Global green bond issuance topped US$200bn last year. But with demand far exceeding supply, and in a world where corporate social responsibility (CSR) is high up on many company agendas, what is holding green bonds back from reaching their full potential?

Green bonds are the most prized possession of the green finance industry – proven to be a key financial instrument which enables billions of dollars to flow into sustainable infrastructure across the globe.

Since the first green bond was issued by the World Bank in November 2008, the market has grown exponentially. Over US$200bn in green bonds was issued last year, up from US$170bn in 2018, and demand is far outstripping supply.

But what exactly is a green bond, and what makes it ‘green’?

Back to basics

Essentially, a green bond is a fixed-income instrument where proceeds or revenue streams connected to the bond are allocated for investment in new and existing ‘green projects’ which have environmental benefits.

More formally, the International Capital Market Association (ICMA) states green bonds are any type of bond instrument where the proceeds will be exclusively applied to finance or re-finance projects with clear environmental benefits and which are aligned with the four core components of the Green Bond Principles (GBP).

The ICMA’s GBP are effectively voluntary process guidelines that recommend transparency and disclosure, and promote integrity in the development of the green bond market by clarifying the approach for any issuance. The GBP provides issuers with guidance on the key components involved in launching a credible green bond.

There are four core principles:

- Use of proceeds.

- Process of project evaluation and selection.

- Management of proceeds.

- Reporting.

Whilst all four are required for the characterisation of a green bond, the crucial element is the green project itself.

Furthermore, for a green project to be eligible, it should have an environmental objective, such as climate change mitigation, environmental conservation or pollution prevention. Green projects could also incorporate eco-efficient products, green buildings, biodiversity, conservation or clean transportation.

Market movers

However, there remains a problem – namely that the lack of a universally-accepted global framework poses a risk to investors. Different market participants have different ways of quantifying sustainability, and different jurisdictions also have different regulations.

To take an example, the Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI) database includes green bonds, but the criteria it users differs from those used by the GBP principles. It has also been known to reject some green bonds from its database, despite the bonds meeting the GBP and gaining approval from third-party reviewers. Some areas of the CBI’s Climate Bonds Taxonomy, which “aims to encourage and be an important resource for common green definitions across global markets”, have made some green bonds issued in China ineligible and excluded from the CBI’s database.

However, despite the lack of universal regulation in the sector, demand for green bonds has skyrocketed over the past 12 years across a wide range of sectors, including natural resources (oil and gas, renewable energy, mining and metals and chemicals), and transportation (airlines, shipping and automotives).

In October 2019, stock market operator Euronext, which operates in Amsterdam, Brussels, Dublin, Lisbon, London, Oslo and Paris, launched its three-year strategic plan, ‘Let’s Grow Together 2022’. In doing so, the group has put sustainability right at its heart, stating that it wants to strengthen its green bond offering and existing environmental, social and governance market indices.

With more than 44,000 bonds, Euronext is one of the world’s global leaders for bond listings, with approximately €118bn worth of green bonds listed on Euronext markets – €40bn of which was raised in the last 12 months. In order to be eligible for inclusion, all green bonds must be aligned with a recognisable industry standard such as ICMA’s GBP or CBI taxonomies, and must be accompanied by an appropriate external review performed by an independent third party.

October also saw the London Stock Exchange (LSE), which lists more than 200 green bonds since it opened up its green bond segment in 2015, create a new issuer-level section for bonds by issuers whose core business activity is aligned with the green economy. This development enables eligible green economy businesses with more than 90% green revenues to admit bonds to the sustainable bond market (SBM). The LSE also launched the Green Economy Mark, which recognises equity issuers with green revenues of 50% or more.

“We continue to see growing investor demand for actionable climate related financial information, with global asset allocations to green and sustainable finance increasing each year,” says Nikhil Rathi, Head of the LSE, in a press release. “The launch of the Sustainable Bond Market and the Green Economy Mark underlines our commitment to finding innovative solutions to support issuers and investors in the transition to a greener economy.”

Being seen to be green

There are numerous reasons for this uptick in demand for green bonds and the response from the industry. Firstly, it goes without saying that the green bond label carries with it certain benefits, as in today’s climate ‘being seen to be green’ is high up on many companies’ agendas.

Environmental, social and governance (ESG) and/or socially responsible investors (SRI) have become buzzwords in recent years. And having green credentials, such as sustainability and the lowering of the business’s carbon footprint, plays well when it comes to attracting investment.

It’s a view held by Laurie Chesne, Green and Sustainable Assets Originator at French investment bank Natixis. “We carry out regular reviews and surveys in terms of ESG/SRI market intelligence, and this year we found that in Europe, around 50% of investors have really implemented SRI strategies within their investment strategy, and more than 60% of asset management in France is now performed in full ESG integration, which is pretty impressive compared to ten-15 years ago,” she says. “Whatever the sector – even in the high intensive industries – the interest in including sustainability as part of the business agenda is there and here to stay.”

