Amid all the talk of disruption, disintermediation and ‘dumb pipes’, the imminent demise of the traditional bank – and its relationship with corporate treasurers – have been greatly exaggerated.

Amara’s Law states that the effect of a technology tends to be overestimated in the short run and underestimated in the long run. Advocates of open banking will certainly hope this is the case, since there is little evidence to date that APIs and non-bank competition have made a significant impact on treasury departments.

Fintechs have gained traction among companies with straightforward operating models where their cash account is in a single country. However, they have struggled to win business from multinationals.

“Cheaper cross-border transactions are obviously appealing, but even the largest fintechs have a pretty basic business model that is not sophisticated enough to deal with complex corporate treasury requirements,” says Eric Li, Head of Transaction Banking at business intelligence provider Coalition.

There is of course the possibility that consolidation could eventually lead to the emergence of large scale fintechs with the resources to develop sophisticated treasury products. But, Li suggests that fintechs will continue to struggle to take business off incumbents in areas such as supply chain finance, which can be a major overhead for companies making large numbers of payments to suppliers and customers.

Open banking should make the market more competitive as banks allow third parties to explore alternative products and costings. Yet the involvement of third parties adds another layer to the relationship with the bank and creates issues around governance, data privacy and security. Although the concept of a third-party intermediary may be helpful, safeguards and KYC rules need to reflect the role of the third party and whether there would be a conflict in recommending other bank’s products. If the objective is to open the market then this should drive down costs, but the reality is that this commoditisation comes at a cost of losing the relationship with one particular bank.

That is the view of Len Jones, a chartered accountant who has worked at senior finance levels in a number of businesses. He warns that banks will have to adapt their existing processes to cope with third-party systems and that open banking does not mean open season on data. “Banks’ systems need to be able to respond quicker and be scalable, otherwise we get into a race to the bottom with compromises on service standards – assuming that banks are able to invest in back end systems that will enable access to data,” he says.

Banks face technology challenge

Jones suggests that banks will have to significantly invest in their existing IT systems to enable them to be a market leader in service, and expresses doubt as to whether they can keep up with the pace of technological change necessary to provide real time information across multiple platforms. “We have already seen a number of disasters with bank IT initiatives and customers being denied access to their accounts,” he continues. “The biggest obstacle to banking innovation is the trade-off between the cost of upgrading legacy systems and the pace of change brought on by fintechs.”

While the UK has been the most enthusiastic proponent of open banking, similar initiatives are being explored in a number of countries including Australia, Canada, India, Japan, Mexico, New Zealand, Nigeria, Singapore and the US.

However, the regulatory impetus behind open banking is not the same across the world. In Europe it has been driven by regulators, whereas in Asia regulators have yet to commit to mandating open banking, despite encouraging the banking sector to move in that direction.

There are also nuances in relation to demand. “If we look at the oil and gas sector, there has been a focus on cost savings and improvements in recent years through reducing the cost of payments and liquidity management across subsidiaries,” explains Sen Ganesh, Partner at management consulting firm Bain & Company. “For other corporates, interest in open banking may be motivated by growth factors and the need to work with multiple currencies.”

The disparity in the pace of open banking implementation has implications for corporates with operations across multiple continents. For example, a treasurer with significant European operations might be looking at leveraging the new payment service providers, whereas in Asia that treasurer would still be reliant on the incumbent banks.

According to Ganesh, if a corporate takes the view that all the banks it works with will be operating in an open banking environment, it would have to invest in a set of APIs and set aside at least six months to get to the point where it is able to plug into the banks.

Treasurers adopt conservative approach

Then there is the challenge of whom to work with – most of the fintechs in this space are relatively immature and unproven, so would a corporate trust them to manage half a billion dollars of liquidity? In this context, many corporate treasurers could be expected to adopt a conservative, ‘wait and see’ position.

Ganesh is also unconvinced that multinational companies might be tempted to shift treasury centres from countries where open banking hasn’t gained traction to locations like the UK where it has been heavily promoted. “Services are often co-ordinated and executed in different locations,” he explains. “A corporate could establish a treasury centre in the UK from which it could co-ordinate its European payments, but for local payments in Asia it would still be necessary to send instructions to a local bank.”

Few local banks in Asia – with some exceptions such as DBS in Singapore, which has published some APIs – believe that open banking will be mandated in the near future.

Another barrier to wider adoption of open banking is that there is currently no ‘API standard’, so corporates have to create multiple APIs for similar solutions. API standards, services and geographic scope differ substantially between banks, which impedes interoperability and creates inefficiency and risk. In essence, each new API requires a lot of implementation work for corporates and licensed third-party providers.

A report released by the Open Data Institute in July noted that the UK’s Open Banking Implementation Entity plans to create ‘premium’ APIs that will sit above the mandatory regulatory APIs, and are expected to provide a commercial incentive for banks to grow the open banking ecosystem and improve the performance of their APIs. These premium APIs would be offered by banks under contract to third-party providers and could be paid for by those providers.

