity and transparency are the same whatever the market. We expect clients to continue to see value in those features and continue to use MMFS and as we ramp up resources focused on Asia, we expect to see commensurate growth in AUM across the region as well.” HSBC Asset Management’s Bourke agrees, adding that he expects this broadening of the client base to drive further increases in AUM for HSBC’s China funds over the coming years. “In the past it has principally been US and European multinationals, but I think that is beginning to change. We are now beginning to see interest from China domiciled corporates as well and because of that we are confident we will be able to continue to grow our funds in the way that we run them today.”