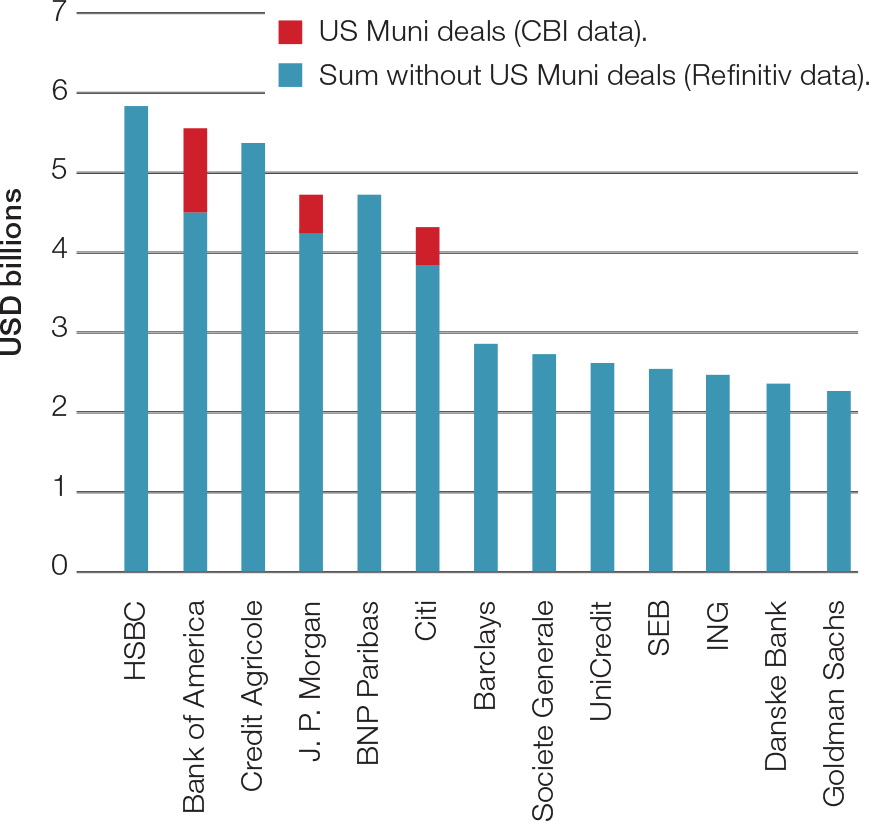

1H19: HSBC at No. 1 of global green bond underwriter league table

Source: Bloomberg – Global league table for corporate and government green bonds

The Nordic charge

Sweden is leading the charge when it comes to the issuance of green bonds. Data from the CBI found that the country issued a massive US$8.26bn in green bonds last year, the equivalent to about half of the total issuance across the Nordic region. That’s considerably more than Norway (US$3bn), Finland (US$2.6bn), Denmark (US$2.4bn) and Iceland (US$115m).

A prime example as to why Sweden is the forerunner in the region is the Swedish bank SBAB. Back in 2015, the bank started offering green investment loans to corporate and tenant owner association clients.

With SBAB’s experience of the property market, in January 2019 the bank became the first institution in Sweden to issue a green covered bond, backed by residential mortgages and property loans. This issue totaled SEK6bn (US$6.2bn) and with demand outweighing supply, it was quickly oversubscribed.

So, as part of SBAB’s ambition to be a recurring issuer in the market for green bonds, six months later the bank then became the first institution in Sweden to issue a green senior non-preferred bond, which amounted to SEK3bn (US$3.1bn) and will mature in June 2024. Once again, demand far outweighed supply.

Axel Wallin, Head of Sustainability at SBAB, explains why the bank chose to venture into the green bond market in the first place. “Sustainability is integrated in our business targets and goals and is imperative for our future competitiveness and success,” he says. “Hence, energy efficiency and other green investments have to be integrated into all of our product offerings.”

According to Wallin, buildings account for almost 40% of all energy consumption in Sweden, so there is a great need for drastically reduced climate impact from housing. As such, developing green products like green bonds not only leads to new business opportunities, it also lowers both risk and credit loss.

“Our green bond issuances are part of a sustainable transition of the Swedish housing and real estate market,” Wallin says. “When the entire value chain becomes green, all the way from green mortgage loan taker to investor, the green demand from investors can actively push the housing market towards sustainability.”

He continues: “We see a strong and increasing trend in the demand for sustainable investments from existing and new investors, and being able to supply the market with sustainable or green bonds not only helps us meet that demand but also helps us diversify our investor base.”