There are other initiatives to improve standardisation, such as the API Standardisation Industry Group founded by NACHA, the non-profit membership association charged with overseeing the automated clearing house (ACH) system. “Partnerships between banks, fintechs and infrastructure providers are a precondition for successful standardisation initiatives and these initiatives offer platforms for such collaboration,” says Job Wolters, Director Corporate Clients at treasury consultancy, Zanders. “It is difficult to say how many years it will take for us to arrive at a truly global, standardised set of APIs for corporate banking requirements, although the good news is that we are moving into the right direction.”

PSD2 and UK open banking regulations do not require banks to offer APIs for corporate accounts, although many banks supply these APIs for market-driven, competitive reasons.

Despite the challenges outlined, there is support for the view that API-enabled platforms and ecosystems represent the future of business banking. Non-banks and fintechs have long sold solutions such as treasury management systems, FX brokerage, accounts payable and receivable automation, and supply chain finance directly to corporate treasurers. Connecting to open banking portals via APIs offers the prospect of easier integration with real-time information and transactions. “We are seeing disruptors such as OakNorth Bank and Tide signing up substantial numbers of small and medium-sized enterprises,” notes Benjamin Ensor, a Research Director who covers the banking sector for Forrester. “While the absolute number of customers these firms have won won’t worry many large established banks, the speed at which credible competitors have not only entered the market but started winning customers should worry them.”

Independent of open banking, there are significant cost pressures on transactional activities and corporates’ expectations of enriched data are already high and growing, so it is necessary to capture very specific information to secure a mandate. Therefore, banks are experiencing some of the impacts of open banking even where it has not been implemented.

In the middle of this decade the financial media was awash with analysts debating whether banks would become ‘dumb pipes’ as their services were unbundled. However, the technology budgets that the largest banks have at their disposal are in some cases many multiples of the turnover of the fintechs trying to win business from them, and leave them well placed to grasp the opportunity to become orchestrators of services.

McKinsey describes ecosystems as an attractive play for any service business that can claim ownership of the primary customer relationship. Those entities that have the strongest relationship with the customer enjoy the highest profit margins in ecosystems and thus the most sustainable and lucrative business model. It would be hard to find any bank that would admit to being resigned to a reduced future role in the financial services landscape where it does no more than process payments. Those that fail to adapt risk becoming relegated to the role of capital provider and transaction processor.

These are not unimportant roles and banks with scale will continue to profit from providing such services. However, banks that don’t transform their operations risk losing their advisory relationship with corporate customers who will migrate to providers able to meet their needs faster and more efficiently.

Open banking has already improved access to information and markets, helping corporates get better pricing for banking products and services says Sankar Krishnan, Executive VP of Banking at consulting services provider, Capgemini.

Accelerating digital development

“The world’s top banks have a problem with legacy costs of operations and technology,” he adds. “With APIs, they are able to change the direction of their operations and technology strategy and enable digital transformation at a more rapid pace.”

Digital business ecosystems should provide access to better, faster and cheaper business services that are easier to integrate with other business systems – such as CRM – delivering operational efficiencies for many larger companies. In this scenario, Ensor believes treasurers, CFOs and their teams will spend less time trying to understand their current positions and cash flows, releasing more time to focus on optimising financial decisions.

Aite Group Senior Analyst, Enrico Camerinelli, says banks can improve their prospects of becoming orchestrators of services if they join forces to create platforms that become marketplaces for banking services empowered by standardised and common APIs. An example of this approach is the Nordic API Gateway, a data sharing utility supported by DNB and Danske Bank that provides unified API access to both personal and business accounts from all Nordic banks.