Moving forward

Moving into 2020 and beyond, a key focus for SBAB is to continue to be the lead player in the Nordic green bond market. “Our aim is to continue to be a regular green bond issuer,” says Wallin. The bank is also currently looking at adding a resilience perspective to the categories too. “We can address physical climate related risks and create incentives for customers who invest in extra drainage, water pumps etc and this might also decrease risk for investors.”

Investment bank Natixis is also blazing a trail when it comes to the climate and sustainability agenda. “We have two key values at Natixis when it comes to sustainability, innovation and integrity,” explains Chesne. “As a cross-asset Green and Sustainable hub, we explore the opportunity to include green or sustainability dimensions in all of our financial products offered, not just bonds or loans, when relevant.”

Back in September, and following 18 months of work, Natixis launched a Green Weighting Factor for its financing deals. This means that all of the bank’s transactions are given a rating colour. “Because we want to implement sustainability at the heart of our everyday business, all of our transactions are rated according to a seven scale of assessment – from dark green to dark brown,” says Chesne. “The idea is not to solely focus on a dark green approach, but really cover all of our clients’ profiles and support their transition towards greener activities.”

Despite the popularity of green bonds in the market, many significant challenges remain. These include complexity and cost, the lack of green contractual protection for investors, transparency, quality of reporting metrics and issuer confusion and fatigue.

This fatigue has come about because of the multiplicity of the criteria, the boundless and ever-increasing sets of rules, the overlapping roles of some market players, disclosure reporting guidelines and the standards that issuers have to adhere to. These include both the ICMA and CBI, but also ratings agencies, stock exchanges, index providers, certifiers, disclosure reporting guidance and second party reviewers.

It’s therefore hardly surprising that issuers are confused, especially in the EU, where the proposed EU Green Bond Standard is something of a moving target. Back in May 2018, the European Commission (EC) proposed legislation to tackle what it called ‘greenwashing’, where banks and other companies claimed their investments were environmentally sound. Now the EC wants to go even further and decide, once and for all, what is and what is not ‘sustainable’.

“With credible and ambitious definitions for sustainable investment, the EU will lead the world in sustainable finance,” said Bas Eickhout, a Green Lawmaker at the EU.

Arguing the case for issuance

Emily Weng, green bond specialist in BlackRock’s fixed income group, explains further: “Standardisation is definitely at the heart of increasing investor confidence and acceptance of green bonds. Many green bonds follow the voluntary ICMA guidelines in structure, but with varying standards in the current market, there are sometimes problematic cases of what issuers identify as qualifying projects, more fondly referred to as ‘greenwashing’, that can be confusing for investors.”

Regulation in defining what does and does not qualify as a green bond is therefore essential. Weng sees the EU taxonomy proposal and the efforts towards conformity of different green bond standards as good forward momentum. “Increasing transparency from issuers will also help,” says Weng.

“Green bond investors are pushing both issuers and fund managers to publish environmental impact reports, highlight best practices and encourage greater transparency in the market. We want to see this market grow and we want to see new issuers joining – but when they do, we want to see them come to market with good green bond projects that will actually result in defensible positive environmental impact.”

Whatever the sector – even in the high intensive industries – the interest in including sustainability as part of the business agenda is there and here to stay.

Laurie Chesne, Green and Sustainable Assets Originator, Natixis

It is a sentiment echoed by Chesne at Natixis: “The market is clearly growing year after year, and I think it will continue to grow,” says Chesne. “One of the major concerns however, remains standardisation and the lack of a common language. Clearly at the European level the market is evolving really fast and should the new EU Taxonomy and EU Green Bond Standard proposed by the Technical Expert Group come to pass, it will really help even more issuers identify the green assets that they have and frame their green bond structuration.”

An increasing amount of institutional investors however, do have well-defined and established green and sustainable investment guidelines. Chesne believes this will convince some new issuers to enter the market as they see more and more benefits, as well as economic benefits on the investor basis diversification and more indirectly on the pricing. We start to see some pricing benefits, not only in the secondary market but in the primary market too, especially for repeat issuers.

Industry bodies, as well as investor action groups such as Climate Action 100+, also have a role to play in driving the green market forward. Large market investors, including pension funds and sovereign wealth funds, are in a prime position too.

When all is said and done, the weight of demand for green bonds from institutional investors is only going to rise. As such, mindsets across the board will need to change accordingly – from politicians to regulators, and even corporates. Governments offering preferential rates or subsidies to issuers of green bonds is one development that could help. Should this happen, it will only attract more and more companies to issue green bonds and reap the rewards.

However, the most pressing need in the green bond arena moving forward isn’t just about having more issuers coming into the market – there also need to be enough bankable green projects to invest in, particularly when it comes to emerging markets. It is therefore vital that the whole financial system comes together to make the green bond market flourish.