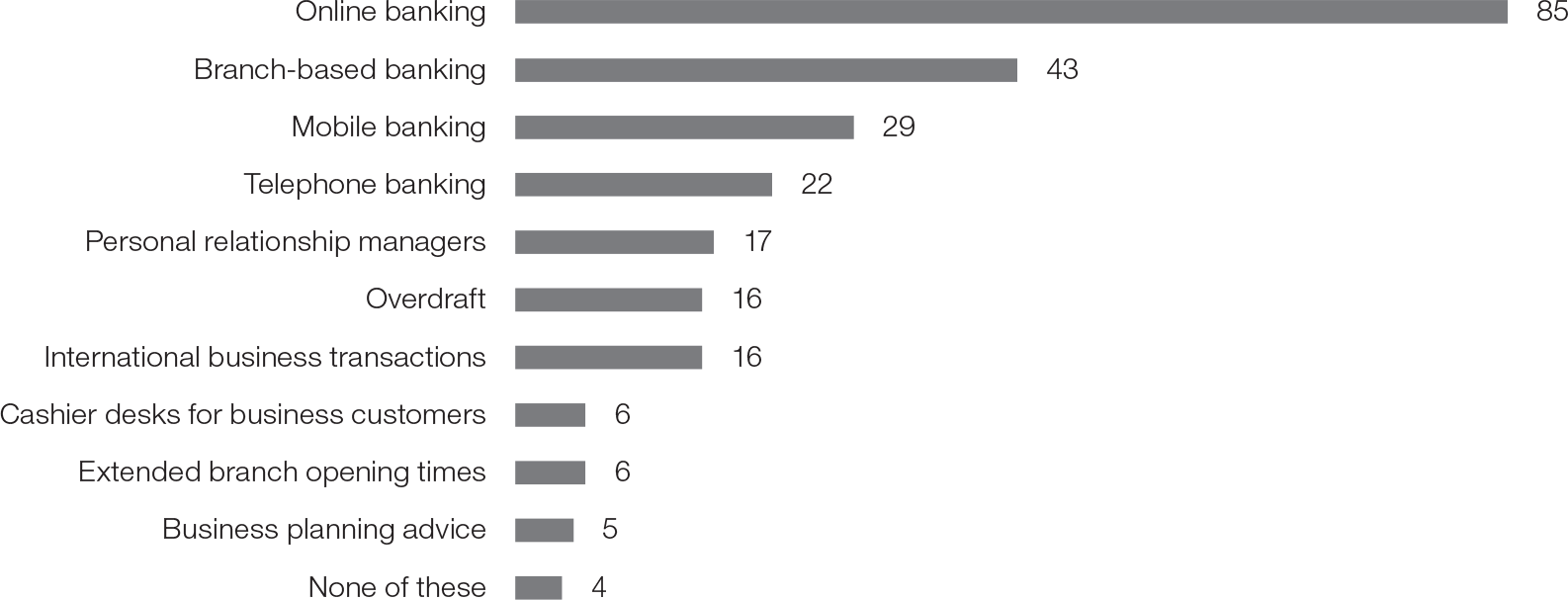

Chart 1: Financial services used by SMEs in the last three months for business purposes (%), 2017

Source: EY, The Future of SME banking report, December 2018

Lending platforms are one element of the financial ecosystem that is rapidly expanding, although they have a number of limitations compared with conventional bank borrowing. For example, while both banks and lending platforms perform a screening function by acquiring information to facilitate the decision of whether or not to lend, only banks engage in post-lending monitoring of borrowers. This manifests itself in the different kinds of contracts that banks and lending platforms offer. Bank loans are overwhelmingly secured by collateral, while loans extended by lending platforms are usually unsecured.

The main implication is that banks and lending platforms cater for different kinds of borrowers, observes Dr Sonny Biswas, Lecturer in Finance at University of Bristol. “Banks will probably keep lending to safer borrowers who can put up collateral to secure their loans, while the lending platforms will make loans to riskier and more innovative firms.”

There will be greater transparency on pricing for deposits and loans and this will help treasurers optimise across multiple banks, but that is just one part of the corporate treasurer’s relationship with their bank. Long-term financing is crucial and having long-term secured funding or working capital financing is likely to be of more importance than a reduction in some of the day-to-day costs associated with payments. Ganesh notes that banks are still far and away the largest provider of capital to companies, particularly those who are not large enough to issue their own bonds. Banks also provide advisory services to corporate treasurers on how to optimise their working capital and even set up treasury centres.

The power of relationships

Further good news for banks is that corporates continue to value their relationship. A November 2018 report on SME banking published by EY found that 43% of small-to-medium sized businesses had used their branch in their past three months (compared with 29% that had used mobile banking) and 17% had interacted with the relationship manager over the same period.

Corporates still value the stability and security of solid banking relations, particularly when it comes to keeping cash on deposit to provide for funding and processing transactions. This trust factor differentiates corporate banking from consumer banking, where the fintech revolution has proceeded much more rapidly.

The stability of a supplier, and support and development of solutions are of key importance for corporate treasuries, says Wolters. “A bank provides stability and security and is therefore generally considered a more reliable technology partner than a fintech. By teaming up with fintechs, banks have the possibility to offer their clients technology solutions beyond traditional basic cash management services. This is expected to be supportive to maintaining and growing the corporate client relationship.”

Patricia Hines, Head of Corporate Banking at financial services technology advisory firm Celent, is also unconvinced that we are moving towards a future where corporate treasurers and Chief Finance Officers conduct all their banking business virtually.

“The primary purchase decision by a treasurer is whether a bank offers its corporation credit lines and facilities,” she says. “Credit granting currently requires a lot of traditional interaction as the lender gathers the information required to make a credit decision.”

Stephen Lane, Finance Director of mechanical engineering firm Xtrac, says he likes to know that the company’s relationship manager understands the business and wouldn’t welcome a future where corporate treasurers and CFOs conduct all their banking business virtually. “I want to be able to sit down and talk to a relationship manager across a table about what is happening in our business,” he concludes.